By Jeremy D. Shea

Special to NKyTribune

Part 44 of our series, “Resilience and Renaissance: Newport, Kentucky, 1795-2020.”

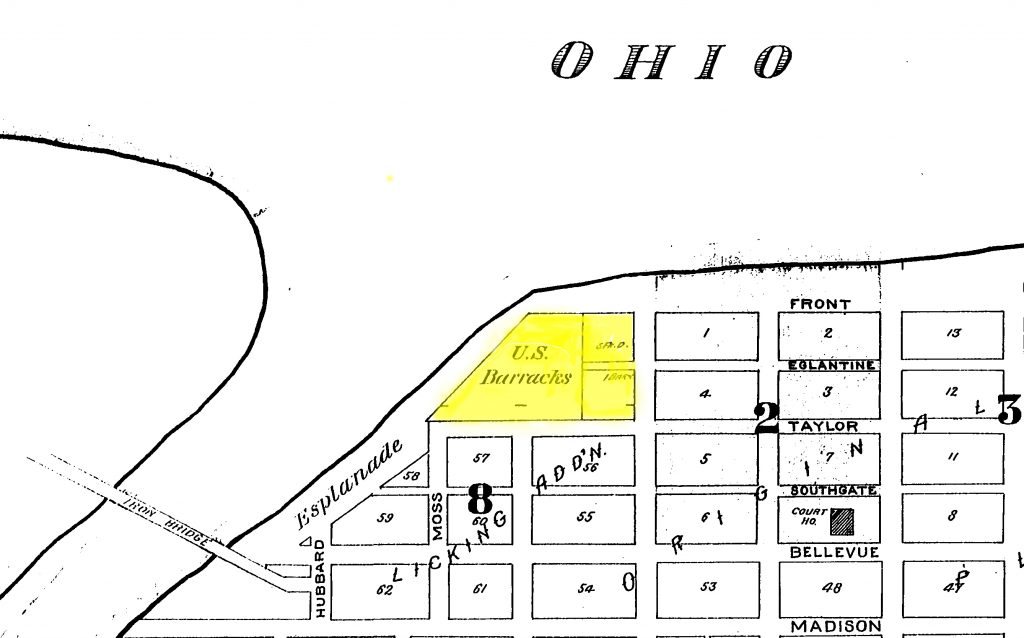

For many decades, Newport has struggled with an exotic yet unsavory past. For years it was known as Kentucky’s Sin City, a title associated with its wide-open gambling and drinking during the era of Prohibition. However, its seedy side began as early as the construction of the Newport Barracks circa 1803-1807 (Michael L Williams, Sin City Kentucky: Newport, Kentucky’s Vice Heritage and Its Legal Extinction, 1920-1991, MA thesis, University of Louisville, 2008, 16-17). The Barracks were situated at the confluence of the Licking and Ohio Rivers. (See this NKyTribune history column)

Historian James C. Claypool states that, “Newport was a frontier, too: a lawless slip of territory at the edge of civilization; a place where drinking, prostitution, gambling, gunplay and all-around carousing were the natural order” (David Wecker, Before There Was Vegas, There Was Newport, the Kentucky Post, September 4, 2004, A1).

Newport became a soldier’s town, attracting prostitution, gambling, and lawlessness. Williams asserts: “Around Newport’s present day West Third Street was a vice-ridden part of town called the ‘Temptations of Taylor Street’” (Williams, 16-17; Taylor Street was later renamed West Third Street). There, the world’s oldest profession (prostitution) was well established in the West End of Newport after the building of the Barracks. Many soldiers spent their idle time drinking at saloons and visiting brothels.

For many decades, a kind of live-and-let-live attitude prevailed in terms of prostitution. Only in the late 1800s did a serious movement emerge to make prostitution in the United States illegal, during the Progressive Era of circa 1890-1920. Part of the justification for legislation was related to public health, particularly the crusade to control social diseases. Movements to address alcohol abuse and gambling were also related.

