The riverboat captain is a storyteller, and Captain Don Sanders will be sharing the stories of his long association with the river — from discovery to a way of love and life. The is a part of a long and continuing story.

By Capt. Don Sanders

Special to NKyTribune

In the late 1970’s, I acquired a plywood Weaver Skiff which once belonged to Captain John Beatty. I had more fun with that boat than any other except for the wooden Jon-boat of Walter Hoffmeier’s, the KIRK, and one carried aboard the Steamer AVALON which I rowed on every river we traveled upon, and that was a passel of waterways.

One time, I accidentally stuck the little AVALON jo-boat on the end of a steel pipe driven into Bear Creek, about a half mile above its mouth at Hannibal, Missouri; the same creek Sam Clemens swam in as a boy.

Captain Ernie Wagner was blowing the steamer’s thundering whistle to commence loading passengers, and it took nearly superhuman effort for a skinny seventeen-year-old kid to finally free the boat that was required, by law, to be aboard the AVALON as a rescue boat whenever the excursion boat was underway.

I thought I had gotten boat and baggage back aboard the steamboat without the Skipper realizing that one of his deckhands and the rescue boat nearly missed sailing. But later into the cruise, the big man made a point of rousting me from where I thought was safe hiding until the matter cooled. The Captain made me the recipient of a firm lecture of the type that earned him the nickname, “Stern Ern.”

The John Beatty Skiff became my property after I bought it from Dewey Puluso, a well-known riverman in the Cincinnati Harbor.

Dewey helped his sister Helen run the Newport Yacht Club, but several seasons before, he owned his own boat harbor with a headboat that looked like an old Army Engineers quarters boat painted government-fleet yellow. It had a leaky, wooden hull. On top, three decks up, “DEWEY’S” was spelled out in bright neon letters. Captain Wagner worked for Helen whenever he was laid-off for the winter, back when he was the First Mate on the excursion steamer ISLAND QUEEN.

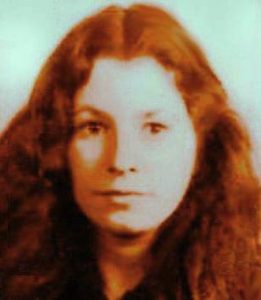

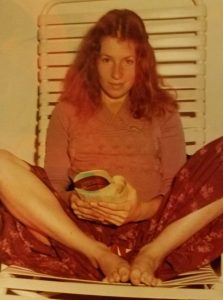

Of course, I paid Dewey too much for the broken-down skiff, but I wanted it bad enough to pay him his asking price. With the help of friends, I got that 500-pound wooden monster into an empty building and made sufficient repairs to render it riverworthy, and painted it a deep, barn-red with black and white trim. She was a beauty, and I named her the FLYIN’ FISH for my girlfriend, Deborah Anne Fischbeck, another beauty who once steered an open-decked sailing ship on a stormy, raging sea.

Eventually, Debra became a Mate on a tanker sailing across the Atlantic Ocean, through the Mediterranean Sea, and into the Black Sea carrying fuel oil to Soviet Union ports.

Debra was a maid on the Steamer MISSISSIPPI QUEEN and I was the First Mate when we met. Aboard the steamboat, she was usually called “Fish,” a name so perfectly attuned to all things maritime, that I often imagined her to be a character from Dante Alighieri’s The Divine Comedy: “She is Neptune’s daughter – For she’s drawn towards the water.”

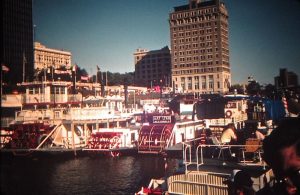

Fish steered, and I rowed the FLYIN’ FISH whenever she was off the MISSISSIPPI QUEEN, and we were together on our little wooden boat. During the late summer of 1979, our skiff was afloat on the Great Kanawha River at Charleston, West Virginia for the annual Sternwheel Regatta. All summer long I’d trained for the Skiff Races, “pulling” the heavy yawl upstream for miles against the strong current of the Ohio River from where the FLYIN’ FISH docked at the Mike Fink Floating Restaurant, across from the Cincinnati Public Landing.

