By Pat Ryan

Special to NKyTribune

Part 9 of our series on the 75th anniversary of the closing stages of World War II and Part 42 of our series, “Resilience and Renaissance: Newport, Kentucky, 1795-2020.”

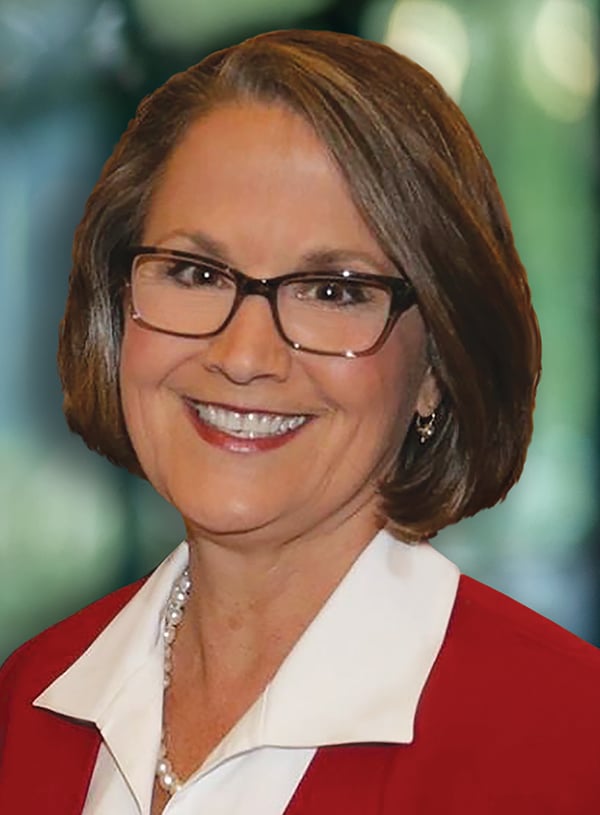

Each day, thousands of commuters and travelers drive along I-275, crossing over the Licking River between Campbell and Kenton Counties on the Alvin C. Poweleit Memorial Bridge. The bridge hails a World War II hero, who was a lifelong resident and renowned medical physician in Northern Kentucky.

Born on June 8, 1908, in Newport, Alvin Charles Poweleit lived most of his early years in various neighborhoods of Newport and vicinity. He was an adventurous little boy, enjoying swimming in the Licking River. In May 1916, his mother died.

His father, like many workingmen of his day, made temporary childcare arrangements until remarrying five years later and reuniting the family. In the interim, Alvin and his brother were sent to live in an orphanage, while Alvin’s sisters were placed with an aunt.