On October 5, 1905, The Kentucky Post reported that a grand jury had been selected for the Campbell County Circuit Court to investigate gambling at Huber’s Garden at 16th and Monmouth Streets. Judge Berry, who was presiding over the indictment, delivered a lengthy speech to the jurors regarding gambling in Campbell County and Newport. In addition, he “also called attention to the existence of bawdy houses. These places, the court stated, thrived almost within the shadow of the Courthouse, and they should be driven out. The owner of the property used for immoral purposes should be indicted” (“Charges Grand Jury,” The Kentucky Post, October 2, 1905, 5).

From 1914 to 1916, Newport police were ordered to orchestrate a series of “vice raids” on brothels (bawdy houses, houses of ill fame) and prostitution. On June 18, 1914, Mayor Helmbold ordered Newport police “to cleanup vice that is beginning to make Newport its headquarters” (“Helmbold Is after Places of Ill Fame,” The Kentucky Post, June 18, 1914, 1). The mayor’s order derived its power from a February 1913 ordinance that allowed him to “issue such special or general orders as would tend to preserve the good morals, health and safety of the citizens” (“Helmbold,” 1).

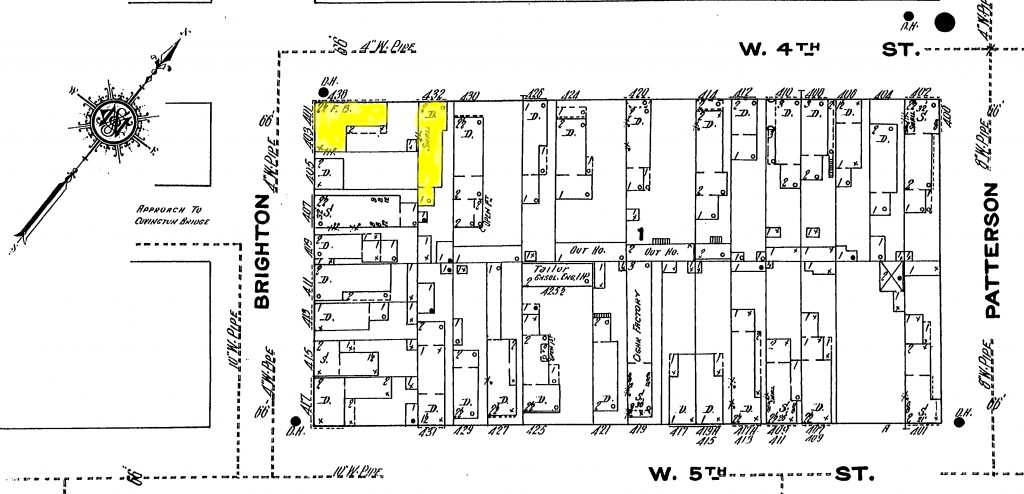

In 1916, the Newport Police Department started to hammer down on brothels, otherwise known as disorderly houses. Moreover, rumors were also circulating of corruption on behalf of the police for allowing and even visiting these houses. In February, a Campbell County grand jury brought indictments against six women “for operating alleged disorderly houses in Newport” (“Spectacular Report Made by Grand Jury,” The Kentucky Post, February 26, 1916, 1). Four of these women were operating houses in the West End at: 422 Central Avenue, Fourth and Brighton Streets, 432 West Fourth Street, and 324 West Sixth Street. This grand jury also investigated the possibility of police officers visiting brothels, but no concrete evidence was found to substantiate the allegation at that time. Yet five months later (July), a Campbell County grand jury claimed, “the Police Department was hit for permitting alleged operation of disorderly houses.” And apparently, these brothels were also “frequently visited by officers of law” (“Common Talk Anything Goes in Newport Says Campbell Grand Jury,” The Kentucky Post, July 1, 1916, 1).

