The riverboat captain is a storyteller, and Captain Don Sanders will be sharing the stories of his long association with the river — from discovery to a way of love and life. This a part of a long and continuing story. This story first appeared in April, 2021.

By Captain Don Sanders

Special to NKyTribune

Thankfully, I have two trades that always provided a reasonable living: steamboatin’ and junkin’. The two were connected. If a boatman wasn’t tossing worthless junk into the river, he collected the good stuff in piles on the riverbank for hauling away to the nearest junkyard and sold for cash or traded for something in the yard that could find a better use on the river.

I learned to junk early on in my boating career thanks to my original river mentor, Walter Hoffmeier.

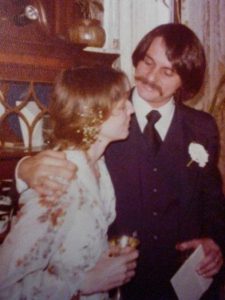

April is my month of anniversaries. Returning home from an erratic escapade trying to outrun myself following an unfulfilled romance and an especially hurtful relationship with a local business connection, my “neighbor girl” Peggy Ciulla and I married the 5th of April, 1980.

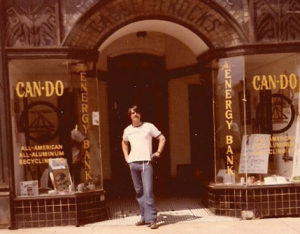

Following an adventurous five-day honeymoon in the Nation’s Capital, Peg and I jumped nose-deep into a business we knew absolutely nothing about. But it seemed like a good idea, especially when no one else in the three counties of the northern tip of Kentucky was doing it, so we started buying and selling used aluminum beverage containers or just plain old “aluminum cans.” Thus, on the 11th of April 1980, was born “Can-Do All-American All-Aluminum Recycling Company,” or simply, Can-Do Recycling.

Actually, the can-buying idea started in my backyard on Russell Street during the summer of 1978 when the shine from discarded beer and pop cans often seemed dazzling as they lay discarded in piles along streets, vacant lots, and roadways. From my boyhood junking days, I knew that a small lot of aluminum pots and pans always sold for more than did a large heap of iron or steel.

However, when I called a Cincinnati scrap dealer specializing in aluminum, the mocking voice on the other end of the phone line rebuked:

“Buddy, you’re nuts. Nobody will ever buy those cans.”

Of course, I didn’t believe the voice and looked in the telephone book (remember them?) and found a toll-free number for Reynolds Aluminum. But, this time, I was informed that their truck was “in my neighborhood three times a week.” Reynolds meant the “neighborhood” was the entirety of the metropolitan region of Greater Cincinnati, not just my southern side of the Ohio River, let alone anywhere near my home on Russell Street. At the time, I didn’t own a car, so I had no way of transporting the tall, clear plastic cans stacked in my backyard to Reynolds’ semi-trailer on the northern side of Cincinnati. But by the generosity of my sister-in-law Shirley Sanders, I borrowed her van and packed the cans to the Reynolds truck in the Swifton Shopping Center and sold the first load of 140 pounds of cans for ten cents a pound, or $14.00. I knew it was the best money I ever made, for there was no end to the source of the used aluminum cans.

On April 11, 1980, when Can-Do Recycling opened at #6 West Pike Street on the ill-fated “Old Towne Plaza” in downtown Covington, Reynolds paid us a premium so that we could pay their retail price to our customers and still have a small profit margin. As Can-Do was right around the corner from People-Liberty Bank, we paid all our transactions by check. A fear of having a large amount of cash on hand also prompted checks instead of dollars and change. The bank gladly cashed many payouts for less than a dollar by checks we ordered in lots of ten-thousand each.

Nearing the end of the first year, the city was upset that we were operating a scrap recycling business on the plaza. Mr. Fred Donsback, Covington’s Director of Urban Development, nearly lost his job for issuing the permit, or so some wag reported.

Can-Do was in a dilemma until Robert “Bob” Knoll, the Secretary of the NKY Beer Distributors Association, known from here on as the “Beer Barons,” approached me about joining them to start a joint enterprise to recycle the used aluminum, steel, and glass beverage containers that were the major contributors to the litter and waste generated after the consumption of their beverages.

