By David Childs

Special to NKyTribune

Ever since I can remember, I have loved Christmas. I grew up in a very large family and my father (the late Rev. Hezekiah Childs) always made sure that my siblings and I had great Christmases. Even though my family did not have a lot of resources, dad would say “God will provide” and each year miraculously we would have an amazing Christmas. Dad knew all the carols and reveled in the Christmas Eve church services we attended each year. And no one could outdo my dad in gift giving and having the Christmas spirit.

In Charles Dickens’ classic Christmas Carol, the character Ebenezer Scrooge encounters the Ghost of Christmas Past, who takes Ebenezer back in time to witness the happy and sad times he encountered during Christmas. Like Scrooge, I wish I could go back and revisit the happy moments of my childhood Christmases. Although we can’t build a Back-to-the-Future style time machine and visit past Christmases, we can explore history and examine Christmas traditions of days gone by. In light of the holiday season, I will offer a brief history of Christmas in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries to help us understand how it has evolved over time in the US and Western society.

Although Christmas celebrations date back to the third century, many of the Christmas traditions celebrated today have origins in the 1800s. The nineteenth century brought about a transformation of the Christmas holiday from a relatively quiet religious observance to a grand cultural celebration marked by the influence of many European traditions. These are Christmas traditions and practices that have had a lasting impact until today. Many of the holiday traditions that people practice today in the Americas came from Europe. During the Victorian era, Prince Albert of the United Kingdom (1819–1861) introduced the Christmas tree to England from his native Germany. It thus became a centerpiece of the season’s festivities and ultimately made its way to being a staple in North America. Christmas trees of the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries were adorned with candles, sweets, and often elaborate handmade decorations.

The classic Christmas stories and carols we know today came from Europe. Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, was published in 1843 and became a major part of the Christmas narrative. The story captivated audiences with its timeless message of compassion, generosity, and the spirit of Christmas.

Similarly, beloved carols such as “Silent Night” (1818), “Hark! The Herald Angels Sing” (1840), “We Three Kings” (1857), “O Little Town of Bethlehem” (1868), and “Away in a Manger” (1885) were written during that same era and found their way into the hearts and homes of people. Community-centered celebrations became more prevalent. Carolers wandered the streets, spreading melodies of joy and cheer, while charitable efforts aimed at helping the less fortunate gained prominence during the holiday season, becoming staples of the holiday season.

their family. This illustration, appearing in the Christmas supplement edition of the 1848 Illustrated

London News helped to popularize Christmas trees.

Also during this time, the ancient tradition of gift giving experienced a resurgence in the 1800s. While the exchanging of gifts had been a part of Christmas celebrations for centuries. It became more elaborate and widespread during this period. It was more popular, due to the lack of resources, to give handcrafted presents and small tokens of affection to family and friends, as opposed to contemporary times when most people purchase gifts. Likewise, Christmas decorations during the nineteenth century were often unique handmade creations. By the end of the century, holiday decorations became more elaborate and more prominent in homes and public spaces, including candles, wreaths, garlands, and the classic mistletoe. Accompanying the decorations and gifts were lavish Christmas dinners for those families who could afford to do such a thing. Popular foods for Christmases of the Victorian era included beef, veal, turkey, venison and goose, as well as chestnut pie, fruit cake and Christmas cookies.

As Christmas celebrations became more popular and widespread, business-minded individuals quickly saw ways to monetize the holiday season. In this way, one of the notable shifts from the 1800s to the 1900s was the commercialization of Christmas. The popular era known as the “roaring twenties” saw the rise of consumer culture as many middle-class families had more disposable income. As such, Christmas became less centralized, simplistic, small-town oriented, and folksy and became increasingly intertwined with marketing and advertising. Retailers took advantage of the season, promoting gift- giving and creating a festive ambiance to encourage shopping. This commercial aspect of Christmas began to permeate popular culture, shaping the way people approached the holiday. But even in the midst of commercialism, there was still a sense of family orientation and closeness that was cultivated with new technology.

The rapid advance of technology played a significant role in how society began to define and experience Christmas. For example, as radio became more popular, it helped bring holiday traditions such as carols and Christmas specials into homes more frequently. Radio and later television solidified traditional notions of family togetherness, bonding, happiness, and holiday cheer, actions that define what is called in modern times, the Christmas spirit. Further, as electricity became more and more available in people’s homes, electric Christmas lights replaced traditional candles, adding a new dimension to the festive decorations. These new traditions merged with old ones, redefining modern ideas of Christmas.

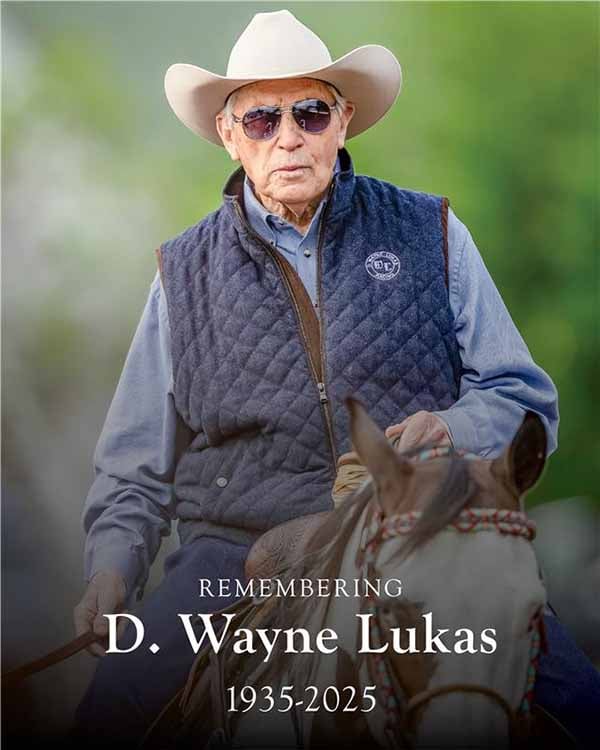

Store on West 7 th St. in Cincinnati, Ohio. (Photo provided)