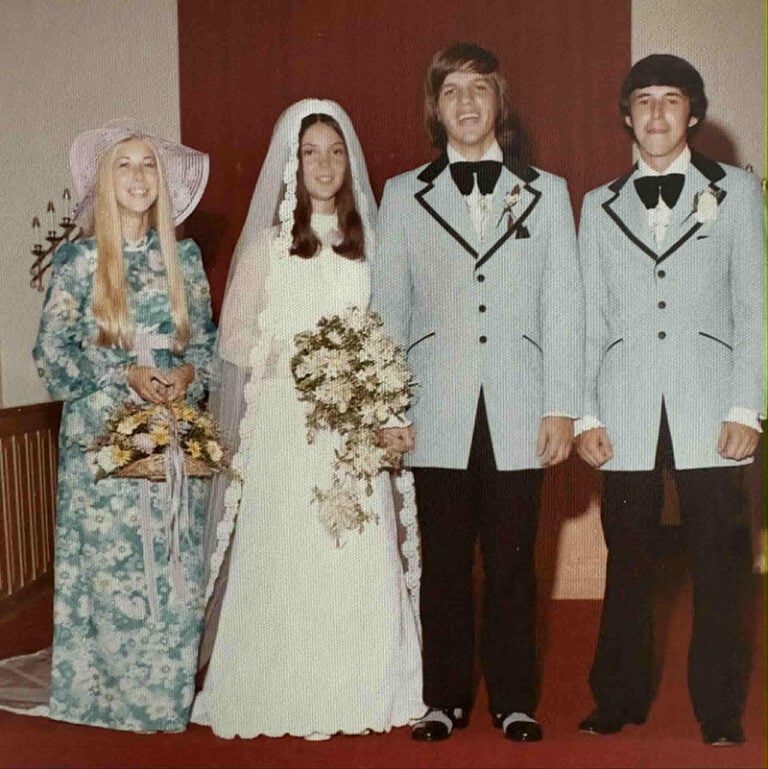

Poweleit was an excellent athlete, playing football at Newport High School. After graduation in 1926, he worked for a while to earn money to attend college. He entered the University of Kentucky (UK) in Fall 1927, where they promised him a job in exchange for trying out for the football team. He remained at UK for one year and then transferred to the University of Cincinnati (UC), to be nearer his girlfriend and future wife, Loretta Thesing.

Graduating from UC in 1932, Poweleit was accepted into several medical schools, but matriculated to the University of Louisville. He earned his MD degree there in 1936, and became a resident physician at St. Elizabeth Hospital in Covington. To supplement his salary, he also joined the US Army reserves. In 1940, he was called up to active duty.

When Poweleit arrived at Ft. Knox, as a member of the Army Medical Reserves in January of 1941, the world was in chaos. Hitler’s Nazi forces were overrunning Europe, Japan was expanding into China, and America wanted nothing to do with either. It did not take Poweleit long to figure out that the US military was ill-prepared. Using his great intuition, Poweleit took steps to do all he could to give himself the best chance to survive a potentially bleak situation.

First, he learned to operate every type of vehicle and shoot every type of weapon in the tank battalion. Second, thinking Asia would be his most likely destination, he bought books on the fauna and flora common in that area of the world (Poweleit, USAFFE, p. 7). Third, he hired a Japanese-American sailor to teach him Japanese as the battalion was being transported across the Pacific to the Philippines (Poweleit, USAFFE, p. 3).

Poweleit’s unit, the 192nd Tank Battalion, arrived at Fort Stotsenberg in Central Luzon, 60 miles northwest of Manila, on Thanksgiving Day, 1941. The very next day, after a chance meeting with Gen. Douglas MacArthur, Poweleit got to work scouting Luzon, the largest of the Philippines Islands for fresh water and plants that could be potentially converted into foods and medicines. Within a matter of days, Poweleit came to realize two key points. First, unlike his fellow soldiers, he believed the Japanese Imperial Army would be a well-disciplined, battle-hardened adversary. Second, the American military machine at that time was complacent, ill-trained and poorly supplied (Poweleit, USAFFE, p. 11).

Alvin Poweleit’s perceptions became reality on December 8, 1941. Ten hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the most improbable happened. USAFFE forces (United States Army Forces in the Far East) were caught off guard by a Japanese air assault on the Philippines, and like Pearl Harbor, its air defenses were destroyed in a matter of minutes (Drury & Clavin, p. 59).

Two weeks later, the Japanese launched a massive invasion on the Philippine island of Luzon. The 192nd Tank Battalion, (Lt. Poweleit was commander of the medical detachment), moved to the beaches of Lingayen Gulf to meet the assault.

By the end of the first day, USAFFE forces were in full retreat to the Bataan Peninsula where American and Filipino forces would make a gallant four-month stand until their food, medicine and munitions ran out. Lieutenant Poweleit would become one of the “Battling Bastards of Bataan” (Poem penned by Frank Hewlett, 1942; Norman & Norman, Tears in the Darkness, p. 128).

During the five months following Pearl Harbor, the battered American forces in the Philippines held out, hoping that the United States would come to their rescue. But help was not to come. Events in Europe and other parts of the Pacific were of higher priority.