With a working recycling operation in Northern Kentucky, the barons believed that it would help offset a statewide effort to establish a Deposit Law, or “Bottle Bill,” whereby monetary deposits paid on all beverage containers would cause all those in the beverage industry to become involved in the handling of the waste-end of their business, which none of them wanted.

By the first of the following year, a new recycling partnership began between the beer barons and me. As they wanted the words “beverage industry” in the name of the fledgling corporation, “Can-Do” was dropped.

All the while, my nephew, eight-year-old Robby Sanders, better known these days as Rob Sanders, the Commonwealth’s Attorney for Kenton County, Kentucky, had been interested in our recycling efforts. Young Rob’s name was perfect as it evoked a Robby-the-Robot-style aluminum can mascot, so the new recycling outfit took Robby’s name – ROBI – for the “Recycling Operation of the Beverage Industry.”

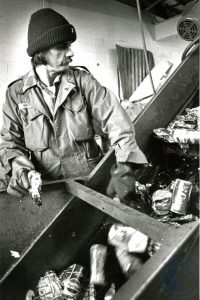

With the beer barons’ financial backing, I bought our first aluminum can sorting machine. Still, many of the beer and soda cans were made of steel, or ferrous materials, which had to be separated from the non-ferrous. With the aid of a powerful, magnetized roller head, the machine separated the steel cans, flattened the softer aluminum ones between a tire and a heavy steel wheel, and blew the smashed cans through a dragon-snout tube and loaded a truck or semi-trailer for hauling to a wholesale buyer. As I quickly discovered, a semi-trailer held around 12,000 pounds of loose, flattened cans, depending on how densely packed they were. Accurate records of the pounds of cans supposedly on a semi became important. I had to be constantly on guard that employees were not paying for “ghost cans” by “padding” the weight tickets — but that is a trade standard and need not be discussed further.

The new ROBI Recycling Center took root at an abandoned, two-bay car wash building on the corner of 14th & Neave Streets, in Covington, on the Budweiser Beer’s distributor’s property. The structure proved perfect for the fledgling operation, with two large bays having roll-up doors on both east and west sides with a long, enclosed room in the middle with solid, lockable doors at each end. The south bay became the can buying section, and the north bay held the scrap aluminum, copper, and brass scrap materials. The central hallway securely housed the office and the pay person, quite often, Peggy, who accepted the weight tickets through a small, bank-like window and paid the customers in cash. Gone forever were mountains of handwritten paper checks.

Within months, ROBI Recycling opened a Newport, center located in the old L&N Train Station, which was much larger than the Neave Street shop. Glass bottle recycling became large in the staff’s labors. Though the scrap glass price, called “cullet,” was just a few pennies a pound, it was far more labor-intensive than processing the pricier aluminum containers. The bottles and jars needed to be color-sorted into brown (amber), green, and clear (flint) with no rings, caps, or lids. Window and tempered glass were no-nos. Mixed broken glass and any other contaminants caused the rejection of a load, but paper labels were acceptable. The color-sorting of the glass was a customer responsibility. Although most first loads of bottle glass needed the assistance of the “crew,” as I called my helpers, return glass recyclers caught on quickly, and usually, their materials were flawless. As most of the “street cans” were grazed off the roadways by adult “pickers” before dawn, some of the more industrious glass recyclers were small bands of kids bringing in wagon loads of glass flawlessly sorted into corrugated, cardboard boxes. After emptying the boxed contents into larger, “Gaylord” corrugated containers, the smaller, seemingly insignificant boxes grew into miniature mountains reaching nearly to the ceiling of the train warehouse. Periodically, the corrugated mounts were bailed, shipped, and sold for scrap cardboard.

The ROBI Recycling operation was running like a well-oiled little machine. Or, as the old steamboatmen used to say, “running with a bone in its teeth on a double-gong.” Then, one afternoon, right around noon, a knock came at the office door. When I peeked through the peephole, a young, well-dressed businessman-type was standing on the other side. Slowly, I cracked the door until it was opened wide enough that the man thrust his hand forward and announced,

“Hello, I’m Bob Pohl, VP & General Manager of the Hudepohl Brewing Company, and I would like to talk to you about recycling.”

