Editor’s Note: Third of a four-part series on Kentucky’s Parole Board

By R.G. Dunlop

Special to NKyTribune

The financial cost of incarcerating older inmates for life can be substantial and raises questions for some about whether release is a better alternative than continued confinement, especially since the likelihood of reoffending is relatively slight.

Kentucky Supreme Court Justice Michelle Keller’s opinion noted that life sentences result “in increased corrections costs, as the system must bear the burden of housing an aging inmate population.”

Prison Policy Initiative Senior Policy Analyst Emily Widra’s August 2023 report referred to the “steep costs of incarcerating older inmates,”

The U.S. prison population is aging, at a much faster rate than the nation as a whole, and older adults represent a growing portion of people arrested and incarcerated each year, according to Widra’s article. “And while prisons and jails are unhealthy for people of all ages, older adults’ interactions with these systems are particularly dangerous, if not outright deadly,” Widra wrote.

“It doesn’t make much sense to spend so much money locking people up in places that are not only dangerous to their health but more costly to care for them — especially when there is little public safety argument to justify doing so. Prisons are gearing up to become nursing homes, but without the properly trained staff and adequate financial support.”

Jim Peterson, a longtime criminal-justice advocate and a cousin of murder victim Robert Peterson, said that if Karen Brown were to live until the age of 87, Kentucky “will have spent about $2 million on her, for what? Revenge, retribution? Kentucky seems to have a habit of pulling defeat from the jaws of victory. A poster child of rehabilitation rots away in prison because of the inability to find forgiveness.”

Asked about the role, if any, of forgiveness in his thinking, Don Turpin, Michael Turpin’s father, said: “Not on my end. They took a human life that was totally unnecessary.”

He agreed that keeping Karen Brown, Elizabeth Turpin, and Keith Bouchard locked up is costly.

“But that’s where they should be,” Don Turpin said. The state ”could have ended that a long time ago by giving them the death penalty. The cost of gas is pretty cheap.

“The government wastes its money on a lot of senseless stuff. One price that I’m willing to pay is to keep them locked in.”

William Ray Stark was convicted of more than two dozen counts of robbery and sentenced to a total of 318 years in prison in 1990.

Stark, who is 57 years old, now has been locked up for more than 35 years. He has been denied parole six times since 1999, most recently in 2022 when he was given a five-year deferment, state records show. He will be eligible again in July 2027.

The state Department of Corrections said in response to a reporter’s inquiry that it did not have information about the cost of incarcerating specific inmates, including Lance Conn, Steve Nunn, Karen Brown, Elizabeth Turpin, Carlos LeeThurman, and several others.

But during the 2022 fiscal year, Kentucky spent a total of more than $600 million on corrections, including more than $355 million on adult correctional institutions, according to the state Department of Corrections’ 2022 annual report.

Inmate psychological state at time of offense raises further questions

In addition to inmates aging in prison, lengthy prison sentences meted out to minors and young adults also raise questions about how long they should remain in custody.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2005 that it was unconstitutional to impose the death penalty on a juvenile offender less than 18 years old at the time of the crime.

“A lack of maturity and an underdeveloped sense of responsibility are found in youth more often than in adults and are more understandable among the young,” the Supreme Court concluded. “These qualities often result in impetuous and ill-considered actions and decisions.”

Attorney Vincent Aprile made those and other arguments to the parole board on behalf of Blake Walker before Walker was pardoned in 2018 after serving more than 16 years in prison.

Based upon neurological science, Walker was so young at the time of his crime that “his brain had not formed completely and wouldn’t until between the ages of 25 and 30,” Aprile said in an interview. And Walker was ”more likely to commit spontaneous actions without thinking it through.”

Tessa Bialek, managing attorney for the Civil Rights Litigation Clearinghouse at the University of Michigan, wrote in a paper published in May 2024 that “the psychosocial maturity of youths differs fundamentally from that of adults.”