Lt. Poweleit was in the thick of the war from the outset. With the opening salvo of Japanese bombs destroying Clark Air Field, he and his medical crew were administering first aid to severely injured servicemen. Later, he would be with the 192nd battling Japanese invasion forces providing aid to the wounded. A week later, Poweleit and three others would be engaged in a firefight. In the pitch darkness of night, his crew heard the cracking of a twig coming from a nearby creek. Poweleit identified it as a Japanese patrol of eight. They formulated a plan for each in their group to ambush and kill two of the enemy. The plan worked to perfection. Fearing the noise would attract attention, the Americans retreated from the area (Poweleit, USAFFE, p. 24).

By January 1942, USAFFE forces were pushed back into a defensive line on the Bataan Peninsula. Poweleit suffered his first of several wounds during the war. He was assigned to a medical station just behind the front lines and while hoping to find a few precious moments to rest, the station was hit by an air raid.

Jumping for cover with shells exploding all around him, a piece of shrapnel hit him in the chest, bounced off a rib and landed four or five inches below the point of entry. Poweleit did not go back to the safety of a hospital far behind the lines. Instead, he convinced a reluctant Filipino doctor at the scene to extract the two-inch piece of metal shrapnel from his chest.

Then, just before surrender, he was operating on a patient when the Japanese conducted a bombing raid on the main field hospital. Windows shattered and the ground shook. Poweleit threw himself over his patient and they both emerged alive but many around the hospital area did not. Debris was flying everywhere and a piece of metal shaving lodged in the socket of one of Poweleit’s eyes. He had it removed but it would bother him for a few days. Before it completely healed, USAFFE forces on Bataan surrendered. The date: Good Friday, April 9, 1942 (Poweleit, USAFFE, p. 43).

Official surrender to the Japanese Imperial Army was to begin in the early morning. From that day on and for the next three years, Poweleit and the American and Filipino captives would experience the full measure of retribution inspired by the “Bushido” code. A Japanese soldier, dating back to the “samurai” military tradition, would rather die fighting than dishonor himself, his family, and his country by surrendering to the enemy. Equally, he viewed an enemy who gave himself up as “cowards who deserved to be treated like animals for the dishonorable act of surrendering” (Miller, p. 25).

The Bataan Death March, as it would become known, began for most prisoners at the very southern tip of the Bataan Peninsula, in the vicinity of the town of Mariveles. The Japanese collected the capitulating prisoners, placed them in columns of four, and began the grueling process of walking the men a distance of 60 or more miles to a collection depot called Camp O’Donnell.

The captives, thousands in number and far more than the Japanese had planned for, were already sick, injured and starving. They would be forced to march, sometimes run, in the humid tropical heat for hours without water. Any attempts to leave the ranks to get water would be certain death. If a prisoner fell to the ground in exhaustion, he would be bayoneted or shot to death. If a prisoner stopped to help a fellow prisoner, he would be beaten or killed (Tenney, p. 48).

Atrocities perpetrated along the march by the Japanese were often random. A prisoner’s life could be snuffed out at the whim of a Japanese guard. The Japanese barbarity was meant to inflict psychological trauma as much as physical brutality (Norman, p.172). Poweleit had one of those harrowing experiences.

Along the march, Poweleit and a prisoner walking next to him were ordered out of line and taken behind a building. Waiting there were three Filipino prisoners and a host of guards. Without any reason, the guards, pulled their swords and without hesitation cut off the heads of the Filipinos. With alacrity, the guards turned to the two Americans; it was not their day to die. The guards led them back to the march (Poweleit, USAFFE, p. 52).

After six days of torturous marching, Poweleit’s column reached the rail lines at Capas at about 12 midnight. They were made to stand for three more hours before they were finally herded into the boxcars for a four-hour train ride to Camp O’Donnell. The men were jammed into the cars, all in a standing position. In each car, for those that died en route, there was no room to fall.

Some died from suffocation; some merely gave up. Poweleit again put his Japanese language skills to use. He managed to get a spot near the door and asked the guard to leave an open door space. The guard complied; a few lives were saved that night.

Camp O’Donnell was an abandoned Filipino training base. The prisoners were responsible for any improvements. The American doctors, including Poweleit, immediately began working to build some semblance of a medical facility. The “Zero” or “Z” wards (Tenney, p .68) were the most forsaken areas at O’Donnell—where men were placed to die.