What a surprise to see such a distinguished scion of the beer-making industry of Cincinnati at my door. Hudepohl Beer, often called “Hudy” by locals, had been a favorite of the beer-imbibing German community, hereabouts, since at least 1885, when Ludwig Hudepohl II partnered with a friend and started brewing under the Kotte & Hudepohl Brewery label. Mr. Pohl soon made the details of his unannounced visit known. His brewery also wanted to have someone recycling the refuse of the beer business while giving themselves credit. Although I assumed my esteemed visitor personally knew all my ROBI beer baron partners, he made a most unusual request:

“The one thing I don’t want… if we do business, I do not need the local beer distributors to know that you and I are mutually involved in recycling.”

As soon as my visitor left, I tried to put all that was said together and understand why he wanted to start an independent recycling operation on the Cincinnati side of the river when a new startup would easily fall in step with what was already happening on the southern shore. The details of my contract of employment with ROBI clearly stated that I could go into “any other business outside the three counties of Northern Kentucky” at my discretion.

After weighing the pros and cons, I resumed my contact with the Cincinnati brewer. I found a startup location with the proper zoning located at the old Ace Iron & Metals scrapyard on Garden Street and Winchell Avenue, not far from where Crosley Field used to be before Interstate 75 smothered the area. Hudy had their fancy name picked out for the one-horse, under-capitalized, undertaking they dubbed the “Pride of Cincinnati Recycling,” but we workers still called the ramshackle operation “ACE.” The only endowment the brewery contributed was a temporary, billboard advertisement at the intersection overlooking the expressway. Nary a cent in startup capital changed hands.

Within a few months of managing both ROBI locations plus the one my toddler son, Jesse, called “Dada’s Ace,” I needed to raise money to continue the Cincinnati operation. Following a long, sleepless night, I concocted what I thought was a flawless plan. As ROBI was a stock company, and I was the majority stockholder, at least on paper, I would sell my shares to Drew N., whom I thought was my trusted second-in-command, and use the money that Drew assured me he could get from his bank, to capitalize Ace. Also, I proposed to remain on the ROBI Board of Directors as a recycling advisor for no compensation. In my mind, the plan seemed impeccable.

At the next ROBI Board of Directors meeting, I began my presentation. At the conclusion, the room was momentarily as quiet as Schutt’s Tomb until all hell broke loose. Ooooops….

Quicker than anything I’d ever seen, that band of scallywags called for a vote, and before I could say, “Oh, Crap,” I was voted out as the President of ROBI Recycling. According to my employment contract, though, I was still owed in the neighborhood of nearly $200,000 for the agreement’s remainder. But upon examining the employment pact, my attorney, a former meat hacker from a butcher shop on Willow Run, near where the old Covington Ball Park was when I was a boy, and whose law school tuition was financed by the Secretary of the beer baron’s association, failed to ensure the document contained the signature of the Secretary. Instead, I settled for a paltry amount as I could not withstand the time and financial burden of suing the brigands.

Still, I had Ace, but I desperately needed a location near where I could tap into my Covington customers. Commercial property was always a premium, even in the depressed neighborhood along both sides of the Chessie railroad right away in Central Covington. So I set out on foot, walking south along Madison Avenue as the 14th & Neave location of ROBI was less than a block off Madison. When I reached 19th Street, I crossed over the viaduct until coming to Russell Street, the street paralleling Madison Avenue on the western side of the railroad, and plodded northward.

Just a short distance before reaching 15th Street, I passed the open door of a neighbor saloon. Also on the property, I recognized two huge, empty commercial-style garages. Turning into the darkened barroom smelling of cigarettes and stale beer, I found one elderly patron sitting on a tall stool talking to a woman behind the counter. She was, as I discovered, Mrs. Elsie Nienaber, owner of “Neinaber’s Cafe,” that had occupied that location since it was known as the “Stockman’s Saloon” in the late 1800s.