“Studies also showed that youths are likely to outgrow criminal behavior, which for young people typically reflects the transient qualities of youth rather than irreparable criminality,” Bialek wrote.

The long-term confinement of former juvenile offenders with serious mental-health issues poses yet another set of challenges for society in general and for the criminal-justice system in particular.

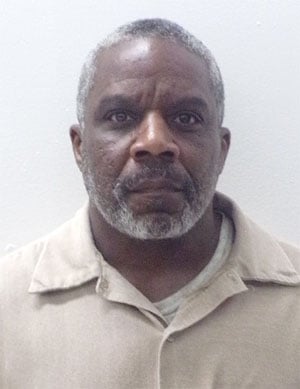

Michael Carneal has served more than 24 years in adult prison. While many inmates have served more time, relatively few have gone to prison at age 17, as Carneal did after pleading guilty but mentally ill to killing three students and wounding five others in a 1997 shooting at Heath High School. In June 2001, he was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole for at least 25 years.

Carneal was 14 years old at the time of the McCracken County shooting and suffering from hallucinations. Following his arrest, he was evaluated by five mental-health professionals, some hired by the prosecution, others by the defense. All five agreed that Carneal was competent to stand trial. None thought he was legally insane at the time of the shootings, court records show.

Following his conviction and sentencing, Carneal was taken into custody by the state Department of Juvenile Justice until he turned 18 in 2001. Then he was reassigned to the Kentucky State Reformatory, an adult prison. At the time of his transfer, DJJ officials said Carneal was “severely mentally ill and had developed paranoid schizophrenia,” according to a July 2011 opinion by U.S. District Judge Thomas Russell.

Once at KSR, Carneal was placed in the Correctional Psychiatric Treatment Unit, where he was given a new medication in 2002 and “experienced a marked improvement,” according to Russell’s opinion.

In 2004, Carneal’s lawyers asked two of the five medical professionals to reexamine him. One concluded that he was “seriously ill at the time of his crime…and that he appears to have been acting in response to command hallucinations, which he was not able to resist.”

The other concluded that the initial diagnosis of Carneal “was incorrect, that he did in fact suffer from paranoid schizophrenia,” and that his opinion that Carneal was mentally competent in 1998 to stand trial “was not correct.”

And according to Russell’s opinion, “records and the treating doctors indicate that Carneal has consistently been diagnosed with and treated for some type of major mental disorder related to paranoia, delusional thoughts and depression since his entry into the penal system in 1998.”

“No one can dispute that for over a decade, Carneal has been under the care of psychiatrists and psychologists that have consistently regarded him as mentally ill and treated him as such,” Russell wrote

Nevertheless, Carneal’s legal challenges to the validity of his guilty plea, conviction, and sentence were unsuccessful, and ended in October 2013 when the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear his case.

Carneal had consistently been housed in the Kentucky State Reformatory’s psychiatric treatment unit or “in a dorm for mentally ill inmates,” Russell’s opinion stated.

He is still confined at KSR, state records show, but it’s unclear how much or what type of treatment, if any, he has received during the past 13 years. The state denied a reporter’s request for his medical records while in custody, on the grounds that the records are, by law, confidential. Carneal declined to be interviewed, according to the state. And his parents and his most recent attorney did not respond to numerous requests for comment.

Carneal was denied parole in 2022 and was ordered to serve out the entirety of his 120-year sentence, which he will have to do barring a successful legal challenge, or a commutation (shortened sentence) or a pardon (elimination of punishment) by a Kentucky governor.

Carneal testified at his September 2022 parole hearing that he was still hearing the voices in his head that had plagued him since the time of the school shootings, but that he was better able to resist them.

Were he to be released, Carneal and his parents said at the hearing, he would live with them and continue to receive mental-health treatment. The board nevertheless denied his parole.

Previous: Kentucky’s parole board functions are complicated, and little-known to public

Next: Cost of incarceration may outweigh risk certain inmates would pose if granted release.