Part 2 of a three-part series on the history of the Licking River.

by Paul A. Tenkotte

Special to NKyTribune

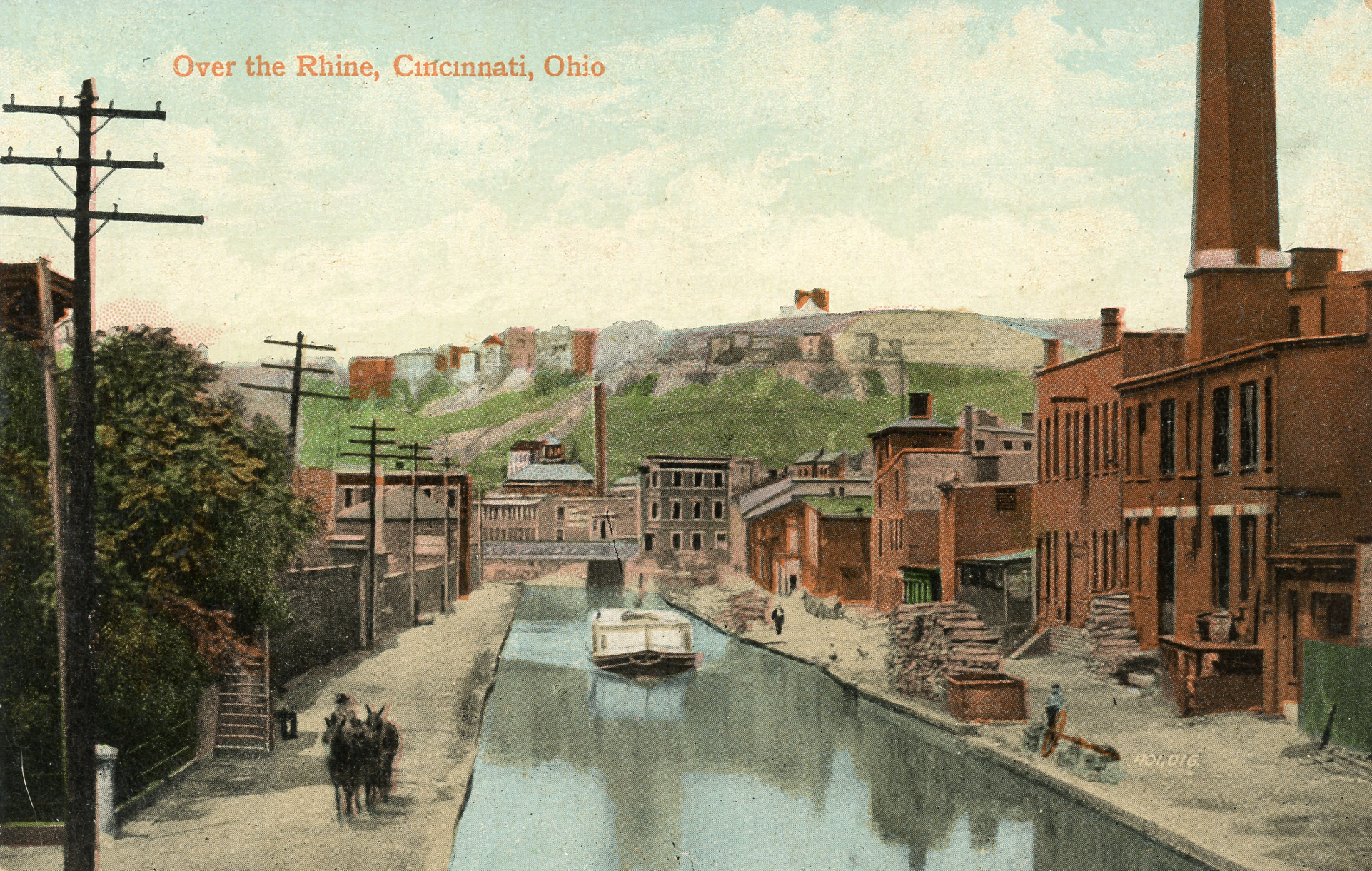

Canals and rivers changed the United States in phenomenal ways. For instance, in 1825 the Erie Canal was completed, connecting the Hudson River at Albany, New York, with Buffalo, New York, on Lake Erie. Merchants and manufacturers of New York City, long the most populous city in the U.S., could then galvanize their trading patterns with the growing Northwest of America, via the Hudson River and the Erie Canal.

The Erie Canal was so influential that other states quickly copied it, beginning a canal-building craze in America that lasted throughout the 1820s and the 1830s. In 1825, construction began on the Miami and Erie Canal, eventually connecting Toledo on Lake Erie with Cincinnati on the Ohio River.

Meanwhile, Kentucky was blessed by many rivers that needed only locks and dams to make them navigable for hundreds of miles. They included the Licking River. In the 1830s, the Commonwealth of Kentucky proposed building 21 locks and dams along the Licking in order to make slack-water navigation possible for 231 miles of the river, up to West Liberty, Kentucky.

Northern Kentuckians and Cincinnatians were excited about the Licking River navigation project. It would make Cincinnati, Covington and Newport merchants and manufacturers highly competitive, able to trade their goods in a vast network stretching south from the interior of Kentucky, then northward along the Miami and Erie Canal, and all the way to Lake Erie.

Hoping for locks and dams

In 1839, Kentucky began construction of the first five locks and dams on the Licking River, meant to enable navigation year-round 51 miles upriver to Falmouth. The timing could not have been worse. In 1837, the nation suffered an economic depression. Further, the state was pouring money into two other lock and dam projects along the Kentucky and Green Rivers.

In 1842, after expending $372,520 on the Licking River navigation project, the state discontinued the construction. None of the first five dams was even begun. Later, some of the stonework of the locks was sold for construction of the John A. Roebling Bridge.

With no operating locks and dams, the Licking River was only navigable during freshets and floods, usually occurring in the Spring and Fall. At those, times, flatboats could carry coal from West Liberty, or felled timber could be tied together as rafts, descending the Licking for Covington, Newport, and Cincinnati markets.

A number of people tried to resurrect the Licking River navigation project, but to no avail. In 1936, the US Congress approved construction of a dam for flood control purposes nine miles above Falmouth. Unfortunately, the dam was never built, and sadly, the Licking River wreaked its havoc year after year, decimating the city of Falmouth in 1997.

Paul A. Tenkotte (tenkottep@nku.edu) is Professor of History and Director of the Center for Public History at NKU. With other well-known regional historians, James C. Claypool and David E. Schroeder, he is a co-editor of the new 450-page Gateway City: Covington, Kentucky, 1815-2015, now available at your local booksellers, the Center for Great Neighborhoods in Covington and online sellers.

For KYCPSJ’s complete seven-part series on the Licking River, from which the KET program was written, follow this link.