On August 16, 1916, Newport began a campaign “against houses and women of a certain class” (“Women Are Fined, Agree to leave Newport Forever,” Kentucky Times-Star, August 17, 1916, 13). Nineteen (18 according to The Kentucky Post) women were arrested and appeared before Police Judge Buten (“18 Girls Leave Newport by Tonight or Go To Jail,” The Kentucky Post, August 17, 1916, 1). The houses were located at: Fourth and Brighton Streets, 432 West Fourth, and 417 West Fifth. These were some of the same women and brothels from the February indictments. The raids were overseen by Detective Van Lewden. All the women were charged with disorderly conduct, and four of them received an additional charge of “conducting an improper house.” Each woman was fined $15 and a 30-day jail sentence. However, “City Prosecutor Reuscher recommended suspension of the fines and sentences on condition that the defendants promise to leave Newport forever” (“Women,” 13). The raid actually stemmed from complaints to Newport city commissioners by Fort Thomas soldiers who were assaulted and robbed at these bawdy establishments.

On Monday, August 21st, Mayor Livingston asked for a formal gathering of the Newport Commissioners to “take drastic action on reports that inmates ordered by Police Judge Benton last week to leave town forever, have been operating dives in the western part of the town the last few nights” (“Willing To Go Limit of Fire Force,” The Kentucky Post, August 21, 1916, 1). One day later, another disorderly house was raided at 210 Columbia Street (“Vice Crusade Still Going in Newport,” The Kentucky Post, August 22, 1916, 1). In October, the city claimed to have rid itself of vice (“Last Trace of Vice is Gone Say Officials,” Kentucky Post, October 24, 1916, 1).

Meanwhile, national forces seeking the prohibition of the manufacture and sale of intoxicating beverages were reaching a crescendo. In 1917, the US Congress passed legislation paving the way for the Eighteenth Amendment (Prohibition) to make its journey through the states. Approval by three-fourths of the then-48 states was needed for passage. On January 16, 1919, Nebraska became the 36th state to ratify the Eighteenth Amendment. The subsequent passage of the Volstead Act by congress made national Prohibition effective January 17, 1920.

Prohibition raised awareness of the continued existence of vice in Newport. By May 1919, concerned Newport citizens tipped city officials that there was an “influx of women of alleged questionable character to the community” (“Allege Influx of Women,” Kentucky Post, May 1, 1919, 1). Complaints were also issued regarding a “den of women of low type and men of similar character loiter[ing] at Fifth and Patterson Sts.” (“Allege,” 1). This area of Newport had been associated with high rates of violence and murder only two years prior, in 1917. In October 1919, three women were arrested for heading a disorderly house on Chestnut Street (“Woman Caught in Vice Raid,” The Kentucky Post, October 7, 1919, 1).

Overall, however, Newporters chose not only to disregard Prohibition — they openly defied it. Prostitution, gambling, and the sale and consumption of illegal alcohol escalated in Prohibition-era Newport. Vice raids largely ceased in the city until 1922, at least according to the media. When they resumed, in 1922, the raids were initiated by Colonel H. H. Denhardt, who with state National Guard troops, had been called into Newport by the governor to quell a violent steel strike. (See: NKyTribune, Newport Steel strike ) (“Soldiers Started Out on New Raids,” Kentucky Times-Star, February 18, 1922, 1; “Troops at Scene of Strike,” The Kentucky Post, December 24, 1921, 1).

The new campaign’s main goal was to seize and destroy liquor stills and gaming devices. The “clean-up” also included stifling others vices, such as prostitution. Armored tanks were used in the raids for demolition purposes. Federal Prohibition officers were also involved in the effort. Mayor Joseph Herman and five Newport officials were “accused of having conspired to violate a Federal law through alleged failure to act in cases of violation of the prohibition act…” (“Soldiers,” 1). The Mayor proclaimed his innocence. The raid was not at all well received by Newport’s citizens.

Another raid occurred in January 1923. Three women were arraigned in court on January 18th (“Jury Demanded,” The Kentucky Post, January 8, 1923, 1). One was the operator of a brothel on 432 West Fourth Street, the scene of a raid six years earlier. A man was also arrested during the raid—he did not appear in court. The three women requested a trial by jury, which they were granted. Three days later, the jury decided a verdict of guilty, carrying fines ranging from $25 to $100, and jail sentences of up to 20 days. (“3 Women Sent to Jail,” The Kentucky Post, January 11, 1923, 1).

