By Howard Whiteman

Murray State University

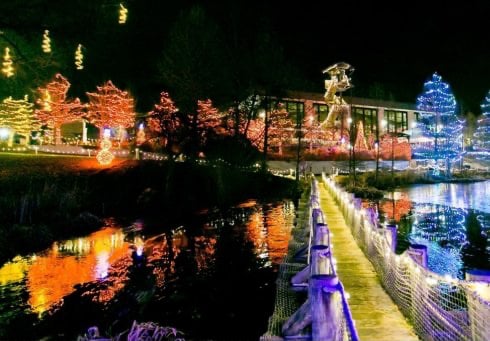

As darkness settled in at the end of an evening event at the Land Between the Lakes’ Woodlands Nature Station, the naturalists on hand worked to get the captive coyotes howling, in hopes of persuading their larger cousins to do the same.

As the coyotes started to yip on one side of the gathering, the red wolves on the other side did as well. We were all treated to an amazing chorus, one that I will never forget, in part because red wolves are among the most endangered species on the planet. Their howl reminds us that they still exist, and maybe we should figure out how to restore them.

Red wolves were once the dominant predator in the eastern U.S., and historically ranged from Pennsylvania to Texas. They are endangered for a multitude of reasons, including extirpation by humans, habitat destruction and fragmentation, and the recent expansion of the much more adaptable coyote. Coyotes have outcompeted red wolves by being able to live within the human matrix and also occasionally interbreed with them, reducing the separation between the species. The coyote problem only exists because European immigrants took worked tirelessly to kill every last predator.

Luckily, our ancestors didn’t succeed, and wildlife and conservation biologists have been working hard to try to bring predators back in a way that allows them to coexist with humans. Biologists are doing this not just because of the moral arguments against extinction, but because predators are vital parts of functioning ecosystems, and humans need healthy ecosystems for our own survival.

Many predators play “keystone” roles in ecology. A keystone is a critical, wedge-shaped piece of a stone arch which helps keep the other stones in place. If you pull that one, “key” stone out, the entire arch falls to pieces.

Similarly, keystone species are so intertwined with other species that when you lose one from the community, the biodiversity of the rest of the ecosystem begins to fade.

Reintroduction, however, can restore diverse communities.

Predators are often keystones because they are so interactive, eating many different prey, or, more often, because they consume a species that has a negative effect on the community when it is abundant. In the east, it is likely that red wolves affected whitetail deer, which are currently out of control. Predators are also important in disease regulation, and their absence in most of the United States helps explain why chronic wasting disease has spread so quickly in our deer herds.

We didn’t know all this science when we started decimating predators. We just jumped in and did it, thinking all predators were bad. But ecology has shown us, time and time again, that predators are important. When predators are removed, ecosystems collapse; yet we rely on healthy ecosystems to live, because of the clean water, air, and other services that we get from them, for free. Predators are not only good for ecosystems; in the end they are good for humans, even if living with them affects our lifestyle.

From the multiple reintroductions of gray wolves, the restoration of the Florida panther, and the management of black bears in the southeast, biologists have been trying to right these wrongs. Perhaps it is time we did so with red wolves as well, as difficult as that might be.

By the early 1900s, red wolves had disappeared except in the backcountry of Texas and Louisiana. Realizing they might go extinct, the US Fish and Wildlife Service captured 14 wolves and started rearing them in captivity. By the 1980s, red wolves were extinct in the wild, and restoration began in 1987, when the first pack was released in Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge, off the coast of North Carolina. Since this time the population has expanded to over 100 wolves in and around the refuge, with more wolves spread throughout the country in captive breeding programs. One of the breeding programs is at Land Between the Lakes, which has been involved in the red wolf recovery since 1991, and just last year produced four pups. With only 250 red wolves left, every new pup matters.

It is difficult to reintroduce red wolves into the eastern U.S. because it is already so different from what it used to be. There are few true wilderness areas and very few large expanses of remote public lands like the west, because we have converted the east into a human-dominated matrix.

In contrast, wolf reintroduction works in the west in part because of the expansive public land and wilderness. The habitat is not as fragmented as the east, and not converted as much into agriculture, industry, and urban centers. There are major conflicts, particularly with livestock owners; but can you imagine what those and other conflicts would be like in the eastern U.S.? They quickly magnify.

Our success in restoring wolves to the west, as contentious as it has been and continues to be, has allowed biologists to learn a lot about wolf restoration: what works and what doesn’t. Perhaps these experiments will help us find a path forward for red wolves, and figure out places where they might find a foothold and not let go.

This summer, working at my field research site in Colorado, I learned that some of the wolves that were recently reintroduced to Colorado were a lot closer to us than I thought. I realized that a dream of mine was now within reach: packing up after a long day of sampling, I hear that first wolf howl, a sound that has not been heard in those mountains, by any human or elk or deer, since the last World War. Today I am confident that I will hear that howl, that my dream is going to be reality, when just a few years ago it was nothing but a joke. That fact — knowing my dream is about to come true—makes me wonder about those of us dreaming about red wolves.

Red wolves may never again roam the eastern U.S. Yet, there is a path forward for them if we can maintain adequate habitat and minimize conflicts with humans and coyotes. The success of captive breeding programs shows us that there is hope, if humans can find the willpower to set aside some space for this critically endangered species.

I hope that all of us get to hear the howl of a restored wolf, no matter where it lives. But one day, perhaps you, or your children, or your grandchildren, will hear what I just heard, the howl of a red wolf, except that red wolf will, like its western relatives, be wild, free, and helping to keep our ecosystems healthy. That is another dream worth living.

Dr. Howard Whiteman is the Commonwealth Endowed Chair of Environmental Studies and professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at Murray State University.