Part 30 of our series, “Resilience and Renaissance: Newport Kentucky, 1795-2020″ and Part 1 of our series: Organizing for Action: Women’s Suffrage in Northern Kentucky”

By Paul A. Tenkotte

Special to NKy Tribune

Have you ever personally felt “boxed in”? That you had the intelligence, talents, skills, and ideas to contribute to society but were ignored? That you weren’t considered for a job or promotion because of your gender, race, ethnicity, or sexual orientation? If you have felt this way, then you are definitely not alone.

However, you probably learned that feeling and acting alone—in isolation—was not going to achieve anything positive. You had to stand arm-in-arm with others to fight for yours, or other people’s, rights. Such is always the case with attaining human rights. Ultimately, you have to organize for action.

The women of Northern Kentucky, especially of Covington and Newport, organized for action in crusading for women’s suffrage, that is, the right to vote. Like the national story of women’s rights, many of the early actions of women in Northern Kentucky were focused on the larger struggle against slavery.

White and black women alike of Northern Kentucky were involved in the antislavery movement before the Civil War. In January 1856, Margaret Garner and sixteen other enslaved people from Boone County “made their escape through Covington, Kentucky and across the frozen Ohio River to Cincinnati. There, slave capturers cornered them, but not before Margaret Garner reached for her two-and-a-half-year-old daughter Mary, and killed her with a butcher knife rather than see her return to slavery. For many people refusing to recognize the atrocities of slavery, the Margaret Garner case—and its resultant trial—forced them off the fence” (Tenkotte, “Our Rich History: Abolitionism and the Ohio River Valley, intersection points between free, slave states).

Caroline Ann Withnal Bailey (1813-1867) of Newport, Kentucky was an abolitionist seeking to abolish the evils of slavery. The wife of William Shreve Bailey (1806-1886), she assisted her husband in publishing The Free South, a Newport-based antislavery newspaper. Withnal “was born in Wheeling, in the Northern Panhandle of current West Virginia, an area known for its opposition to slavery” (Tenkotte, “Missing historical puzzle pieces and more information on abolitionist William Shreve Bailey,”). She was a courageous woman, facing enormous prejudices and violence. Angry mobs torched the Bailey home in 1851, and destroyed their presses in 1859. Like many women of the era, however, very little is known of Caroline Ann Withnal Bailey, other than she died in Covington, Kentucky in March 1867. There are no known surviving photographs of her.

How could such important women, including Withnal, disappear from history? Why have their stories only recently been recovered? The answer is clear. Then, as now, history was generally seen as marked by the deeds and accomplishments of men.

“In 1869-1870, during the presidency of Ohio-born Ulysses S. Grant, Cincinnati, Northern Kentucky and the nation watched and waited as the 15th Amendment to the United States Constitution worked its way through state legislatures for passage. Like all amendments, it would require that three-fourths of the states approve. Finally adopted in 1870, the 15th Amendment guaranteed that ‘The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude’ ” (Tenkotte, “Our Rich History: 150 years ago, politics and racism polarized Americans; the role of Sen. John Sherman,”)

To the great disappointment of the many who had worked for an end to slavery and for the full enfranchisement of emancipated peoples, the Fifteenth Amendment excluded women. The battle for a woman’s right to vote had to be renewed and reenergized, leading to a decades-long struggle called, alternatively, “woman suffrage” or “women’s suffrage.”

To depict the women’s suffrage movement as a monolith, with everyone agreeing on basic principles and strategies, would be a tremendous injustice to its complexities. Having experienced the disappointment of the finalized Fifteenth Amendment, many women realized that the fight ahead would be difficult, and would have to focus on realizable goals, incremental steps, and practical strategies. They knew that opponents would embrace cultural norms, biological frameworks, biblical passages, and socioeconomic arguments. So, women organized themselves to counter the fallacies of these arguments, and to formulate attainable goals and strategies.

On the other hand, a smaller group of women viewed the cultural, biological, religious, and socioeconomic norms of the day as the very nucleus of a larger problem of human inequality. In their view, the outdated structures of society needed to be scrapped and to be rebuilt anew.

In the end, the wide spectrum of goals and strategies were all significant to the successful achievement of women’s suffrage. Then, as now, different approaches enlivened and enriched the debate—a debate which underscored the fact that for democracy to flourish, organizing for action was at its heart.