Like many madams and prostitutes, one of the women was a repeat offender. Multiple arrests for the same charge were indicative of the limited economic opportunities for women of the time period. The brothel that was maintained by one of the women was raided again in June 1923 (“Echo of Raid,” The Kentucky Post, June 7, 1923, 1). During the raid, six men were also arrested for “unlawful assembly,” two of whom were married. The men were only fined $10.

Clearly, the law was less stringent on male clients (“johns” or “tricks”). For example, a headline of an article in The Kentucky Post on February 22, 1926, speaks for itself, “Men Free but Women Fined” (“Men Free But Women Fined,” The Kentucky Post, February 22, 1926, 1). Five women and 23 men were arraigned in Newport Police Court, the result of a raid on a brothel at Fourth and Brighton Streets. The madam was charged with “operating a disorderly house” and fined $100. Four prostitutes employed by her were each fined $10. All 23 men were set free with no fines whatsoever.

The vice raids of the early twentieth century make it clear that prostitution flourished in the West End of Newport, particularly at the southeast corner of Fourth and Brighton Streets and at 432 West Fourth Street. This was considered the “red light district” of Newport (“Newport’s Shame,” The Kentucky Post, March 26, 1926, 4). A Kentucky Post editorial captured an historical glimpse of disorderly houses during the first quarter of the 20th century:

Newport has an old-fashioned red light district. A raid made by Newport police Tuesday night on one house is proof that the police know what is going on. But why not clean up the entire district. All night long machines [automobiles] are parked in front of the half-dozen houses at the…end of the Fourth Street bridge… [Because of a fire] The gaudy painted girls ran to the street in “house” attire…The proprietress [madam] stood guard at the door, in one of those swinging window affairs, which opened at the top and from which the visitor can be expected. A heavy wiring over the top of the door prevents intruders from forcing an entrance. Federal officials are frank in admitting the conditions in this section of Newport are worse now than at any time in their memory…they [disorderly houses] could not exist without the knowledge of the police…The public can have but one opinion if such a condition continues to exist, and that is that certain houses are more entitled to favor than others (“Newport’s Shame,” 4).

Despite the vice crusades that occurred during the early twentieth century, prostitution and the proliferation of brothels continued to thrive in Newport for decades thereafter. For example, in the 1970’s, Patsyann Maloney operated a prosperous house at Third and Saratoga Streets in Newport’s eastside. She related her experiences in a fascinating book entitled, The Making of a Madam: A Memoir (2008).

From the Newport Barracks and its neighboring “Temptations of Taylor Street,” to the Progressive Era and its vice raids, to the wide-open drinking, gambling and prostitution of the Prohibition Era, Newport’s colorful past recalls a city as diverse as any in America. Lying beneath the umbrella of Cincinnati across the Ohio River, Newport became a shadowy playground of forbidden fruits to the citizens of the region. Prosperity abounded, and for many decades, a medley of businessmen, politicians, mobsters, and others not only tolerated thee situation—they became enriched by its addictions.

Jeremy Shea is a graduate of NKU’s MA in Public History program. He resides in Cincinnati.

We want to learn more about the history of your business, church, school, or organization in our region (Cincinnati, Northern Kentucky, and along the Ohio River). If you would like to share your rich history with others, please contact the editor of “Our Rich History,” Paul A. Tenkotte, at tenkottep@nku.edu. Paul A. Tenkotte, PhD is Professor of History at Northern Kentucky University (NKU) and the author of many books and articles.

In 1959 I worked at a repair shop near Second and York Sts. and I believe it was on Tuesdays of each week I saw the police chief, George Gugle, drive up in his 1958 T-Bird and collect his payoff from each of the three “cat” houses that were in that block. He’d knock on the front door and the madame would come to the door and hand him an envelope. Gee, I wonder what that was for….LOL

I worked in Newport at the time that George Ratterman and his group of citizens and ministers were cleaning up Newport in the 1950s and 1960s. No, I didn’t work in that “industry” I worked for Metropolitan Life Ins. Such interesting times.

The article “Women caught in vice raid” was not in the October 17, 1919 article, it was in the October 7, 1919 , Page 1, of The Kentucky Post”.

Thank you, Dave. We will fix this.