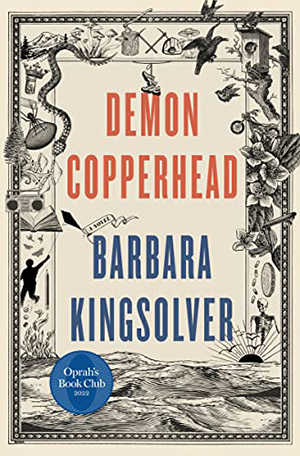

When I started reading Barbara Kingsolver’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, “Demon Copperhead,” I felt as if I were barely staying afloat. My fellow travelers — scores of characters featured in this powerful story – provided ballast that kept me from drowning in a sea of misfortune.

The first sentence, just five words, pulled me in. “First, I got myself born,” Damon Fields announces.

Known as Demon and nicknamed Copperhead for his red hair, he was born in a caul. This rare event, where an infant is delivered still inside an intact amniotic sac, carries superstitious baggage. Some cultures consider it a sign that the bearer is clairvoyant, while others assert the caul means a person is protected against drowning.

For Demon, it is the part about water that gives him hope for the future.

He reveals his attraction to the ocean on page 2: “Although I’ve not seen the real thing, just pictures, and this hypnotizing screen saver of waves rearing up and spilling over on a library computer. So what do I know about ocean, still yet to stand on its sandy beard and look it in the eye? Still waiting to meet the one big thing I know is not going to swallow me alive.”

In so many ways, Demon is in danger of being dragged down by the circumstances of his birth. His home is “dead in the heart of Lee County, between the Ruelynn coal camp and a settlement people call Right Poor, the top of a road between two steep mountains is where our single-wide was set.”

Not only did Demon live in that single-wide, he was born there. “That’s like the Eagle Scout of trailer trash,” he declares.

His teenage mother is an addict and his young father is dead before the child is born. Nearby neighbors, the Peggots, provide some stability. Mrs. Peggot, in fact, is the only one who calls him Damon “after everybody else let it go, Mom included,” Demon says.

Demon is our fearless narrator, smart-aleck and fast talking, yet he reveals insight and compassion beyond his years.

His mother is sober when she marries Murrell Stone, “Stoner,” to Demon. When the step-father reveals a darker and more abusive side, Demon’s mother goes back to drugs and Demon’s fall from what seemed like about five minutes of grace plummets him into the depths.

Demon’s plight is intensified by school, foster services, and poverty. Through the institution of foster care, he is taken in by families that bank on the payments received for admitting a child into their home. This reader never imagined that the stark realities of foster care could include placement with a truly demonic foster parent who used his charges for free labor.

As a result, Demon is always hungry, dirty, and trying to avoid further punishment and degradation. He and the other foster boys manage to make some connections, and Demon uses his gift of drawing as a way to develop what passes for friendship in an environment of cruelty and exploitation.

The novel is a retelling of Charles Dickens’ “David Copperfield,” which provided Kingsolver with a framework to tell a contemporary tale of the opioid plague and its impact on Appalachia.

According to the New York Times, on a book tour in England in 2018, Kingsolver stayed at Bleak House, where Dickens wrote much of David Copperfield. She and her husband were the only guests. When her husband went to bed, she settled into the study where Dickens had worked.

“I sat at his desk and I just started communing with Dickens,” she said.

“I asked him, ‘How do I do that”’ And he said: “Let the kid tell the story. No one doubts the child.’”

The conversation ended well for Kingsolver and her readers. In spite of the sadness and losses and betrayals that confront Demon and many of the other characters in the book, the reader sticks with it. From Day One, we are rooting for Demon.

Kingsolver has achieved something that straight reporting on Appalachia and its demons has been unable to manage. She weaves history into the story seamlessly, and explains some of the factors that have stacked up over time to create systemic unemployment, unremitting poverty, and the opioid epidemic.

She incorporates references to the Whiskey rebellion, the heritage of coal companies, and the misery of stripping tobacco in a combination of poetic language and hard facts.

It is a teacher explains the way coal companies became king:

“What they did…was put the shuthole on any choice other than going into the mines. Not just here, also in Buchanan, Tazewell, all of eastern Kentucky. These counties got bought up whole: land, hospitals, courthouses, schools, company owned. Nobody needed to get all that educated for being a miner…so they let schools go to rot. And they made sure no mills or factories got in the door. Coal only. To this day, you have to cross a lot of ground to find other work.”

Scenes portraying the opioid crisis are most disturbing, with descriptions of drug company strategies that began with companies looking at data and hand-picking hand-picked targets. Counties like Lee County were gold mines. They actually looked up which doctors had the most pain patients on disability and sent out their drug reps for the full offensive.”

The misery in “Demon Copperhead” is mitigated by the writing and Demon’s narration. Kingsolver keeps readers riveted, using Demon’s voice throughout, clearing a path that provides compassionate insight into how Appalachia got to its current state.

According to Demon, there are two kinds of economy: land versus money. “But not city people against us personally,” he says. “It’s the ones in charge, like government or what have you. They were always on the side of money-earning people, and down on the land people.”

Those earning money pay taxes, he remarks, but what people grow and eat, or work they swap with neighbors in not taxable.

“That’s like a percent of blood from a turnip,” Demon declares.

“Demon Copperhead” is published by HarperCollins.