Americans were dying at an alarming rate of nearly 100 a day; the Filipinos had a much higher rate. Many men were so near death, and with little medicine to treat them, the medical staff tried at least to provide some degree of dignity. Food and sanitation were also major problems, while the indiscriminate killings and tortures continued.

Camp O’Donnell was being used as a prisoner collection compound; it filled up rapidly to the point of extreme overcrowding. The Japanese began to disperse prisoners to other locations around Luzon, including the inhumane prisoner camp at Cabanatuan. Meanwhile, other prisoners were assigned to farming camps or to rebuild bridges, roads and airstrips. Poweleit would go out on a number of these work details, figuring conditions could not be worse than at Cabanatuan. During these times, Poweleit’s study of native plants for medical and food sources prior to the start of hostilities paid off by saving many lives. It did not, however, save him from being punched, kicked or hit with a shovel. On one particular work detail, he was working with a cart, being pulled by a caribou, hauling a huge water barrel. The animal unexpectedly lurched and the water barrel toppled. The Japanese guard hit him so hard Poweleit thought his back was broken. (Poweleit, USAFFE, p. 104). He managed to get back to his feet and with great pain, carried on. It would be weeks before the pain subsided.

In the fall of 1944, the Allies were preparing for the planned invasion of the Philippines and MacArthur’s much-anticipated promise of return. Furthermore, the Japanese were evacuating thousands upon thousands of American prisoners from the Philippines to Japan and its territories. Poweleit was one of 900 prisoners to be shipped out in late September 1944. His destination was Bilibid Prison, which was spared from Allied bombing because the letters, “P-O-W” were painted on the roofs of the cell blocks (Freeman, p. 369). Walking from Bilibid Prison, Poweleit could see sunken Japanese ships in the bay and the severe damage done to the harbor’s equipment.

Poweleit was loaded onto the Hokusen Maru, a “hell ship” as christened by the prisoners. The prisoners were forced down into one of the ship’s two holds where they were jammed in so tight that the men could hardly move and breathing became a problem. When the lids of the holds were slammed shut, it did not take long for the compartments to reach temperatures of nearly 120°. The men below were completely in the dark, and a great paranoia overtook them. Each morning dead bodies were pulled up out of the holds. The stench of sickness and death was overwhelming.

Two weeks of sailing brought the Hokusen Maru to Hong Kong. The men were allowed to spend some time on deck but on the second day in port, the pier came under a heavy air attack. The Hokusen Maru was not hit but much damage was done to the harbor. Following the close call, the hell ship pulled up anchor and headed out into the South China Sea.

The hell ships were not marked with any type of insignia identifying them as prisoner-of-war ships and were easy prey for Allied submarines. Unknowingly, submarine captains were sending Americans to their death. Two days out of Hong Kong, the convoy, including the Hokusen Maru, was attacked. Two ships were sunk. Poweleit, trapped in the ship’s hold, heard a loud ping and the ship jolted. A Navy POW later told Poweleit that the ship was hit by a torpedo but failed to detonate (Poweleit, USAFFE, p. 123).

The month-long journey finally came to an end when Poweleit’s hell ship docked at the city of Takao, Taiwan. Poweleit was assigned to the Shirakawa Camp whose prison population consisted mainly of enlisted officers. The men were suffering from symptoms of starvation. They received a fist-sized portion of rice each day but had to scrounge for additional food. Of all the varieties of plants and animals Poweleit had eaten to stay alive, he could not bring himself to eat the most abundant food source in the camp – rats.

On August 6, 1945. and again three days later, the United States dropped atomic bombs on Japan. News reached Poweleit’s prison camp on August 22nd that the Japanese had surrendered. The starved Americans would have to be slowly nurtured back to health. After a couple weeks of convalescence in Taiwan, the POW’s were flown back to the Philippines for more rest and medical attention.

Finally, many former prisoners, including Poweleit, boarded a US Navy ship, sailed past the Bataan Peninsula and the fortress Corregidor, and headed for San Francisco.

