By Howard Whiteman

Murray State University

“Hey Howard, catch!” was all I heard as a green gelatinous mass headed my way and hit the water in front of me, splashing everywhere, to raucous laughter. I was at a church camp with some friends and dads as chaperones, a weekend retreat in the mountains. We had found a cement “tranquility pond” that had obviously become more of an actual pond based on the abundant frogs. Someone decided that throwing the egg masses of those frogs at each other was a good idea. I did not.

I did not throw back and although the melee continued, eventually we went back to the cabin and I turned in early, telling my Dad I wasn’t feeling well, which in some ways I wasn’t. I suddenly didn’t like these friends as much, and just wanted to go home. I didn’t like how they treated nature, and I still don’t.

I was not without sin as a boy, however. I shot many songbirds, along with the occasional squirrel, illegally it turns out, with air rifles. Since then, I’ve littered, dumped oil where I shouldn’t have, have used my fair share of pesticides, and of course have a huge carbon footprint given my American standard of living. The difference is that I feel a lot of guilt about those things, because for most of them I should have or do know better. I feel that guilt because of my worldview, something that was clearly learned early on, but has evolved over time.

Everyone has their own worldview, whether we think about it or not. A worldview is just how we see the world, and our place in it. One kind of worldview has to do with how we feel about nature, and our relationship with it. Our thoughts about our place in the world might come down to a simple question: does the world belong to us, or do we belong to the world?

The answer to that question has driven human civilization. Humans have been living as if the world belongs to us, because if it does, we can do whatever we like with it, like damming rivers, polluting air and water, destroying habitat to build cities, burning fossil fuels, and driving species to extinction. It even allows us to throw frog eggs at each other.

If we answer the other way, then we are thinking differently. We start to think about our role in Earth’s ecology. We begin to realize that everything we do has a cost to the world, that the Earth is finite, and that if our actions interrupt Earth’s ecological processes that nature provides to us, for free—we will feel the consequences. Knowing this, we try to find ways to live as part of the world, rather than apart from the world.

The inconvenient truth is that there is no scientific evidence that the world belongs to us. In contrast, there is abundant evidence that we belong to the world. Consider this basic question: can we live without the Earth? The answer is obviously no. Can the Earth live without humans? Why yes, it can, and did so very nicely before humans, or even our ancestors, appeared on the planet. Science shows us that we evolved as part of a natural process. We are not separate from the Earth; we are a part of it.

Yet our species has decided to be apart from it; we are above it, can control it, can bend it to our will. Except it turns out that nature doesn’t agree, and we have air and water pollution, disease, climate change, and the mega storms and fires that result. That is just nature responding to our populations trying to rule a planet that is not ours to rule.

None of these ideas are new. Aldo Leopold understood it very well in the early 1900s. Leopold was an ardent conservationist whose idea about how humans can live with the Earth, rather than against it, is called the Land Ethic, and most recently Ecocentrism. In his book A Sand Country Almanac, he described the Land Ethic like this:

“In short, a land ethic changes the role of Homo sapiens from conqueror of the land community to plain member and citizen of it. It implies respect for his fellow-members and also respect for the community as such.”

Ecocentrism puts the Earth first, and people second, because we are part of the world, and when we destroy it, our environment and people both suffer. Ecocentrism, a worldview where we belong to the world, provides a path to a sustainable future.

To follow this path, we cannot just recycle and drive electric vehicles and promote renewable energy. We have to change our worldview, and the worldview of our society and our political and economic systems. That is a big lift, but we have done so before.

At one point, worldviews in Western society were dominated by the benefits of slavery and the superiority of straight white males over other races, genders, and sexual orientations. Some people still believe a few of those things, but most people don’t, because our collective worldview has changed, and it did so over decades, not centuries. We can make the same changes with our planetary worldview, shifting from our current egocentric view to one that is more ecocentric.

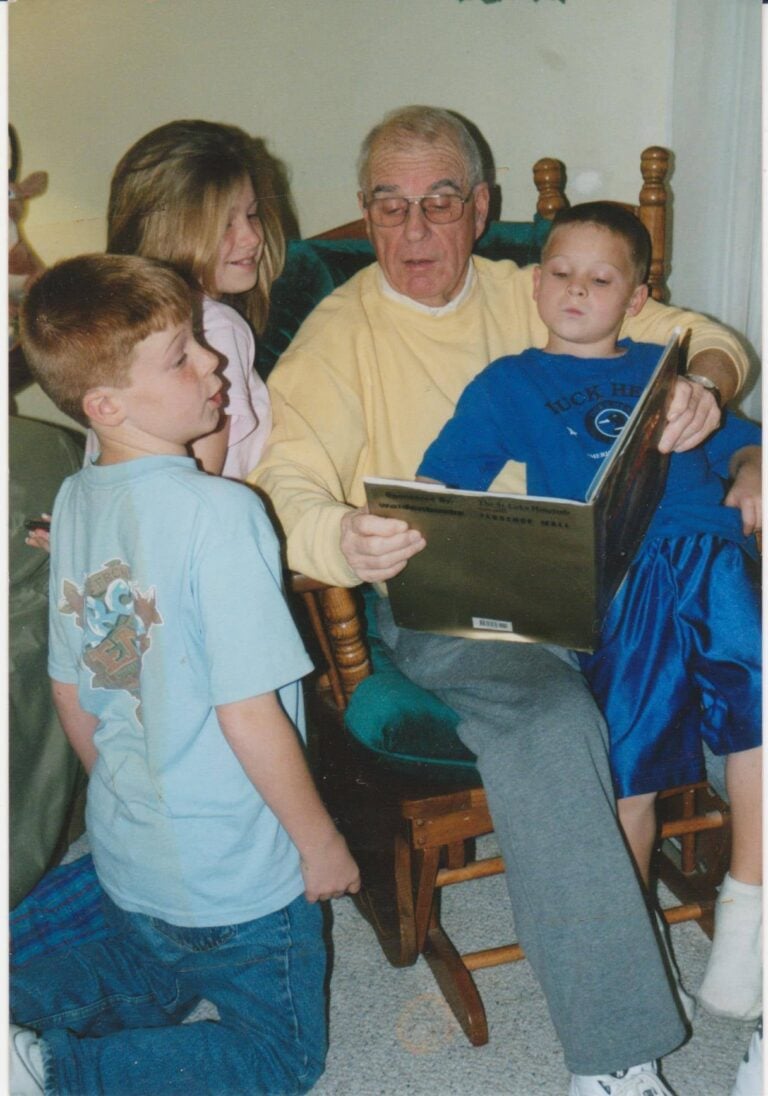

I’ve taught my kids not to throw frog eggs, not to shoot anything we can’t eat, and lots of other lessons that have made them more ecocentric. Their generation is much more environmentally aware than my friends and I were when we were growing up. That worldview will hopefully catch fire, but even so, we cannot wait for future generations to save what is left of the world. It is said “you can’t teach an old dog new tricks”. That may be true, but we are humans, not dogs, and we can learn at any age. It is time we learned from our past, begin to embrace the reality of our future, and start changing our worldview—each and every one of us—while we still can.

Dr. Howard Whiteman is the Commonwealth Endowed Chair of Environmental Studies and professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at Murray State University.