Part 2 of a continuing series on the 50th anniversary of one of America’s great watershed years, 1968.

By Paul A. Tenkotte

Special to the NKyTribune

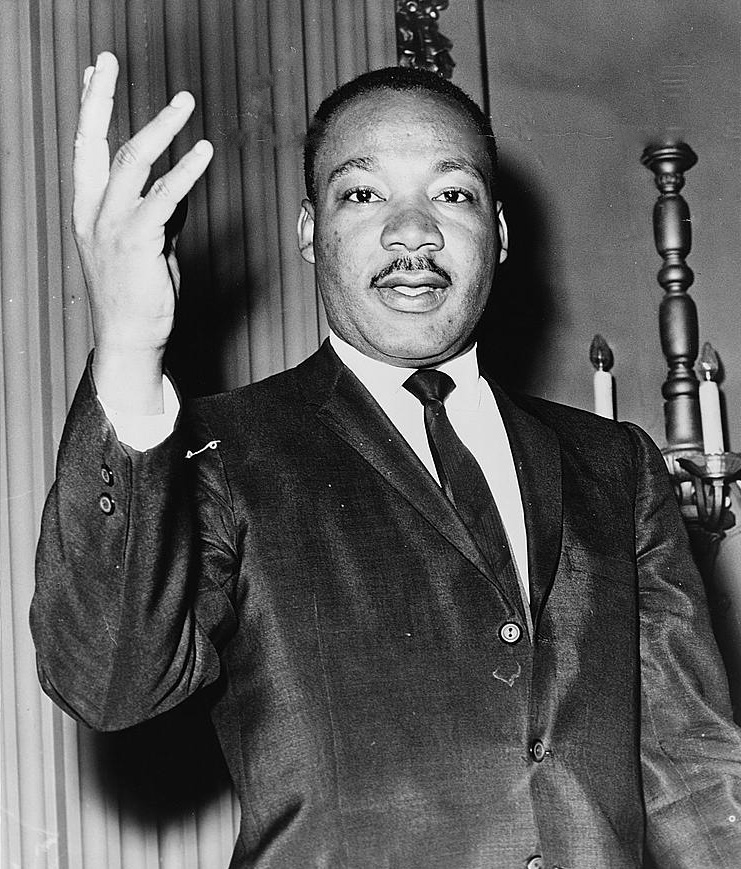

In last week’s column, we reviewed the life and Cincinnati connections of one of our nation’s greatest Civil Rights leaders, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. He was a courageous man committed to nonviolence, a visionary who strove for peace among all races, peoples, and nations.

Following King’s brutal assassination on the evening of April 4, 1968, in Memphis, Tennessee, many memorial services were held nationwide.

Sunday, April 7, 1968 was Palm Sunday, the beginning of Holy Week. President Lyndon Baines Johnson declared it an official day of mourning for Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. At 3:00 pm that day, over 1,000 people attended an interfaith memorial service for the slain leader at St. Peter in Chains Roman Catholic Cathedral in Downtown Cincinnati.

The principal speaker was King’s friend and colleague, Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, pastor of the New Light Baptist Church in Cincinnati. Others participating included: Archbishop Karl Alter of the Catholic Archdiocese of Cincinnati; Bishop Roger Blanchard of the Episcopal Diocese of Southern Ohio; Rev. L. Venchael Booth of Zion Baptist Church in Avondale (a friend of King); Rev. Otis Moss of Mt. Zion Baptist Church (a friend of the King family); Bishop W. J. Crumes of the Church of the Living God; Rev. M. J. Mangham of First New Shiloh Baptist Church; and Rabbi Albert Goldman of Isaac M. Wise Temple (Cincinnati Post, April 6, 1968, p. 2).

At the interfaith service, Rev. Shuttlesworth eloquently recalled the life of his friend. King, he said, “was accused by many of turning the world upside down, when actually he was turning it right side up.” Shuttlesworth declared that the God of love was trying to work through King, whose life was “a blueprint for living or a pattern for dying.” “God is not dead,” Shuttlesworth reassured the crowd. “The same God that King met still lives. He lives in me and in you” (Cincinnati Post, April 8, 1968, p. 6).

Meanwhile, Cincinnati Mayor, Eugene P. Ruehlmann, met with hundreds of civic leaders and called for “visible tangible evidence” of progress in race relations, especially in the areas of housing, employment and recreation. In addition, the City of Cincinnati closed its public schools for the week in memory of King (Cincinnati Post, April 8, 1968, pp. 1 and 6).

Sadness and anger, coupled by frustration over the lack of progress in ending racial segregation and discrimination, boiled over in riots nationwide. By Monday, April 8th, the Cincinnati Post reported that rioting had erupted in over 85 cities. Later that same evening, riots broke out in Cincinnati, killing two and injuring several.

Violence erupted in Avondale shortly after 6:00 p.m., as a neighborhood memorial service for King was concluding. Next, Mrs. Hattie Johnson, a 36-year-old black woman, was accidentally shot by her friend, who was protecting a store from looters. Rumors spread that she had been shot by a white policeman. Fire bombings and looting spread, quickly enveloping Avondale. By 7:00 p.m., the National Guard had been called. Later that evening, Hattie Johnson died.

The second fatality was Noel Wright, a 30-year-old white graduate student at the University of Cincinnati. He was dragged from his car at Dorchester and Auburn Avenues, and beaten and stabbed to death. Lois Wright, his wife, was also beaten, but survived. Black ministers denounced the violence and immediately established a reward to find Wright’s murderers.

The city declared an immediate curfew, and police arrested 220 people that evening. By early morning of the next day, the center of the riot, Rockdale and Reading Roads, lay in ruins. Lomark Drug Store, destroyed by fire in riots the summer before, had been set ablaze again. Segal Furniture Store on Reading Road was a complete loss (Cincinnati Post, April 9, 1968, p. 4).

Less than a year before, in mid-June 1967, riots rocked Avondale and many other neighborhoods of Cincinnati. It was called the “long hot summer of 1967,” as unrest swept across major American cities, especially Detroit. The Cincinnati riots flared up again a month later, in July 1967. Damage citywide was extensive. The Cincinnati Fire Department reported that between June 12th and July 25th alone, they had made 161 arson runs, with fires totaling over $2,160,000 in damages. Avondale suffered greatly from the riots of 1967 and 1968, never fully recovering.

I was only eight years old in 1968, but as I stated in last week’s column, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination shattered my innocent childhood world where adults were supposed to be rational leaders. Likewise, the Cincinnati and national riots of 1967 and 1968 flashed across the newspaper headlines and the television screen before my eyes. Adults around me were visibly shaken. My little friends repeated conversations that they had overhead from adults—people were buying guns to protect themselves, avoiding certain neighborhoods, essentially living in fear.

Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. understood fear, and its handmaiden, hatred. In fact, the evening before he was assassinated, in his great “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech in Memphis, King related that “And so I’m happy, tonight. I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man! Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord!”

We want to learn more about the history of your business, church, school, or organization in our region (Cincinnati and Northern Kentucky). If you would like to share your rich history with others, please contact the editor of “Our Rich History,” Paul A. Tenkotte, at tenkottep@nku.edu. Paul A. Tenkotte, PhD is Professor of History and Director of the Center for Public History at NKU.