After some schmoozing, Mrs. Nienaber agreed to rent a space in the farthest back corner of the closest garage where I could set up an aluminum can buying location. After nearly a month, though, Elsie told me that I had to get out of her garage for several reasons, but mainly, she didn’t want to be bothered. Behind the garage, paralleling Russell Street was a large gravel parking lot belonging to the machine shop next door, south of the cafe. Elsie said she didn’t mind if I parked a truck back there to buy cans. The lot, isolated from the machine shop, rarely if ever, was utilized by them. But after a month, the shop owner said I would have to pay a reasonable rent if I wanted to continue buying cans on his lot. Eagerly, I accepted. Within another month or so, Mrs. Neinaber informed me that if I were going to operate a recycling business so close to her door, then I would have to buy the bar, the double commercial garages, the residence over the cafe, and a small cottage on her property.

Here, again, Peoples-Liberty Bank was eager to cooperate. After we closed the deal, Elsie worked as a bartender until she taught me her version of the bar business. In early 1993, Peggy, Jesse, and I moved upstairs over the bar renamed the “Monkey Wrench Corner Cafe” for the street intersection in Old New Orleans where rivermen and seamen frequented the dives and joints along that ramshackle section of the Crescent City. Our new name was too long for the sign-painter to letter onto the old Pepsi Cola sign hanging from a pole protruding from the second floor above the cafe, so he just painted “Monkey Wrench” on the sign, and everyone called our place by that name.

Something was lost with the shortened name, I felt, as I recall the old steamboatmen filling in for us younger ones on gate watch after daylight hours so we could hit our favorite haunts in the French Quarter…

“Where ya’ going, boys,” they hooted and laughed, “Monkey Wrench Corner?”

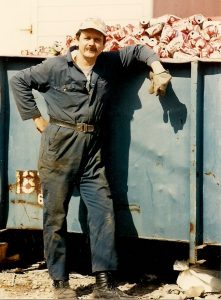

While the scrap metal recycling, renamed Can-Do Recycling, grew in the commercial-style garages, the bar business fizzled as fancy, new places also serving alcohol sprang up closer to the river. Peggy worked too many long hours paying recycling customers during the day and keeping Monkey Wrench open until closing time at 1 a.m. I’d quit drinking several years before, and after I persuaded our neighbor and last bar patron, Jim Bradley, who been a loyal Nienaber customer most of his adult life, to go to AA and get off the sauce, Monkey Wrench closed its doors. All our efforts and resources went into the recycling end of the property.

Those early years in the recycling business corresponded with the Reagan years in the White House. Though Reagan was great as the host of the Western TV series, “Death Valley Days,” his economics were murder on us. When Can-Do bought the Nienaber property, the mortgage interest rate was 18 ½%. Imagine. When the rate fell to 12 ½ %, I was overjoyed.

By 1987, our wholesale can price, as dealers selling at least 10,000 pounds of aluminum cans a week, fell to 17 ½ a pound. ROBI Recycling, now our close competitor a few blocks away, was getting the same wholesale price as us, but the cutthroats the beer barons had running the place in my absence were paying a flat 14 cents a pound for all weights. Can-Do, however, was paying a sliding scale of 12, 13, and 14 cents per pound, depending on the weight, so we had a slightly better margin, especially on the lesser amounts, which were the majority of the purchases of aluminum cans.

During the “Reagan Recession,” as I called those tough economic times, we could no longer pay our large mortgage payments. And though the bank kept cashing the checks Can-Do received for the sale of materials and allowed us to keep operating with that money, they never once mentioned us owing them for the mortgage payments. Instead, they “lent” us the payments and added them to the overall sum of money we owed.

After several agonizing months, almost miracle-like, the wholesale price for our can material skyrocketed from seventeen cents a pound to an astonishing 90-cents. Seemingly overnight, we were minting money. Immediately, we paid off all the mortgage back payments and other debts. But we could not have lasted through the bad times until the good ones without the trust and co-operation of People’s-Liberty, that may have been Star Bank, by then. I will always remember my loan officers’ courtesy, Ms. Lynn Moore (What a name for a banker lending money.) and Mr. Rick Frakes. But without the patience, trust, and guidance of Mr. Ralph Haile, Can-Do and all my recycling dreams would have been toast – burnt toast.

Joyce Sanders, too, needs remembering for, among many other contributions, keeping what some state and federal snoops called the “best-kept records of any small business” they examined.

