By Berry Craig

NKyTribune columnist

Matt Bevin, the first Republican elected governor since Ernie Fletcher in 2003, doubtless hopes his fate will be different from “One Term Ern’s.”

A hiring scandal led to Fletcher’s defeat in 2007.

“At least a mob didn’t attack the governor’s mansion when Fletcher was in,” said John Robertson, a Paducah historian and author. “One did when Ruby Laffoon was governor.”

Laffoon, a Madisonville Democrat, riled just about everybody in Kentucky when he proposed a sales tax during the Great Depression, the worst economic calamity in American history.

Even many Democrats disowned him.

The Louisville Courier-Journal lambasted Laffoon in editorials. The embattled governor slammed the state’s largest paper as “Public Enemy No.1,” according to A New History of Kentucky by Lowell H. Harrison and James C. Klotter.

Former Gov. Edwin P. Morrow, a Republican, reviled Laffoon as “the Terrible Turk from Madisonville.” The nickname stuck.

Laffoon doggedly defended the tax. State revenues were plummeting when he took office in 1931. “He wanted to balance the budget and thought the tax was a good start,” said Robertson, who taught history at West Kentucky Community and Technical College in Paducah for many years.

So in 1932, to help refill state coffers, Laffoon urged the General Assembly to approve the sales tax. “This will be the most popular law passed this session,” he predicted.

The tax would have fallen hardest on poor Kentuckians, many of them jobless and with little or no savings. Merchants also opposed it as a sales killer.

On March 3, 1932, thousands of anti-tax store owners rallied in the rain on the Capitol lawn in Frankfort.

About 100 men and women did more than verbally abuse Laffoon’s levy. They raided the governor’s mansion, scaring the staff, trashing the floors and slightly damaging some furnishings, according to the Associated Press, which flashed the news nationwide.

Nobody got hurt, the wire service reported. Laffoon was in the Capitol building; the rest of his family was away, too.

Laffoon condemned the attack as “a disgrace and an outrage.” But he decided not to press charges and “preferred to let the incident drop,” the AP explained.

The storekeepers also disavowed the assault. They promised it wasn’t “part of their program of protest.” Even so, many in the mob sported “badges such as were worn to identify members of the protesting delegation,” said doorman Douglas Majors.

Majors also said one of the protestors offered him $40 to reveal where Laffoon was hiding. They suspected he had secreted himself somewhere in the mansion.

At any rate, the mob shoved past Majors and demanded to see “the women folks,” presumably meaning the governor’s wife and two daughters. Laffoon’s two grandchildren, ages 2 1/2 and 11, were home “but were not molested,” the wire service reported.

“This is not the governor’s house; it belongs to us because we paid the taxes for it,” the intruders announced. Majors said many of the marauders appeared to be drunk. They demanded “coffee but were told there was none prepared.”

The raiders spent an hour in the mansion, Majors said. One man purportedly packed a pistol, but didn’t pull it, the AP story also said.

Majors told the AP that the invaders “ate sandwiches they brought with them, played the piano and inspected most of the rooms on the ground floor.” They did not go upstairs, he added.

Laffoon claimed the uninvited guests “carelessly disposed of cigarette butts, burning holes in the carpet and searing furniture.” He also said they stole several light globes.

In any event, the legislature rejected the sales tax in 1932 and again in 1933. Yet Laffoon “more than doubled the whiskey levy and finally got his sales tax through in 1934, but inexplicably, he also reduced the real estate tax to one-sixth its previous level,” Harrison and Klotter wrote.

Nonetheless, “the state finally had achieved some fiscal stability,” according to the historians.

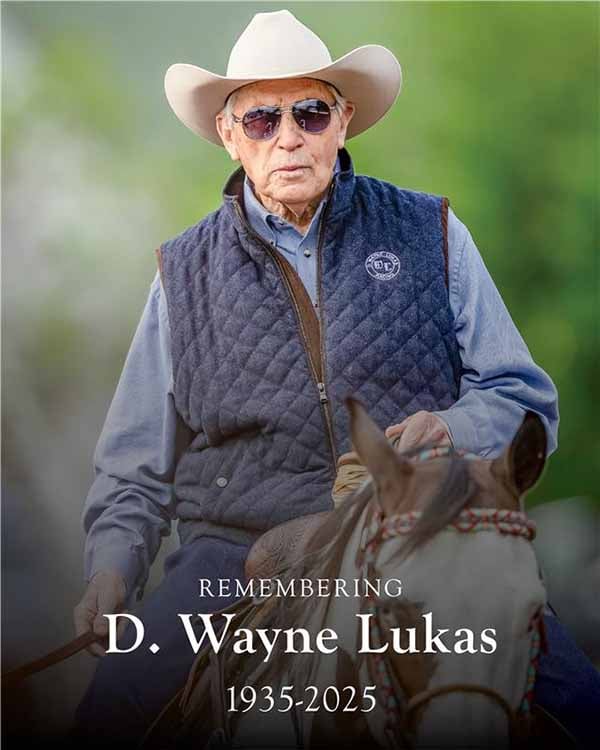

In 1935, Laffoon also made history for awarding a Kentucky Colonel’s commission to a chicken-frying Corbin restauranteur named Harland Sanders.

Otherwise, Laffoon ended up a sad figure, Harrison and Klotter wrote. The governor “lived in the mansion under guard to keep another mob away, went into a sanatorium to be treated for exhaustion, and then had to have surgery for appendicitis. In 1935 Laffoon left an office that had overwhelmed him.”

Laffoon died six years later and was buried in Madisonville, the Hopkins County seat, where he was born in 1869.

Even so, the “Terrible Turk’s” name lives on in Madisonville’s annual Gov. Ruby Laffoon-Gov. Steve Beshear Democratic dinner and, indirectly, in nearly 19,000 KFC restaurants around the world.

Berry Craig of Mayfield is a professor emeritus of history from West Kentucky Community and Technical College in Paducah and the author of five books on Kentucky history, including True Tales of Old-Time Kentucky Politics: Bombast, Bourbon and Burgoo and Kentucky Confederates: Secession, Civil War, and the Jackson Purchase. Reach him at bcraig8960@gmail.com