The following remarks were delivered to the annual Summit on Philanthropy held last week in Lexington. David Hawpe moderated a panel of experts addressing “What Kentucky Needs.”

Welcome to you all. The organizers of this conference have worked hard to assemble a truly high-powered panel of speakers. And the good news is, there’s no indication that Governor Bevin intends to replace any of them, or declare the whole panel dysfunctional and appoint a whole new one.

That’s good, because there’s no time to ask Judge Shepherd for an injunction.

At the 2014 philanthropy summit I was asked to name what I thought were the biggest challenges facing Kentucky. I chose six:

* a failure to dream big, except when it comes to basketball and bourbon;

* an underfunded state government that can’t meet the real needs and legitimate expectations of Kentuckians;

* a state health profile that keeps us at the top of the wrong lists;

* one coalfield region bogged down in cyclical poverty and economic decline so severe that it drains badly needed resources from other parts of the state;

* a yawning political and cultural chasm that separates Louisville from the rest of Kentucky; and

* a failure to fund at least one front-rank public university.

I could repeat those six this year because things things haven’t got much better. In fact, in some respects things are worse.

For example, more and more of state government is bogged down in the courts. We did take a giant step forward on health care when more than 400,000 Kentuckians got access to coverage in the Medicaid expansion. But Gov. Bevin has greeted that success with all the enthusiasm of a Baptist preacher welcoming a mouthy agnostic to a church picnic. In Eastern Kentucky the coal economy is disappearing, but the people of that region are lining up to vote enthusiastically for a presidential candidate who says he’ll bring coal jobs back. Those folks also believe each year’s UK football team will win eight games and go to a bowl. As for the city of Louisville, its hard-working mayor can’t persuade the rustic Republicans in the state senate to let Louisvillians vote themselves a local tax, to finance transformational change – a project-by-project, time-limited approach that’s supported by chambers of commerce from one end of Kentucky to the other. So much for conservative reliance on government closest to the people. South of downtown Louisville, on U of L’s campus, nobody knows who’s in charge. And the institution careens from scandal to scandal and crisis to crisis.

On the other hand, Kentucky has made some progress on infrastructure. If we get the kind of rain that flooded Louisiana, we have access to our own ark – a copy of Noah’s, parked just off Interstate-71. Admission is $40 per person, but maybe somebody at the ark park will follow the governor’s lead and let the poor earn their admission, by swabbing the decks. If they scrub hard enough they will have (as the governor likes to put it) “some skin in the game.”

The seventh dilemma

This year I’d like to add to my list of six challenges a seventh dilemma: the predicament of traditional media – especially those that used to cover state government most aggressively. We certainly get excellent individual journalism from Tom Loftus and Debbie Yetter at The Courier-Journal, Jack Brammer and John Cheves at The Herald-Leader, and of course Ronnie Ellis, the Energizer Bunny of the Frankfort press corps, who does an outstanding job for a group of community newspapers. Jamie Lucke deserves special mention for her editorial attention to Frankfort issues. KET is still doing its thing, and Louisville’s WDRB TV and WFPL radio (the latter with philanthropic help) have been juicing up their journalistic efforts. We’ve also seen the development of KyForward.com – a statewide online newspaper. But long gone are the days when The Courier-Journal, for example, maintained a five-person bureau in Frankfort and sent as many as ten people from Louisville to cover special legislative days.

It’s nobody’s fault. These days, media managers are doing the best they can with what they have, but so many have had their resources squeezed, their staffing trimmed, their mass audience quelched and their agendas distorted, by the demands and deadlines of the digisphere.

This all comes at a particularly unfortunate time.

How delicious it would have been, covering today’s Frankfort with enough people and enough time. That reminds me of the Happy Chandler story about the mosquito that flew over the fence into the nudist camp. It hardly knew where to begin.

The legendary Ed Prichard shared great political stories that I now use in speeches. One of those is relevant here.

Prich was sitting in John Y. Brown Jr.’s office while the then-governor fumed about yet another investigative scoop from the great Courier-Journal reporter Livingston Taylor, who was the scourge of both Democratic and Republican miscreants. John Y. Jr. raved and ranted, calling down retribution on the C-J in particular and journalistic wretches in general. His father, John Y. Sr., was sitting in the office too. Prich said the elder Brown let his son finish venting, and said, “Shoot, Johnny, if it hadn’t been for The Courier-Journal the SOBs would have stole everything but the Capitol dome.”

