Part 2 of our series, “Resilience and Renaissance: Newport, Kentucky, 1795-2020”

By Paul A. Tenkotte

Special to NKyTribune

Mountains, the Cumberland Narrows, and the Ohio River Valley

The Ohio River Valley, with Newport, Kentucky at nearly its halfway point, was an epicenter of a major global war that changed the course of British and American history. The lush lands of the Ohio River, however, lay beyond a major mountain barrier.

There is something mysterious about mountains. Unlike many of the large urban areas that humans inhabit, mountains are often sparsely populated. They seem to defy the attempt to tame them. Even when we succeed in traversing them with technology—whether tunneling or cutting our way through—mountains often fight back. Erosion, rock slides, and other phenomena demonstrate that nature is ultimately in charge.

Even the attempt to define the boundaries of mountains proves difficult. By comparison, a meandering and changing river seems almost stable. With mountains, however, where does a plateau end and a mountain begin?

The vast Appalachian Mountain chain in the United States and Canada generally lies along the Eastern Continental Divide. East of the Appalachian Mountains, water flows into streams and rivers that eventually empty in the Atlantic Ocean. West of the divide, waters feed a vast tributary system, including the Ohio River, flowing ultimately into the Gulf of Mexico.

Just as we often partition oceans into separate seas to help define location, so too mountain chains often bear distinct range names. One part of the Appalachian Mountain chain is the Allegheny Ridge, also called the Allegheny Front, or simply the Alleghenies. Stretching from Pennsylvania through Maryland, West Virginia, and Virginia, the Alleghenies at first were a barrier to Anglo-European settlement beyond.

All mountains have passes, however, allowing them to be crossed. Cumberland, the county seat of Allegany [sic] in Maryland, lies in such a valley pass. Situated at the junction of the North Branch of the Potomac River and Wills Creek, the city is the farthest navigable point west along the Potomac River. It was the home of the British colonial outpost, Fort Cumberland.

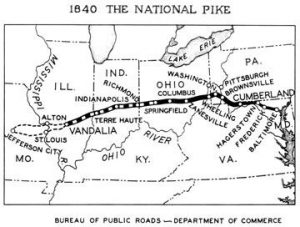

Nearby lies the Cumberland Narrows (not to be confused with the Cumberland Gap in southeastern Kentucky), through which American Indian, and early Anglo-European trails passed, including the British colonial war route, Braddock’s Road. Later, in the early 1800s, the National Road (also called the Cumberland Road) was constructed from Cumberland, Maryland, to Wheeling, West Virginia on the Ohio River, and beyond. The Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad, completed to Wheeling in 1853, also traversed the Cumberland Narrows. Meanwhile, the Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Canal from Washington, DC was finished to Cumberland in 1850.

Ninety-five years earlier, in 1755, British Major General Edward Braddock (1695–1755) left Fort Cumberland with his troops in an attack against the French at Fort Duquesne (now Pittsburgh). Called Braddock’s Defeat, it claimed his life and was a major loss for the British.

Braddock’s Defeat was part of the French and Indian War (1754-1763), as it was called in America. In 1754, warfare erupted in the American colonies between France and Great Britain, each concerned about the expansion of their imperial holdings west of the Allegheny chain of the Appalachian Mountains, in the vast and rich Ohio River Valley. The conflict evolved into a major world war called the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763). Fought around the globe, it pitted Great Britain, Prussia, Portugal and their allies against France, Spain, Austria, and their allies. These alliances were a result of one of the world’s most important foreign policy changes, the “Diplomatic Revolution of 1756.”

For the north German state of Prussia, the “Diplomatic Revolution of 1756” was a watershed in history, catapulting it into an important European power. In the earlier War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748), Great Britain and Austria had been allies, fighting against France and Prussia. The Treaty of Aix-la-chapelle (1748) ending that war allowed Prussia to retain Silesia, a rich province that it had seized from Austria and the mighty Habsburg family. Understandably, Austria was displeased with the results of its alliance with Great Britain.

Britain, in turn, saw the handwriting on the wall. Prussia was an up-and-coming power, vitally important to British interests in the northern German state of Hanover. This was profoundly significant, because in 1714, when the British Stuart dynasty came to an end, the British crown’s cousins in Hanover took over, inaugurating the Hanoverian dynasty. Thereafter, Great Britain and Hanover were ruled by the same dynasty. In 1756, Great Britain allied itself with Prussia, who promised to come to the aid of Hanover should the latter ever be invaded by France. In 1757, during the course of the Seven Years’ War, that exact scenario occurred.