Rarely did I rest while rowing for hours without missing a stroke of the oars.

Captain Clifford Dean of Red House, WV, a small town on the Kanawha River, taught me what he called the “Kanawha Crawl,” a method of rowing whereby the oars are feathered, but instead of lifting them from the water requiring additional energy, the blades, with a twist of the rower’s wrists, skim across the surface of the river.

The oarsman’s body then acts like a pendulum utilizing the rower’s weight to lighten the strenuous labor of rowing a heavy wooden boat making the task far easier than if sitting stiffly erect on the thwart lifting, feathering, pulling back through the air, and dipping the blades into the water again, for the next stroke. The “Crawl” required only the use of the boatman’s arms and shoulders and some back muscle thrown in for “English.”

Correctly done, the Kanawha Crawl made the rower into a human engine. The sounds of heavy, rhythmic breathing, coupled with the skimming hisses of the blades skipping across the water, made music not unlike the sounds of the Rees Variable-Cutoff Steam Engines I remembered from my happy days decking on the Steamer AVALON; later renamed the BELLE of LOUISVILLE.

Those venerated and reliable steam engines, whenever they are running on a full head of steam, the heavy metal “cutoff dogs” of those ancient machines, mechanical appurtenances that regulate the workings of the valves controlling the amount of flow of live steam into the cylinders, beat out their own melodies with their rhythmic clacking.

The Kanawha Crawl makes rowing a heavy, wooden yawl similar to engaging a steamboat into the “cutoff” position.

The pendulum motion of the oarsman’s body utilizes the inertia of his weight to do part of the work of the labor of rowing. During this rhythmic flow, the strain of exertion carried by the “rowing engine,” allows the human machinery a moment’s rest similar to the slight period of respite the heart has between beats.

Taken individually, those minute periods of relaxation appear insignificant, but taken as a whole over a long period of time, they allow the heart, the hardest working muscle in the human body, to outperform any mechanical pump ever invented. In much the same way, this “secret” style of rowing, perfected on the lower reaches of the West Virginia stream by an operator of hand-pulled ferryboats, enables a skilled performer to row cumbersome boats for hours; faster and farther than can an ordinary oarsman ignorant of the method.

The original intent of our plans to row in the Weaver Skiff Races on Labor Day Sunday changed after I received a call from home saying I was needed there on the day of the competition.

Fish and I were sitting aboard the FLYIN’ FISH slowly rowing around in the exciting maritime confusion that is the Kanawha River at Charleston during the Sternwheel Regatta. It was early afternoon, and we had to catch the Amtrak Cardinal train to Cincinnati later the next day.

Unexpectedly, I asked Fish if she would like to row up the river to Port Amherst, almost exactly five miles, to see if my former boss, Cappy Lawson Hamilton and his little paddlewheeler, MOMMA JEAN, were there. I was Lawson’s first Captain of his P. A. DENNY Sternwheeler excursion boat when it first came out three years earlier.

Nearly every small sternwheeler for hundreds of miles around was at the regatta, except for the MOMMA JEAN. Besides, I wanted to say, “hello” to Mr. Hamilton before we left, and what better river for a long row than the Kanawha above the Capital City?

Fish carried a man’s wristwatch with an unusually large dial stashed with all her other plunder inside her knapsack.

As we passed under the Southside Bridge, she took note of the time so that we could see how long it took to row to the Chuck Yeager Bridge at Port Amherst, five miles upstream from where all the boats and crowds were gathered. The Yeager Bridge at the busy river port below Malden, WV, an area made prosperous first by Malden Red Salt, and later by a low sulfur coal mined by generations of families living and working along Campbell’s Creek that entered the Kanawha not far below the finish line of the FLYIN’ FISH’s run up the river.

The trip on the Kanawha began from the Southside Bridge, the one connecting downtown Charleston to South Charleston, was the bridge Chuck Yeager was “alleged” to have flown under in an Air Force F-80 Shooting Star as hundreds of his fellow West Virginians crowded the bridge railings watching a boat race on the river below.

