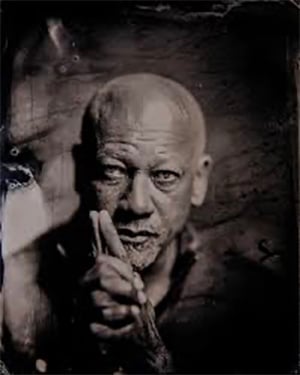

During a recent presentation at Murray State University, Frank X Walker promised not to make the audience too uncomfortable. Then the award-winning poet paused and leaned into the microphone, adding the word “Yet” in a conversational coda.

“There are things about history we don’t know,” he said, reflecting on his own public education, growing up in Danville.

He remembers being taught that slavery was somehow different in Kentucky, not like other southern states. He refuted that myth by reading his poem entitled, “Ain’t no plantations in Kentucky,” which begins with the phrase, “…unless you count…”

The list that followed started with Alexander Plantation House and then skipped through the alphabet to include familiar names like Ashland, Fern Hill, Maplewood, Oxmoor, Rocky Hill, Slead House, ending with Waveland, Wickland, and Woodstock.

Seventy-two plantations are identified. The names still exist in Kentucky, although no longer associated with wealthy slave-holding enterprises but tagged on malls, tourist attractions, and wedding destinations.

From there, the poet remarked, “The story gets uglier and more uncomfortable.”

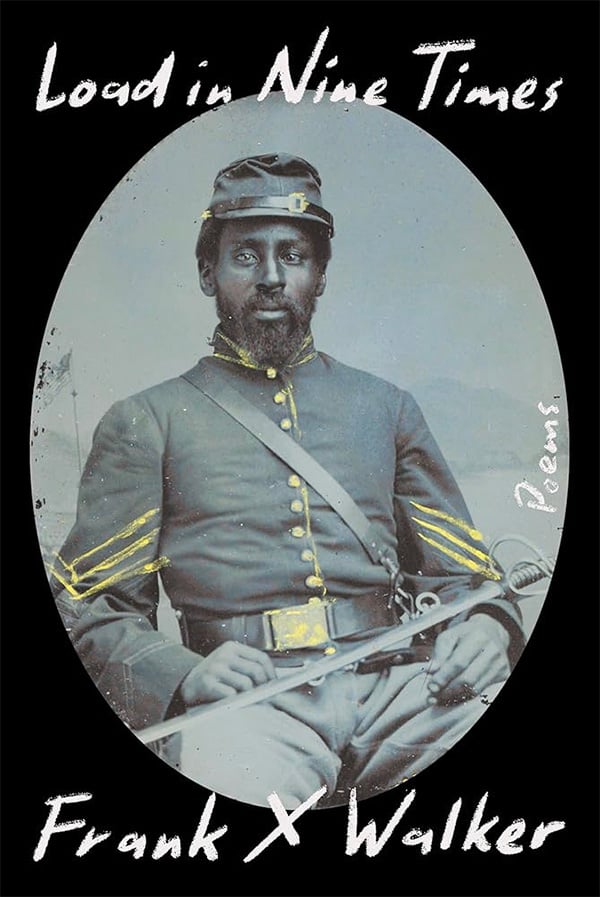

Walker, professor of English and African American and Africana Studies at University of Kentucky, explores historic truths in his current book of poems, “Load in Nine Times,” published by W.W. Norton and Company. In May, the rigorously researched collection was awarded the 2025 PEN/Voelker Award for Poetry. Earlier this month, as the 2025 Clinton and Mary Opal Moore Appalachian Writer-in-Residence at Murray State University, Frank X Walker presented a reading and lecture to a full house in MSU’s Curris Center Ballroom.

“Load in Nine Times” weaves historical artifacts and personal history into poetry that informs audiences with rich language and poignant images. According to UKNOW, University of Kentucky News, “The collection challenges prevailing perceptions of Kentucky’s history by offering a nuanced exploration of identity and heritage.”