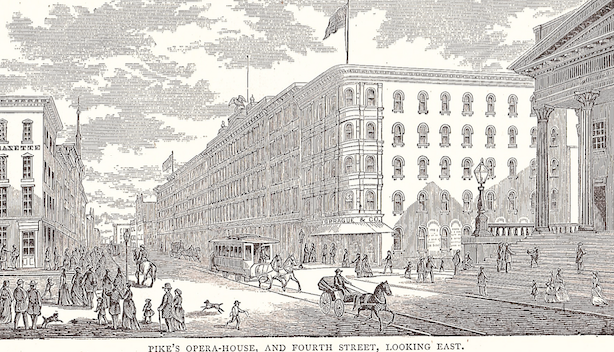

In January 1869, national women’s leader Lucy Stone visited Cincinnati, delivering a lecture entitled “Women’s Rights” at Pike’s Music Hall on Fourth Street. Stone claimed that the Declaration of Independence, as well as the Bill of Rights of the US Constitution, established that liberty was a self-evident right of all. The paternalistic argument often used by men—that women didn’t need to vote because the men in their lives, whether husbands, fathers, brothers, or sons, represented their interests—was simply untrue. Further, Stone argued that it was no surprise “almost without exception that a woman doing the same work is paid far less than a man. We need the vote that we may secure a fair compensation for our services” (“Mrs. Lucy Stone at Pike’s Hall. Her Lecture Last Night,” Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, January 27, 1869, p. 8).

About eleven months after Lucy Stone’s Cincinnati lecture, Wyoming Territory became the first place in the United States granting women, unconditionally, both the right to vote and to hold political office (Tenkotte, “Our Rich History: In 1869 Lucy Stone lectures in Cincinnati, refuting stereotypes of her day,”).

In the same year, 1869, two important organizations were established. National leaders Susan B. Anthony (1820-1906) and Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815-1902) “founded the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) in May 1869. The NWSA preferred to embrace a much wider platform of women’s rights, in addition to a constitutional amendment for women’s suffrage. On the other hand, Lucy Stone established the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) in November 1869. It pursued a more gradual approach to attaining women’s suffrage, focusing on the states themselves” (Tenkotte, “Our Rich History: In 1869 Lucy Stone lectures in Cincinnati, refuting stereotypes of her day,”).

The AWSA held its 11th Annual Meeting in Louisville, Kentucky in October 1881. Lucy Stone was serving as President of the AWSA, and worked closely with Mary Barr Clay (1839-1924), the eldest of four adult daughters of noted Kentucky abolitionist, Cassius Marcellus Clay (1810-1903) and suffragist Mary Jane Warfield Clay (1815-1900). In 1883, Mary Barr Clay became the first Kentucky woman to serve as the president of the AWSA. She, in turn, influenced her younger sister, Laura Clay (1849-1941), to become involved in women’s rights.

Consumed by other responsibilities, Laura Clay waited until 1888 to become actively involved in women’s rights. In January of that year, she co-founded the Fayette Equal Rights Association in Lexington, replacing a prior suffrage organization there. The new group differed from the earlier one in that it sought a greater range of rights for women. Indeed, its goals were “ ‘to advance the industrial, educational and legal rights of women, and to secure suffrage to them by appropriate State and National legislation’ ” (Paul E. Fuller, Laura Clay and the Woman’s Rights Movement. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1975, p. 31).

On October 22, 1888, Eugenia Farmer and Isabella Shepard established the Kenton County Equal Rights Association (KCERA) in Covington, the second equal rights association in the state. By 1889, its membership numbered twenty-four, and it had circulated a “Married Womans’ [sic] Property Rights Petition,” as well as run two candidates for “School Board Trustees” (Minutes of the Kentucky Equal Rights Association, November 19th, 20th, and 21st, 1889, Court House, Lexington, Kentucky, with Reports and Constitution. Lexington, KY: Will S. Marshall, Jr., Printer, 1890, p. 8).

In terms of property law, Kentucky and other states generally regarded married women as relinquishing their property to their husbands at the time of their marriage. Called coverture under English and American common law, it meant that married women could not own property, sign legal contracts, or earn an income that did not ultimately belong to their husbands. On the other hand, an unmarried woman, known legally as femme sole, generally exercised those rights.