To protect their native son from disciplinary action for violating airspace rules concerning flying underneath crowded bridges, nothing official, not even in the Charleston newspapers, was ever reported detailing the high-spirited Mountaineer flyboy’s aviation hijinks. But it is the upper span crossing the Kanawha, five miles above, that proudly wore the name of the celebrated Air Force General, Charles Elwood “Chuck” Yeager, a native of Lincoln County, and the first human to fly faster than sound.

From Charleston to Campbell’s Creek, houses, various structures, and expressway roads crowd the riverbank. But riding deep within the gut of the river aboard a tiny ark built ages ago by Mr. Boone Weaver on the banks of the larger Ohio River at Racine, Ohio, the Kanawha seemed wild and picturesque-enough to please my flame-haired steerswoman who recorded a mental image of every detail that she might later recall if the need arose. Her attention to detail was reminiscent of our first trip on the Yazoo River at Vicksburg, Mississippi to examine the bones of the once, mightiest steam towboat on the river, the SPRAGUE, which at the time of our visit, was sadly a rusting, burned-out hulk.

The ride up the Kanawha rowed in no more than a steady, rhythmic pace without missing a stroke of the ashen oars, allowed only the barest conversation to pass between oarsman and steersman. Soon, the Yeager Bridge passed overhead, and Fish, who held the oversized watch in one hand and the steering oar in the other, called out the time:

“One-hour and thirty-five minutes!”

Not bad, I thought… a pretty fast run upstream against a light current. Later, I calculated that the FLYIN’ FISH completed the five-mile run upstream against the flow of the Grand Kanawha River averaging 3.16 mph.

The Port Amherst fleet, just above the Yeager Bridge, is mainly coal barges. Frequently, a towboat, or two, belonging to Amherst may be found either working the fleet or tied up. The regular boats, the IRON DUKE and the J. S. LEWIS, were absent. Both were five miles below and engaged in the celebration of the end of summer. The Amherst fleet also boasted of two unusual boats rarely seen on any river in this age: stern paddlewheelers, once working craft, but now, loafing about like retired thoroughbred racehorses

The LAURA J is the “Queen”of the Amherst armada and the pride of Captain Charles T. Jones, owner of both the boat and Amherst Industries, at that time, the largest family-owned company in the state. The MOMMA JEAN, once a Kanawha River ferryboat, lay tied below a coal tipple where Fish and I saw that someone was aboard. We coasted alongside as I called out:

“Anybody home?”

A man appeared on deck wearing glasses with thick “coke bottle” lenses, and in a deep, gravelly voice answered,

“Cappy, is that you? You’re just in time to help me decorate the MOMMA JEAN.”

Without hesitation, Fish fell to the task of hanging bunting, streamers, and flags with the usual enthusiasm she had for any job nautical; no matter how hard, painful or grungy it was, for she was an authentic “boatman” who understood the routine necessary to keep any vessel orderly, clean, and safe. Between trips, aboard the MISSISSIPPI QUEEN, I remembered her “turning over,” not only her rooms but also the rooms of one, even two, others girls who paid her so they could get time ashore.

Fish had that magnificent mane of brilliant, auburn hair tied back with a couple of strands of hair she pulled up from her head and tied into a knot that freed her face of frazzled locks during the frenzy wrought as she worked. Fish kept two porters running, dripping in sweat, keeping her supplied with sheets, towels, and the other necessities needed as she made her rooms ready for another gaggle of passengers soon to begin the best vacation of their lives.

Deborah was capable of supervising the MISSISSIPPI QUEEN’s kitchen, which she did when called upon during the absence of the regular Kitchen Manager. She was offered the position several times when it became available, but she always refused, fearing such time-consuming responsibilities would interfere with her free time she enjoyed sitting on the staircase on the starboard side of the Main Deck reading and watching the river scenery.

Soon the MOMMA JEAN was decorated in flags and red, white, and blue bunting, Mr. Hamilton’s favorite colors.