For example, a poem entitled “Why I Don’t Stand,” intersperses lines from, “My Old Kentucky Home” with text from actual ads for slave auctions. The poem juxtaposes the opening lyrics —

Oh, the sun shines bright

On my old Kentucky home,

‘Tis summer, the darkies are gay.— with lines from a historic poster proclaiming:

I will pay more for likely NEGROES

Than any other trader in Kentucky.

Another blurb offers a twenty-dollar reward for return of “A Negro Girl named Fatima,” described as “a bright mulatto girl.” The twenty dollars includes Fatima and her “TWO CHILDREN, Rufus and Rachel.”

Commenting on the “mulatto” reference, Walker said, “People never talk about it.”

Doing the kind of research that validates this and the other poems in the book was not easy. “If you dare to look long enough,” Walker claimed, “you’ll be in tears.”

“New Orleans was the worst place to be a slave,” he also explained, “but Kentucky was not a benign place either.”

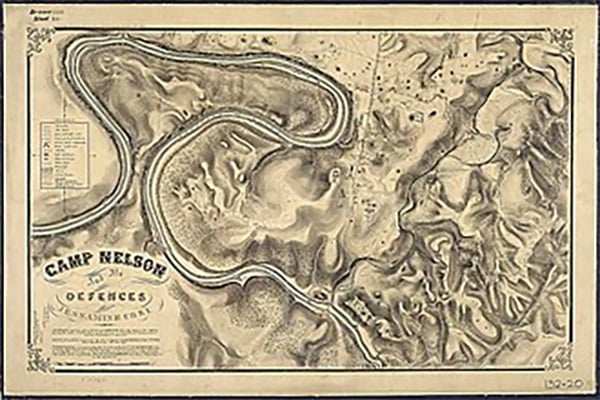

The story behind Kentucky’s Camp Nelson is told through poems that re-imagine the voices of Black Civil War soldiers, inspired by rigorous archival research.

“Kentucky had the second-highest number of Black enlistees during the Civil War, according to Walker. Louisiana had 24,052 with Kentucky at a total of 23,703.

Recruitment posters, some of them with copy written by Frederick Douglass, invited Black men to enlist, encouraging them with promise of food and clothing. They were able to bring their families with them to Camp Nelson, Walker explained, adding, “If you signed up you became a free man and so did your family.”

Photos from the era documented Black families at Camp Nelson and the Black soldiers who fought. “You can tell they have swagger,” Walker remarksed “Their pride is evident. They fought for their freedom and their families.”

While doing research for the poems, Frank X Walker learned that he had three relatives on both sides of his family who were stationed at Camp Nelson. “This was news we never knew,” he said.

During the presentation, he projected an image from an official Civil War document in which his relative, Mary Edelen, was making a widow’s claim regarding her husband’s pension. When Walker noticed an X between the first and last names of Mary Edelen, he realized the X was Mary’s legal signature.

That is when he changed his name to Frank X Walker. “Mary was reaching to me across time,” he said.

“Load in Nine Times” covers the Civil War and its aftermath, including domestic terrorism that involved burning, raping, and pillaging, especially directed at Blacks who owned land or had a business during Reconstruction.

The book features three ads in which families seek relatives who were lost to them during the slave era. Augustus Bryant and Lutitia Bryant, for instance, were trying to find their five children, “whom we have not seen for four years. They were in Charlotte, N.C. or at Rock Hill when we last heard of them,” it goes on.

“N.B. – These persons were formerly own by John L. and Virginia Moon, of Augusta, Ga,” it ends.

The presentation lasted about 90 minutes and the book, in barely more than one hundred pages, invites readers to delve into this history by providing a bibliography, explanatory notes, and a timeline.

One item on the timeline is February 24, 1865, the day the Kentucky General Assembly refused to endorse the end of slavery and voted against ratification of the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery except as punishment for crime. It took one-hundred-eleven years — to March 18, 1976 – for Kentucky to symbolically ratify the 13th Amendment.

A footnote to a June 19, 2024 article by Linda Blackford about the Kentucky timeline in the Lexington Herald Leader said, “As always, thank goodness for Mississippi. It did not ratify until 2013.”

Constance Alexander is an award-winning columnist, poet, playwright, and president of INTEXCommunications in Murray.