By Paul A. Tenkotte

Special to NKyTribune

Part 74 of the series, “Resilience and Renaissance: Newport, Kentucky, 1795-2020.”

The national economic depression that began in 1873 had far-reaching effects on American cities. In Newport, Kentucky’s case, however, the timing of the depression was worse than for many other municipalities. In 1873, the city had completed its new water works, at a vast cost overrun of nearly $175,000. The resulting debt placed a huge burden on Newport’s municipal finances for years.

By 1874, Newport’s financial condition was far from ideal. In fact, in March of that year, Albert S. Berry, president of the city council, stated “that the interest on the city’s bonded debt now absorbs about half the revenues.” With property tax revenues limited by law for the following three years, the city would need to practice “rigid” economic measures to restore “the confidence of capitalists in the city’s securities” (”Newport, President Berry’s Message,” Cincinnati Daily Gazette, March 28, 1874, p. 3).

Meanwhile, labor movements gained greater momentum in the late 1800s as workers began to organize nationwide strikes. For example, in the late summer of 1877, Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) workers organized a strike in response to their employer instituting a third round of pay cuts. Soon, the strike spread to other railroads, and became known as the Great Railroad Strike of 1877.

The federal government, under the Hayes administration, intervened in the strike, sending US Army troops to assure that B&O passenger and freight trains continued operation. In fact, US General Winfield Scott Hancock (1824-1886) sent General Thomas H. Ruger (1833-1907) to Louisville “to assume immediate control of the troops at that point and [at] Newport” (“National Capital,” Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, July 27, 1877, p. 4).

By July 27th, the Cincinnati Daily Star reported that “two hundred troops” left Louisville for Indianapolis and another “two hundred to Newport Barracks” (Striking Scenes,” Cincinnati Daily Star, July 27, 1877, p. 2). Three days later, on July 30th, the same newspaper reported that all B&O passenger trains in Cincinnati were running on schedule (“Local brevities,” Cincinnati Daily Star, July 30, 1877, p. 5). Nationwide, a combination of US Army troops, National Guard units, municipal police, and railroad security forces defeated the strikers.

In addition to reporting on depression, debt, and disgruntled workers, some area newspapers were also referring to corruption in Newport’s city government. Details, however, were surprisingly sparse. Further, the corruption references were diplomatically written, as if the editors were attempting to avoid libel suits.

Nevertheless, innuendos about corruption were intriguing. For example, in October 1878, the Cincinnati Daily Gazette supported the candidacy of Captain F. A. Stine, an “independent Republican candidate for the office of City Treasurer” of Newport. The Gazette commended Stine for “conducting the campaign on the manly and patriotic basis of anti-corruption,” claiming that he “refuses to break the law by using money to secure his election or influence a vote.” The assumption was clear, namely that Newport’s primarily Democratic city government had its share of influence peddling (“Newport,” Cincinnati Daily Gazette, October 4, 1878, p. 3).

Some of the press went further, pointing fingers at William N. Air. Air was born in Cincinnati, Ohio in August 1834. A steamboat captain, he became the lessee of the Taylor family’s Newport Ferry. He also served on the board of directors of the Newport and Cincinnati Bridge Company, was a racehorse owner, and operated a pavement business. Politically, Air was a Democrat, and served as a city council member representing Newport’s Second Ward. By 1873, the Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, a respected regional newspaper, began calling him “Boss Air,” a reference undoubtedly to the likes of “Boss Tweed” of New York City. Apparently, Air shrugged the term off, reputedly retorting that “every notice we [the Commercial Tribune] give him is worth a hundred dollars to him.” Air died in Newport on February 2, 1907, and was buried in Evergreen Cemetery in neighboring Southgate, Kentucky (“Newport,” Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, December 9,, 1873, p. 3; “Newport,” Cincinnati Daily Star, October 8, 1878, p. 4; FindaGrave)