It seemed that everything Cappy owned was painted those colors: the MOMMA, the P. A. DENNY excursion boat, his Jet Ranger helicopter, his King Air turboprop airplane; even his trucks, bulldozers, and fuel oil tanks of his mining operations all boasted the same colors as the nation’s flag. But as we sat down to rest after all the industry of decorating his small paddlewheeler, Lawson apologized that he had nothing refreshing aboard to drink. He said if we wanted something cold, he would send for it at his Hansford office, many miles and mountain tops away.

“Wanna ride the chopper?” he asked with a huge grin, nearly stretching from ear to ear.

Fish and I excitedly climbed into the Jet Ranger, and his pilot took us to the office just minutes by air, but a couple of hours away of hard driving by road. The rotary-winged aircraft set down in front of the office displaying a sign in front identifying the place as the headquarters of Pratt Mining and Ford Coal. The pilot ran inside and returned with some refreshments and another passenger. The four of us were soon up and over several mountain ridges and back, all too soon, at Port Amherst.

Back aboard the MOMMA JEAN, we enjoyed a “cool one,” and as we talked, I mentioned to Lawson that we rowed up the river in one hour and thirty-five minutes.

“Why, Cappy,” he exclaimed, as all Captains of boats of note are addressed on the Great Kanawha River, and I had been the first skipper of Mr. Hamilton’s excursion boat, the P. A. DENNY, Sternwheeler.

“Cappy,” he continued, “You just beat my 1941 speed record by five minutes! I rowed the same course in ‘41,” he continued, “in one hour and forty minutes.”

My coxswain and I exchanged glances but said nothing. I looked for a twinkle in my former boss’s eye but found none. He appeared quite sincere. Lawson Hamilton was a man much like Captain Ernest E. Wagner. Both men could perpetuate the grandest practical jokes while maintaining an air of the most incontestable decorum. When in doubt about the seriousness of such men, it is always prudent to take them at their word without hesitation, for if there are unknown qualities involved, then they will reveal them, themselves, at their leisure.

The late afternoon sun was poised just over the top of the mountain high above the left bank of the Kanawha River, so I mentioned to the Fish that we had to be going as it was getting dark soon, and we carried no light on the FLYIN’ FISH. We bid our host farewell, and as we stepped down into the Racine skiff, Lawson said, almost matter-of-factly:

“You beat my time of an hour and forty minutes up the river, but I rowed back down in fifty-five minutes.”

We pushed off, and neither Fish nor I knew if Lawson had challenged us, or if the man, so powerful in these mountains, was just “funing” us and not expecting us to take him seriously. We knew, however, we had to decide if Mr. Hamilton was joshing or engaging us.

So we pulled under some overhanging trees halfway between the Amherst fleet and the Yeager Bridge to discuss the last puzzling comment Cappy Hamilton let slip as we stepped into our boat. Perhaps he thought that we understood he was only making up the story, but still, Lawson threw down the gauntlet, real or imagined, and I felt he wanted us to take up the challenge to beat his 1941 downbound speed record from Port Amherst to the city front – bridge-to-bridge.

“Do you think we should try?” I asked Fish.

“Go for it!” answered the river girl who never wasted a word.

The oars were made ready and the Fish, looking at the oversized watch, quietly whispered,

“Now…”

With Fish’s one spoken word, we accepted the challenge to beat Lawson Hamilton’s unbroken thirty-eight-year-old speed record on the downbound leg. The oars bowed with the first strokes as they bent to the entire weight of crew and wooden boat. The sun dipped behind the high mountain crest opposite Campbell’s Creek as we slid by unnoticed by a constant stream of automobiles and diesel trucks hurtling past on the roadway above. Fish instinctively kept the boat in the channel to take advantage of what little current there was in the river.

The momentum of the Kanawha Crawl method of rowing propelled the heavy boat forward in a steady, rhythmic gait as noticeable white rollers formed in our wake upon the water as we rolled into the deep, cool shadows beneath the high limestone cliffs near the Daniel Boone Park.

These cliffs were formed by man’s hand for the expressway that lay at the base of the bare bluffs. Dark seams of black coal ran horizontally at different intervals on the sheer stone walls.