The trip across the Pacific Ocean took only five days. Poweleit’s thoughts were of his wife, Loretta, and his children, Alvie and Judith Ann. Leaving San Francisco by train, he arrived at Cincinnati’s Union Terminal. Catching a streetcar to Newport, he stepped off at the end of his street and walked home.

Alvin Poweleit rang the doorbell and a pretty little girl of four opened the door. “She stared at me and asked, ‘who are you?’ I told her I was her dad. She said, ‘were you with those Japanese?’ I told her, ‘yes’ and kissed her” (Poweleit and Claypool, p. 70).

Pat Ryan has been an American History teacher and an administrator at Holy Cross High School in Covington KY for over 40 years. He enjoys researching local history topics. His educational background includes degrees from Northern Kentucky University and Xavier University.

We want to learn more about the history of your business, church, school, or organization in our region (Cincinnati, Northern Kentucky, and along the Ohio River). If you would like to share your rich history with others, please contact the editor of “Our Rich History,” Paul A. Tenkotte, at tenkottep@nku.edu. Paul A. Tenkotte, PhD is Professor of History at Northern Kentucky University (NKU) and the author of many books and articles.

For further information, see:

Drury, Bob and Tom Clavin. Lucky 666: The Impossible Mission that changed the War in the Pacific. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2016.

Freeman, Sally Mott. The Jersey Boys, New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 2018.

Lawton, Manny. Some Survived: An Eyewitness Account of the Bataan Death March and the Men who lived through it. Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books, 2004.

Miller, Donald L. D-Day in the Pacific. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 2005.

Norman, Michael and Elizabeth M. Norman. Tears in the Darkness: The Story of the Bataan Death March and its Aftermath. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2009.

Poweleit, Alvin C., and James C. Claypool. Kentucky’s Patriot Doctor: The Life and Times of Alvin C. Poweleit. Fort Mitchell, KY: T. I. Hayes. 1996.

Poweleit, Alvin C., M.D., and James A. Schroer, M.D., eds. A Medical History of Campbell and Kenton Counties. Cincinnati: Campbell-Kenton Medical Society, 1970.

Poweleit, Alvin C. MD. Major US Army (Ret.). USAFFE: The Loyal Americans and Faithful Filipinos. 1975

Tenkotte, Paul A., and James C. Claypool, eds. The Encyclopedia of Northern Kentucky. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 2009.

Tenney, Lester L. My Hitch in Hell: the Bataan Death March. Washington, DC: Brassey Inc, 1995.

I was born cross-eyed and Dr. Poweleit did the surgery to straighten them when I was very small. I’ve been thankful my entire life and will forever be grateful to him for what he did. I’ll never forget going back to see him when I turned 16 and needed an eye exam to get my driver’s license. He looked intently at my file as we talked about my surgery and he gave me every reason to feel that he remembered me personally and my case in detail. I’ve always known that he was a POW, but reading his story here is especially powerful and I’m thankful not only what he did for me, but for his service and who he was as a man.

Dr. Powelite was my doctor from 1963 to 1970. It is true this dedicated doctor took care and stayed til he had seen the last patient. He would see patients who could not pay. I remember when he wrote his book . He told me that the conditions were so bad re the the Death March, he said a prayer to God, praying if he survived ,he would dedicate his life healing the sick and patients who needed him.

I am now 72 and I still remember Dr. Poweleit.

In my reading, I could not find if Dr. Powelite was awarded any metals.

Dr Poweliet would teach and work Northern Kentucky and Cicinnati then see patients at his office and would not leave until his last patient was seen. He was a eye ear nose and throat doctor with kindness and patience in his soul. He was loved and respected by all who knew him. His wife Loretta was a special person as well

It’s my Uncle Alvin Poweleit.,My mother’s side of the family. He was a very smart, talented and compassionate man. He went through a lot, but he worked very hard to achieve his goals.

I’m sure this is just a typo, but the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima on Aug 6th, 1945, not Apr 6th, as stated in the article. Also, what a sweet ending to a story of terrible hardship.

With gratitude, Mr. Decker, this has been fixed. And, yes, this is an amazing story. Dr. Poweleit was an amazing man.