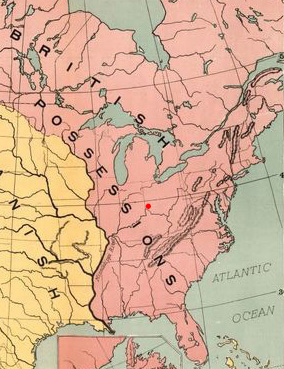

In February 1763, signatories to two separate treaties—Paris and Hubertusburg—officially ended the Seven Years’ War. Great Britain emerged as the world’s leading imperial nation. In the negotiations, France lost most of its North American possessions to Britain, including Canada, and everything east of the Mississippi River, with the exception of New Orleans. Further, Spain gave Florida to Britain. The results were especially important for the Ohio River Valley. Lying at about the halfway point of the Ohio River, what would later become the Cincinnati and Northern Kentucky region shifted from French to British ownership.

The American Revolutionary War

However, the meteoric rise of Great Britain and Prussia were not the only results of the negotiations of 1763. Ironically, Britain’s vast imperial gains in the Seven Years’ War would lead directly to the American Revolution. Facing the need to defend this immense new territory, the British Parliament began to levy new and heavier taxes on the American colonists. This, in turn, resulted in a movement for independence. Further, British King George III (ruled 1760-1820), feared that if American colonists rushed to settle the newly-won territory west of the Appalachians, it would upset Britain’s American Indian allies. So, George III announced the Royal Proclamation of 1763, temporarily restricting further settlement in the Ohio Valley region.

Of course, American colonists were upset with the Royal Proclamation of 1763. In a whole series of explorations and incidents, they began nicking away at the western territory and negotiating settlements with various Indian tribes. In 1768, for example, George III’s Indian commissioner had to step in, concluding the Treaty of Fort Stanwix that essentially established British claims to lands south of the Ohio River (including Northern Kentucky, across from what would become Cincinnati). And in 1774, by the treaty of Camp Charlotte ending Lord Dunmore’s War, the Shawnee Indians agreed to stay north of the Ohio River.

The American Revolution brought war to the Ohio River Valley. Major expeditions were launched from the Point, located at the confluence of the Licking River with the Ohio River in Kentucky. After the revolution, the new United States of America “gained title to the trans-Appalachian West, with the exception of British Canada, and the Spanish possessions of Florida, West Florida, and New Orleans.” (Tenkotte, Claypool, and Schroeder, Gateway City: Covington, Kentucky, 1815-2015, 3).

American Indians lose the Ohio River Valley

The post-Revolutionary period proved a disaster for the American Indians of the Ohio Valley and the Northwest Territory. The Indians, troubled by white incursion, and by the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, formed a massive confederacy of tribes to protect their territory north of the Ohio River. The Northwest Indian War initially led to major American defeats, including those of the Harmar Campaign (1790) and St. Clair’s Defeat (1791).

Nevertheless, the tide of war began to turn against the native tribes. In 1789, the federal government established Fort Washington in the new town of Cincinnati. By 1794, with the federal victory at the Battle of Fallen Timbers and the subsequent 1795 Treaty of Greenville (now Ohio), the Northwest Territory was finally considered safe for white settlement.

Anglo-European Settlement

Land speculators and pioneers realized that the tide against the Indians was turning years before the Treaty of Greenville. In 1788, the US Congress sold an immense tract of land in the Ohio Valley, between the Little Miami River to the east and the Great Miami River to the west, to John Cleves Symmes of New Jersey. Symmes had hoped to purchase two million acres, but unable to make the necessary payments, it was subsequently reduced to 311,682 acres.

In the same year, settlers established two towns in Symmes Purchase, Columbia west of the mouth of the Little Miami River, and Losantiville (later renamed Cincinnati) opposite the Licking River. In 1789, Symmes and a group of settlers founded a third village, North Bend, near the mouth of the Great Miami River.

Parts of this article formerly appeared in Tenkotte, Stevie, et al., Cincinnati, Ohio: Dynamic American River City (Cincinnati, OH: Stevie Publishing, 2019), as well as in Tenkotte, Paul A. Rival Cities to Suburbs: Covington and Newport, Kentucky, 1790-1890 (dissertation). Ann Arbor, MI: University Microfilms International, 1989.

We want to learn more about the history of your business, church, school, or organization in our region (Cincinnati, Northern Kentucky, and along the Ohio River). If you would like to share your rich history with others, please contact the editor of “Our Rich History,” Paul A. Tenkotte, at tenkottep@nku.edu. Paul A. Tenkotte, PhD is Professor of History at Northern Kentucky University (NKU) and the author of many books and articles.