KERA’s and KCERA’s efforts to reform married women’s rights proved successful. On March 5, 1890, the Kentucky General Assembly passed “An Act for the benefit of the married women in this Commonwealth.” This legislation expanded upon the rights of married women in Kentucky, as originally granted to them in an 1872 act of the General Assembly, which stated “That the wages and compensation of married women, for service and labor done and performed by them, shall be free from the debts and control of their husband; and their employers are allowed to pay such wages and compensation directly to such married women, and payment to them shall be a full discharge and acquittance of the employer” (“An Act for the benefit of married women in this Commonwealth,” Public Acts of the State of Kentucky. Frankfort, KY: S. I. M. Major, Public Printer, 1873, p. 36). The 1890 act removed the words in bold above and replaced them with “shall pay such wages and compensation to such married women only, unless otherwise directed by the written order of such married women” (Acts of the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Kentucky. Frankfort, KY: E. Polk Johnson, Public Printer, 1890 Vol. 1, pp. 23-24).

The School Board Trustees election pursued by KCERA in 1889 presumably related to a fairly esoteric and seldom-used section of an 1838 act of the Kentucky General Assembly. Regarded as one of the first pieces of legislation in the United States to grant women the right to vote in school board elections, section 37 of “An Act to establish a system of Common Schools in the State of Kentucky” (approved February 16, 1838) stated “That any widow or feme [sic] sole, over twenty-one years of age, residing and owning property subject to taxation for school purposes, according to the provisions of this act, in any school district, shall have the right to vote in person or by written proxy; and any infant residing and owning property, subject for taxation for school purposes, according to the provisions of this act, in any school district, shall have the right to vote by his or her guardian” (Acts of the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Kentucky, December Session, 1837. Frankfort, KY: S. G. Hodges, State Printer, 1838, p. 282).

That same 1838 law had probably been invoked in Dayton, Kentucky in January 1872, when women property owners of that small Ohio River city publicly voted in an election. Instead of voting by proxy, however, they had voted openly, some going “arm in arm with their husbands to the polls and while the husband voted one way, the wife, to show her ‘independence,’ voted the opposite way.” The editor of the Frankfort Yeoman, in an article reprinted in the Covington Journal, decried the move, citing an oft-repeated claim that women should “remain in the sacred, hallowed sphere of home, and the social circle, to which the wisdom of the highest civilization and her unerring instinctive tastes have assigned her, and to keep her as far away as possible from the infectious pollutions, the horrid contaminations that surround the hustings and envelope the ballot box. Carry out the views of the Women’s Rights agitators of this country, and then we may say farewell, a long farewell to the poetry of creation. After that, no more women in this country—nothing but a nation of big bearded men and vaunting Amazons” (“Women Voting in Kentucky,” Covington Journal, January 27, 1872, p. 1).

The AWSA held its national convention in Cincinnati in November 1888. Among the many attendees were Eugenia Farmer of Covington and Laura Clay of Lexington, Kentucky. Lucy Stone, who knew and had stayed at the home of Mary Jane Warfield Clay, invited Laura Clay to give a speech at Cincinnati. Inspired and emboldened by the Cincinnati convention, “delegates from Fayette and Kenton counties” crossed the Ohio River and founded the new Kentucky Equal Rights Association (KERA) on November 22, 1888” (Paul E. Fuller, p. 32).

KERA’s constitution clearly echoed the words of the Fayette ERA, “Its object shall be to advance the industrial, educational and equal rights of women, and to secure suffrage to them by appropriate State and National legislation.” (Minutes of KERA, 1889, pp. 39-40).

Next Week: Covington and Newport women emerge as state leaders of KERA.

We want to learn more about the history of your business, church, school, or organization in our region (Cincinnati, Northern Kentucky, and along the Ohio River). If you would like to share your rich history with others, please contact the editor of “Our Rich History,” Paul A. Tenkotte, at tenkottep@nku.edu. Paul A. Tenkotte, PhD is Professor of History at Northern Kentucky University (NKU) and the author of many books and articles.

Certainly appreciate all of the research and expert writing in this series so far. Thanks Paul!

The interplay of the slavery and women’s suffrage is a fascinating piece of our history. Thanks, Paul, for bringing this aspect of NKY history to light. It took over 70 years of protests, demonstrations, letters, lectures, and women’s time in prison to get the right to vote (Seneca Falls, NY convention in 1848 to ratification of the 19th Amendment 1920). Frederic Douglass reminded us in an 1857 lecture that “If there is no struggle there is no progress… Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.”

How dare you take our statues down. They are part our history. If all confederate statues come I want ALL STATUES COME DOWN I MEAN EVERYONE