When Chet Hand explains why he got involved in politics, he keeps coming back to January 6 — and especially to the buses.

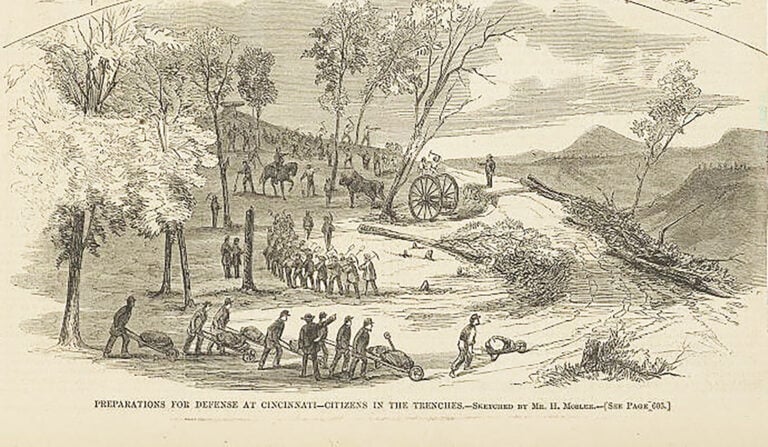

By his own telling, Hand helped organize two tour buses carrying about 110 people to Washington, D.C. to hear Donald Trump speak. His group, he says, included pastors, families, grandparents, and kids. They prayed, listened to Trump, and walked toward the Capitol. Then, he says, they saw something that rattled him: several tour buses pulled up close to the Capitol, unloaded crowds of people, and sent them running toward the building. Soon after, flash bangs went off. Hand gathered his group and left, believing the country was slipping away right in front of them.

That reaction makes sense. Seeing organized busloads of people flood into the heart of the nation’s government on a day driven by claims of a stolen election should alarm anyone.

Where Hand’s story breaks down is what he says next. He insists those buses had nothing to do with Trump, suggesting they might have been Antifa, federal agents, or some unknown group. But the facts don’t back that up. January 6 wasn’t random. It was planned, funded, and organized. Wealthy Trump donors paid for the rally and its logistics. One of them was Julie Fancelli, a Publix heiress who helped bankroll the buses that brought people to Washington. The buses Hand saw weren’t a mystery — they were part of the same Trump-centered operation that brought his own group there.

That’s the contradiction at the heart of Hand’s account. He trusted his instincts enough to know something was wrong that day, but not enough to follow the evidence to its clear conclusion. He recognized coordination and danger, then stopped short of connecting it to Trump and the money behind the event.

That blind spot matters. Trump didn’t just talk about pardons — he has already issued broad pardons covering people who broke into the Capitol, including those who were convicted and those who were still awaiting trial. The same movement Hand says wasn’t responsible has since claimed ownership of what happened, rewarded the participants, and erased accountability.

Chet Hand wants to be known as a straight shooter — someone who tells it like it is and stands up for Boone County families. And to be fair, his gut reaction on January 6 was right. What he saw scared him because it should have. But being a straight shooter for Boone County means following the facts all the way, even when they’re uncomfortable. It means being willing to say, “I got part of this wrong,” and naming who really organized and paid for what happened that day.

January 6 doesn’t need conspiracy theories or half-answers. Responsibility for what happened is not hard to trace. Boone County deserves leaders who can look back at that day, speak plainly about it, and correct the record when the facts demand it. If a leader can’t — or won’t — do that, voters should think carefully about whether he’s prepared to lead with honesty when it matters most.

Brian Maurer, a digital marketing professional and language teacher, lives in southern Boone County with this family.