But, I never saw them that trip, for I had transformed myself into a human engine onboard the FLYIN’ FISH fueled by the shared mastery of the rower’s art perfected by an oarsman of long ago who discovered an ideal way to row a skiff for hours-on-end with the least amount of energy expended. I may have said a silent, “Thank You,” to Captain Clifford Dean, but if I did, it was a subliminal reaction I was not aware of at the time.

Below the Dan’l Boone park we passed the wooden pilings driven into the riverbank by Captain Harry White so that the LAURA J and the MOMMA JEAN could land there at their owners’ favorite restaurant located on-shore, where they enjoyed taking their guests for what was considered by many, “the best food” served on that stretch of the Kanawha River.

A few minutes more, and we were abeam of the Blackhawk Light and Dayboard, a government navigation aid maintained by the Coast Guard. The Kanawha City Bridge was ahead, about halfway to the finish line. As we descended closer to the celebration below, the number of boats increased.

Above, the river was quiet except for a couple of fishermen heading upstream for some night fishing in the rapid water below Marmet Lock and Dam. But now, fast motorboats swept in close to witness the curious sight of the antiquated red skiff roaring down the middle of the river propelled by a madman rocking back and forth to the violent stroking of the hissing oars. At the stern thwart sat a vision that few would forget; a real-life Mer’girl with both arms wrapped around a long steering oar keeping the boat running true; a long cigarette hanging lightly between her lips..

“There’s a lot of boats down there,” Fish observed while she stared ahead into the dimness below as twilight spread its dark cloak over the river.

“Whatt’a we going to do for a light?” she asked, never breaking her stare of the river ahead.

At the Kanawha City Bridge, Fish checked her watch and reported that twenty-seven minutes had passed. Because the river was beginning to broadened-out the farther we went, and the current slacking, I expected the FLYIN’ FISH to slow down as we came nearer to the Sternwheel Regatta congregation. We had to have more power, so I rowed even harder.

We passed close to the steps that ran into the water below the West Virginia State Capitol Building. Lovers looked up from smothering embraces and watched as we raced by. The closer we got to our goal, the darker and more crowded the river became.

As the minutes crept by, it was still possible to break Mr. Hamilton’s 1941 record, but more speed was needed. We were about a half-mile from the South Side Bridge, our goal, which was clearly in sight. The boats and barges anchored below partially blocked the river from the right-hand shore to nearly halfway to the left.

A thousand motorboats raced around like mayflies on the Mississippi. With what remaining reserve of energy I could muster, I began a sprint to the finish line; pumping the last of what was left of me into the “Kanawha Crawl” as the stout, wooden boat raced toward the beckoning bridge. The outcome of the race was so uncertain that we could not predict if victory was ours, or if Mr. Hamilton’s 1941 speed record would remain undisturbed.

But the fact remained, the FLYIN’ FISH and crew still had a chance to become the new rowing champions of the Great Kanawha River.

A small parade of supportive well-wishers followed us although the river was dark-enough for lights, still enough visibility remained that, in no time, were we, or any other boats, in danger of colliding. The Crawl worked me into a steaming lather as my “human engine” was full-stroking on a double gong.

Suddenly, a piercing, revolving blue light shattered the murky darkness of the race course!

“SHOW YOUR LIGHT – SHOW YOUR LIGHT!” an electric bullhorn boomed over the waters.

“SHOW YOUR LIGHT. THIS IS THE UNITED STATES COAST GUARD!”

Fish immediately looked my way. She was scared. But I remembered the government regulation concerning lights required aboard a vessel under oars that said something like: “Shall have ready at hand an electric torch or lighted lantern shining a white light which shall be exhibited in sufficient time to prevent collision. ” I Informed my steerswoman that as were almost to the finish line, I was not about to stop so close to our goal. We would never have another chance to break Lawson Hamilton’s 1941 record, so I instructed the Fish:

“Light that cigarette lighter!”

Fish looked at me like I was nuts, so I repeated my request:

“Go ahead, Fishie, FLICK YOUR BIC!” (I actually said it that way.)

Deborah kept her lighter in her shirt pocket, and reluctantly, she dug it out, held it up, and struck the flint. A white light shone all-around while the oars sang their song as they propelled us toward the bridge, just a few hundred feet away.