Of course it’s not just the investigative stories that matter. It’s day-to-day coverage that can educate readers, listeners and viewers about the way government is working – or not working. For example, do you know how Kentucky’s nationally embarrassing gay marriage license controversy was resolved? I doubt it. The media didn’t really tell you.

An (unfortunately) untold story

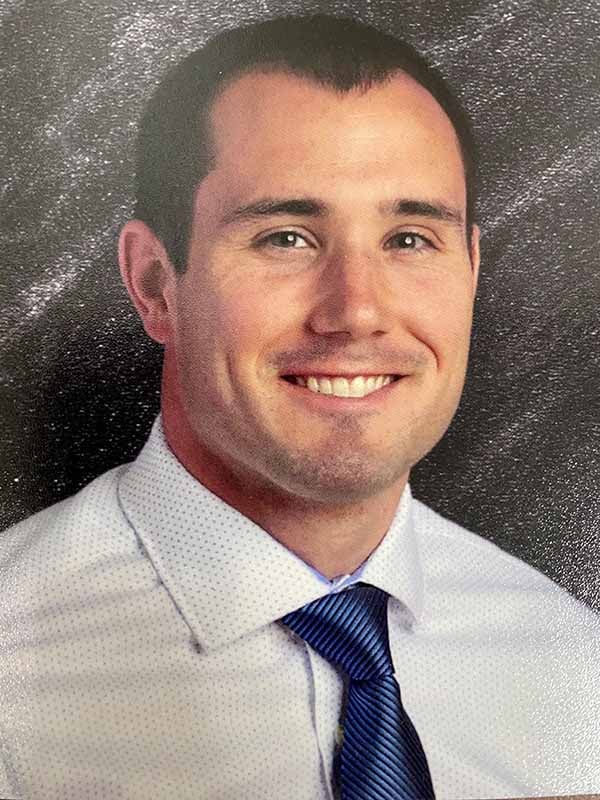

Earlier this year Morgan McGarvey – a first-term senator from Louisville, whom I help as his chief of staff – worked on a one-form compromise to end the national embarrassment of our Rowan County gay marriage license row. He argued that one form – with no requirement for the clerk’s signature and three describers from which an applicant could choose (bride, groom or spouse) – would be efficient, fair and defensible in those widely-anticipated lawsuits.

One memorable morning he made his case to a not-entirely-sympathetic crowd of 90-some clerks and deputy clerks in the big Transportation Cabinet auditorium, some of whom preferred to hand different license forms to gay and straight couples. They had questions, not all of them especially friendly.

Finally a woman stood up at the back of the room and allowed as how she had something to say because she had started all this. It was Kim Davis, the Rowan County clerk, who also allowed as how the young senator’s compromise was a good idea.

Morgan said I looked like I needed a defibrillator. I told him that in all the years I’ve known him – and I’ve known him since he was about six years old – that was the most bizarre 30 minutes we’d ever spent together. In the end, he was able to earn the clerks’ support for his one-form compromise. But the story didn’t end there.

I guess it was a few days later, as Morgan and I were driving from Frankfort to Louisville, that his cell phone rang. It was Matt Bevin on the line. After Morgan hung up he looked at me and grinned. He said, “You’re not going to believe this. The Governor wants to help me pass the marriage license thing.”

And that’s what he did. The conservative Republican governor worked with the progressive young Democrat from Louisville to get something done.

There’s more to the story, but what I’ve shared so far tells you that it would have made great news copy. But nobody was at the Transportation Cabinet auditorium that morning to cover the extraordinary event. Nobody probed for the back story that revealed a side of Matt Bevin seldom seen in political coverage. It was a nationally significant issue. It was good news. It reflected well on the Republican Governor and the Democratic senator.

It was something the public needed to know.

But you didn’t read it or see it or hear it.

Multiply that by all the other missed story opportunities and you get the measure of the media challenge. It’s something for philanthropies and philanthropists to think about.

As a former journalist I might be expected to see the media predicament as the seventh big challenge facing civic life in Kentucky. As those who channel the resources and creativity of philanthropy, you might see it as an opportunity.

David Hawpe is former editor of the Courier-Journal.