As the 1980s slipped by and the ‘90s came upon the calendar, my soul began aching for the river. I had the “itch” that only a paddlewheel boat on the Mississippi River could scratch. Then Vanna White appeared on the TV, opening the first casino boat on the Upper Mississippi one morning as I sipped my morning joe before opening the front door where several pickers waited with their bags of cans. Meanwhile, I was negotiating with a likely buyer for the Can-Do Recycling operation. On the 3rd of April 1991, another April anniversary, the business sold, lock, stock, and sorting machine, and my family, now including little Jonathan, packed a U-Haul truck with all our plunder and set off for my latest dream of working aboard a gambling boat at old Natchez-Under-the-Hill.

Sunday, 11 April 2021, is the 41st anniversary of Can-Do Recycling’s commercial start. But the business, now known as “Can-Dew Recycling,” with no connection to the beverage, will be open at Neinaber’s old stand at 1510 Russell tomorrow (Monday) morning, under the guidance of the third owner, Phillip Turner. Can-Dew’s phone number, 859-261-8264, is the same one I had when living in Mrs. Albro’s manse further up the way towards the river. Phillip hinted that he has a new boat, a rather nice one, and he may be thinking similar river thoughts as I had when I bid the metals biz adieu and turned toward the water.

Captain Don Sanders is a river man. He has been a riverboat captain with the Delta Queen Steamboat Company and with Rising Star Casino. He learned to fly an airplane before he learned to drive a “machine” and became a captain in the USAF. He is an adventurer, a historian, and a storyteller. Now, he is a columnist for the NKyTribune sharing his stories of growing up in Covington and his stories of the river. Hang on for the ride — the river never looked so good.

Captain Don Sanders is a river man. He has been a riverboat captain with the Delta Queen Steamboat Company and with Rising Star Casino. He learned to fly an airplane before he learned to drive a “machine” and became a captain in the USAF. He is an adventurer, a historian, and a storyteller. Now, he is a columnist for the NKyTribune sharing his stories of growing up in Covington and his stories of the river. Hang on for the ride — the river never looked so good.

• • • • •

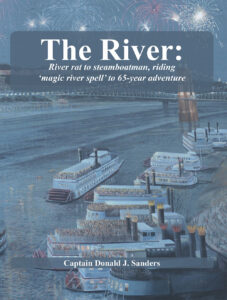

Enjoy Captain Don Sanders’ stories of the river — in the book.

Capt. Don Sanders The River: River Rat to steamboatman, riding ‘magic river spell’ to 65-year adventure is now available for $29.95 plus handling and applicable taxes. This beautiful, hardback, published by the NKyTribune, is 264-pages of riveting storytellings, replete with hundreds of pictures from Capt. Don’s collection — and reflects his meticulous journaling, unmatched storytelling, and his appreciation for detail. This historically significant book is perfect for the collections of every devotee of the river.

You may purchase your book by mail from the Northern Kentucky Tribune — or you may find the book for sale at all Roebling Books locations and at the Behringer Crawford Museum and the St. Elizabeth Healthcare gift shops.

Order your Captain Don Sanders’ ‘The River’ book here.

Capt. Don’s anniversary road of soul callings brings a river truth to light: The Calling to riverboat in some way or other. It’s a proverbial “Come Hither to the River.” It never goes truly away no matter if one is afloat and on top of the world or soured by its work-a-day world or “up the hill” and missing the work, the romance, the glory. True river blooded folks are always at some level spell-bound to their calling.

Oh my,the flood of memories this article brings to life. Yet again,Capt Don tells his tale in such a manner that we can feel we are there ! Alĺ the baaic business & “crew” organizing involved ,the “Can Do” perseverance too ,he learned on the river & it shows.. “Garbage picker” a group of boys once taunted as my friend & I culled through a “post tail gate party”dumpster. Instead of the Insult intended ,it brought the proud feeling of “making the community better” Don had instilled.. However. Not in the charitable vein I try to live now,, I retorted ” We pay your parets’ Welfare!” I must have hit a nerve,as they scuttled away. The next time I ventured to that lot, I found a couple of them doing the culling. I gave them the Can Do address & went to other hunting grounds. Thank you NKy Tribune for rerunning this great tale of the NKy spirit & the wonderful people both business & neighbors that made Covjngton so fantastic.. “Yelluw Star” dreams both on & off the river are strong ones not just an emblem on a pitman..