As the century progressed, the holidays became a blend of emerging new traditions with iconic symbols associated with Christmas. Even the centuries-old myth of Santa Claus (also known as Father Christmas, Papa Noel, Krampus, Kris Kringle and St. Nicholas, amongst others) was merged with modern consumer products. In the 1930s, Coca-Cola’s depiction of Santa Claus in a red suit solidified the image of the jolly, gift-giving figure we recognize today. Along with televised versions of the famous poem “A Visit from St. Nicholas” by Clement Clarke Moore and other cartoons and films, the Santa Claus myth helped contribute to the holiday spirit and became ingrained in Christmas traditions.

The 1800s witnessed a marked transformation in how people celebrated Christmas in the United States, shaping many of the traditions and customs that persist today. It was a period when the holiday evolved from a quiet religious observance to a vibrant cultural celebration and looked completely different by the turn of the century. As the twentieth century progressed, Christmas became a blend of timeless traditions and emerging cultural influences. Families continued to gather for festive meals, exchange gifts, and partake in religious services. However, the holiday also became more diverse, incorporating elements from various historical and sociocultural ideas as the US and the Western world became more diverse. In this way, tradition intertwined with progress, reflecting the changing face of society. Despite the shifts, the underlying spirit of Christmas—a time of love, generosity, and togetherness—remained steadfast, transcending the changing times and shaping the holiday as we know it today.

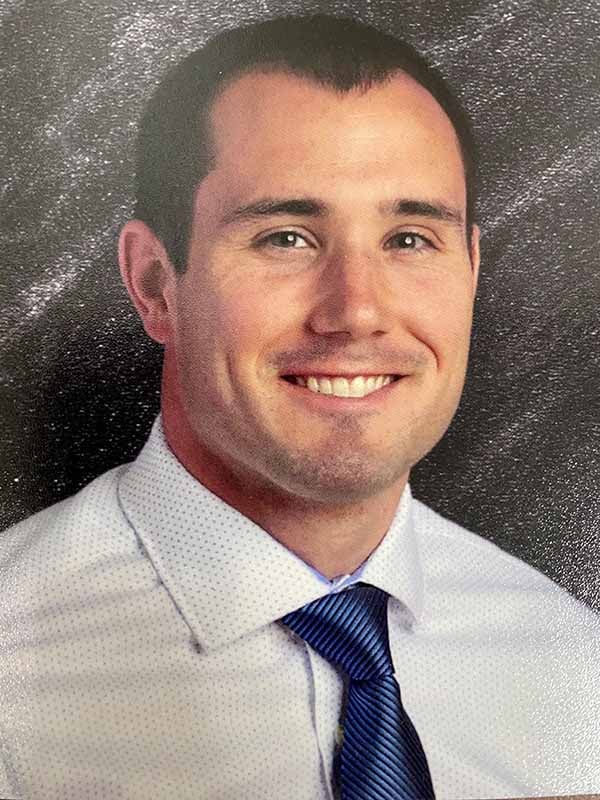

David Childs, Ph.D., has been a member of the social studies and history faculty at Northern Kentucky University since 2012. He was the first African American in the College of Education to earn tenure at NKU. He is an undergraduate of Mount Saint Joseph University, holds two master’s degrees, and earned his doctorate at Miami University of Ohio in African American history, educational leadership and philosophy, and an honorary doctorate in theological studies from Temple Bible College and Seminary in Cincinnati. He is the co-author of the book, Escaping from Home, a novel about slavery and freedom, available from Amazon. He is director of Black Studies at NKU, and he and fellow professors and students are presenting a research study at the Smithsonian on the role the Ohio River played in slavery and the Underground Railroad. Parts of the story here were originally published in Democracy and Me by Childs for a Cincinnati Public Radio project on December 14, 2023.

Paul A. Tenkotte, PhD is Editor of the “Our Rich History” weekly series and Professor of History and Gender Studies at Northern Kentucky University (NKU). He also serves as Director of the ORVILLE Project (Ohio River Valley Innovation Library and Learning Enrichment), premiering in Summer 2024. ORVILLE is now recruiting authors and documentarians on all aspects of innovation in the Ohio River Watershed including: Cincinnati (OH) and Northern Kentucky; Ashland, Lexington, Louisville, Maysville, Owensboro and Paducah (KY); Columbus, Dayton, Marietta, Portsmouth, and Steubenville (OH); Evansville, Madison and Indianapolis (IN), Pittsburgh (PA), Charleston, Huntington, Parkersburg, and Wheeling (WV), Cairo (IL), and Chattanooga, Knoxville, and Nashville (TN). If you would like to be involved in ORVILLE, please contact Paul Tenkotte at tenkottep@nku.edu.

Thank you, Dr. Childs. This is fascinating! As I read your article, my mind went back to a paperback book of traditional Christmas hymns I cherished as a child, and its many images of Christmas scenes from 18th and 19th century England. I had often wondered why the book was so focused on that culture and era, and your article helped me understand how historically relevant the artwork in that little book was.