Just about every other day it seems that our local news reports on another case of restaurant workers contracting hepatitis A. In fact, multiple restaurants throughout the entire state of Kentucky have been dealing with a severe outbreak and it isn’t going away any time soon.

In accordance with 902 KAR 2:020, cases of acute hepatitis A should be reported within 24 hours. Hepatitis A is caused by a virus that spreads from person to person when they don’t wash their hands. It’s a fecal-oral disease, which means that the virus enters your body through the mouth and is excreted in the feces. Infected people who don’t wash their hands well after using the restroom can easily pass the virus along to whatever or whomever they touch. If they prepare or serve food, they could expose anyone that eats the food.

Symptoms of hepatitis A include fever, fatigue, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, dark urine, clay-colored bowel movements, joint pain, or jaundice (yellowing of the skin or eyes). It can range in severity from a mild illness lasting a few weeks to a severe illness lasting several months.

It is a contagious liver disease that results from infection with the hep A virus, which is a different virus from the viruses that cause hep B or hep C. It is usually spread when a person ingests tiny amounts of fecal matter from contact with objects, food or drinks contaminated by the feces, or stool, of an infected person.

A person can transmit the virus to others up to two weeks before and one week after symptoms appear. The virus can cause illness anytime from two to seven weeks after exposure. If infected, most people will develop symptoms three to four weeks after exposure.

Back in November 2017, the Kentucky Department for Public Health (DPH) identified an outbreak of acute hepatitis A. Since then several cases have been infected with HAV strains genetically linked to outbreaks in California, Utah, and Michigan.

The fact is, five out of the seven states that border Kentucky are in the center of a major hepatitis A outbreak, according to the Center for Disease. Since then, according to the Kentucky Cabinet for Health & Family Services, there have been a total of 3,122 reported cases that have required the hospitalize of 1,576 people of which 19 people have died from this disease, as of Dec. 8, 2018.

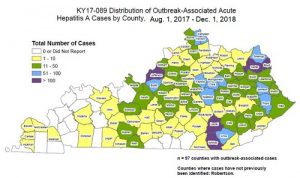

A total of 97 of the 120 counties within the state of Kentucky have had at least one reported case since the outbreak was identified.

It’s been reported that the primary risk factor remains to be illicit drug use and homelessness, and a contaminated food source has not been identified, and transmission is believed to be occurring through person-to-person contact.

Although the CDC has not yet called for mandatory vaccination of foodservice workers, it seems that a large majority of people contracting the hepatitis A virus all seem to work in the restaurant industry.

According to the CDC, the costs associated with hepatitis A are substantial. Between 11 percent and 22 percent of people who have hepatitis A end up being hospitalized. Adults who become ill will lose an average of 27 days of work. Health departments then incur substantial costs in providing post-exposure prophylaxis to an average of 11 contacts per case.

Hepatitis A continues to be one of the most frequently reported, vaccine-preventable diseases in the United States, despite the fact that the FDA approved the hepatitis A vaccine back in 1995.

First responders and healthcare workers are all required to receive the hepatitis A vaccination for obvious reasons. Widespread vaccination of food service employees would substantially lower the spread of hepatitis A infections and reduce the odds of contracting this disease every time we eat out.

There are several factors that weigh into the decision as to why the CDC doesn’t require food service employers to vaccinate their employee’s and it all has to do with the costs. According to the Walgreens website, the hepatitis A series (adult) ages 19+ vaccination costs $113.99 and it is a two-dose series.

Employee turnover in the foodservice industry is extremely high, thus making it impractical to vaccinate an entire restaurant staff when half of them won’t even be employed months later. You just can’t sell that many hamburgers and cokes to offset those reoccurring costs and therefore restaurant management instead enforce good proper hygiene and food handling standards to prevent the spread of this disease.

Emphasis on careful hand washing, use of disposable gloves and not working when ill are measures that can greatly minimize the risk of spreading hepatitis A and a number of other infections.

As a consumer, should you be worried every time you pull through the drive-thru window? I probably would say yes. If you are a germaphobe, I would tell you to race to your local physician and get your vaccination ASAP. If you are like me, the odds are slim but I do plan to ask for my vaccination the next time I go in for my annual physical because I believe in what Benjamin Franklin once said and that is “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.”

Will I stop eating out?

No, because I still “gotta eat” and the food isn’t going to cook itself and deliver itself to me while I am out trying to keep the world safe, or while I am in the office or at home.

Will I avoid those restaurants that recently had a hepatitis A outbreak?

No, because I know that the odds are in my favor if I eat there. I know that once that restaurant re-opens that has been cleaned from top to bottom and just received an exhaustive disinfection, all their employees have been re-trained and everybody that is still employed there is probably washing their hands every 10-15 minutes. That is the place where it is less likely to occur once again. Plus, as a risk management and safety professional, I know that the owner will need his/her loyal customers to not give up on the restaurant because of something he couldn’t control.

Be Safe, My Friends

Keven Moore works in risk management services. He has a bachelor’s degree from University of Kentucky, a master’s from Eastern Kentucky University and 25-plus years of experience in the safety and insurance profession. He is also an expert witness. He lives in Lexington with his family and works out of both Lexington and Northern Kentucky. Keven can be reached at kmoore@roeding.com.