Instead of placating the United States Coast Guard, they became enraged when Fish flicked her Bic. The bullhorn demanded:

“STOP YOUR BOAT!”

By now, the guardsmen’s boat was just astern on our outboard side. I yelled back that I could not stop.

“I’m trying to break a 1941 speed record!” I shouted again, thinking that my explanation would make them understand why we were racing down the middle of the Kanawha River at night like demons, with no light aboard except a half-empty Bic cigarette lighter for a navigation light.

“STOP YOUR BOAT! STOP YOUR BOAT, OR WE’LL RAM YOU!” The bullhorn blasted in my face, not more than ten feet away.

“STOP, OR WE WILL RAM YOU!”

The Coast Guardsmen were reservists, “Weekend Warriors,” getting in their duty time toward retirement and a government pension. And their boat was not made to government specifications, one that could not stand up to giving a stoutly-built Weaver Skiff a solid ramming. The fiberglass boat’s blue lights were attached to the windscreen with threaded turnscrews about the size typically used to hold a net stretched taut across the width of a ping-pong table. A strip of gray adhesive tape helped reinforce the light brackets.

The threat of ramming was both funny and frightening, but I could see that the Fish was wishing she was cruising some moonlit stretch of the Lower Mississippi instead of where she was awaiting the fatal assault of a fiberglass runabout ramming across the FLYIN’ FISH’s midsection. As I realized the Coast Guard reservists were considering the consequences of their next step, fighting back a smile, I yelled over:

“Don’t ram us! Give us an escort to the bridge!”

Apparently, the Guardsmen considered that a reasonable request and they escorted us the rest of the way to where the echoes of river noises and human voices bouncing off the piers and understructure of the Southside Bridge seemed to make it come alive, like the roar of a football stadium, as we flashed under and “green-lighted” the central span.

“Time!” I yelled.

Fish gazed at her oversized, round watch dial and studied a moment before announcing:

“Fifty-three Minutes…”

“We Won! We Won! We beat Cappy Lawson Hamilton’s 1941 speed record of fifty-five minutes by two whole minutes! I shouted.

As I pulled in my oars and the FLYIN’ FISH took a lazy, fish-hook-shaped path and slowed down as the Coasties came alongside. One recognized me in the bright lights below the bridge from my P. A. DENNY days and ordered me to tie up the FLYIN’ FISH for the night and leave it there – which I gladly did.

Later that evening at a gathering on one of the sternwheelers, I saw the reservist who recognized me earlier, and I told him the story of the race to best Cappy Hamilton’s 1941 speed record. I promised to always carry a light, although I usually did. But, unfortunately the previous night, we were caught on the river without one.

I wanted to add that we had Fish’s Bic cigarette lighter, and believe me, I thought, if we’d been drifting down into the darkest gloom on the Lower Mississippi River with just that lighter and a thirty-barge tow was bearing down on us, we would be flicking that Bic. We would be rubbing two fireflies together, too, if that was all we had. But I kept that thought to myself.

The next afternoon, Fish and I boarded the Amtrak Cardinal, bound for Cincinnati.

Captain Don Sanders is a river man. He has been a riverboat captain with the Delta Queen Steamboat Company and with Rising Star Casino. He learned to fly an airplane before he learned to drive a “machine” and became a captain in the USAF. He is an adventurer, a historian and a storyteller. Now, he is a columnist for the NKyTribune and will share his stories of growing up in Covington and his stories of the river. Hang on for the ride — the river never looked so good.

Captain Don Sanders is a river man. He has been a riverboat captain with the Delta Queen Steamboat Company and with Rising Star Casino. He learned to fly an airplane before he learned to drive a “machine” and became a captain in the USAF. He is an adventurer, a historian and a storyteller. Now, he is a columnist for the NKyTribune and will share his stories of growing up in Covington and his stories of the river. Hang on for the ride — the river never looked so good.

Thrilling – I was right there with you and Fish!

Omg, thanks for sharing this! I too worked on the Mississippi Queen. This is a GREAT read! Brings back so many wonderful memories

Marvelous reading!!! Who needs tv when you have the words of Capt Don Sanders!! Love it!!!