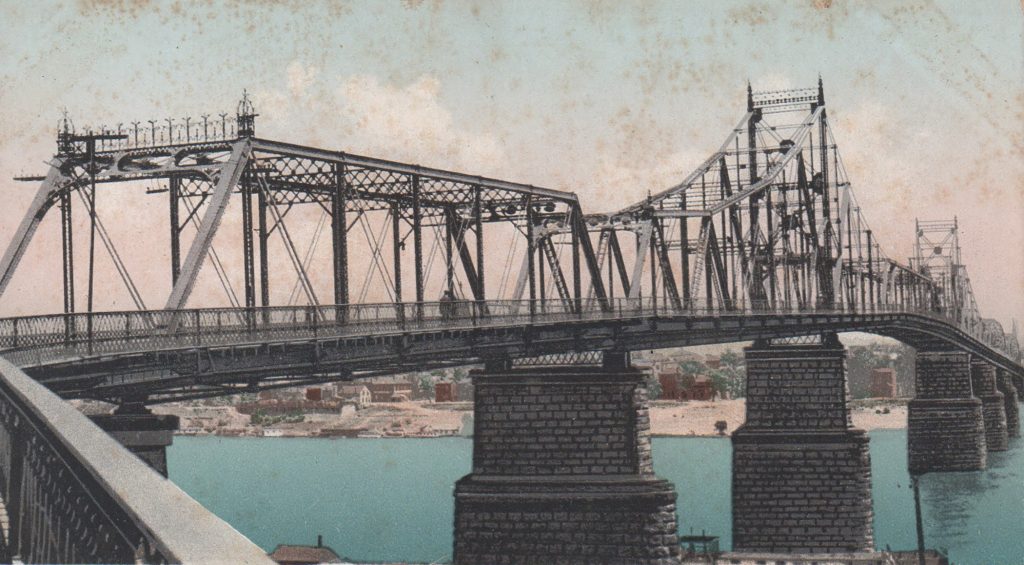

Air, in turn, was a business partner and political ally of Captain John A. Williamson. Williamson was born in Portsmouth, Ohio, on July 9, 1826. When he was very young, his parents moved to Newport. Like Air, Williamson became a steamboat captain. He owned a line of boats operating between Cincinnati and St. Louis. In 1866, he joined Air in a partnership leasing the Newport Ferry. A wealthy and politically astute businessman, Williamson served as president of Newport city council, president of the Newport Light Company, and owner of the Newport Street Railway. His most-well known contribution to Newport, however, was his building of the Central Bridge. The second bridge connecting Newport and Cincinnati, the Central opened in August 1891 (Tenkotte and Claypool, The Encyclopedia of Northern Kentucky; Biographical Cyclopedia of the Commonwealth of Kentucky. Chicago, IL: John M. Gresham Company, 1896).

Air and Williamson were close political associates as well. According to the Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, for instance, when Air was in New York City for business, his candidacy for Newport city council was “generally understood to be in the interests of Captain John A. Williamson’s street railway operations,” a poke at the two men’s weight in city politics (“Newport,” Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, December 13, 1875, p. 6). Williamson died in Newport on July 7, 1898 and was buried in Evergreen Cemetery in Southgate.

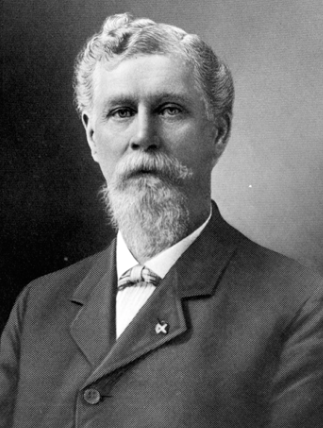

Another important figure in Newport politics was Albert S. Berry, a Democrat known as “The Tall Sycamore of the Licking” (he was 6’5” tall). Born on May 13, 1837 in Jamestown [now Dayton], Kentucky, which was founded by his father, Berry was the scion of two of the pioneer families of Newport, the Taylors and the Berrys. Educated at Miami University of Ohio and the Cincinnati Law School, Berry became an attorney. During the Civil War, he served in the Confederate Army and was promoted to captain. After the war, he married Ann Shaler, daughter of the pioneer Shaler and Southgate families. In 1879, he purchased the Newport Ferry. Berry served as president of the city council of Newport in the 1870s, as a Kentucky state senator (1878-1883), and was an unsuccessful Democratic candidate for governor of Kentucky in 1887. He served in the United States House of Representatives from 1892 until 1902, and was a judge of the Campbell County Circuit Court from 1904 until his death in 1908. He was buried in Evergreen Cemetery in Southgate. (Tenkotte and Claypool, The Encyclopedia of Northern Kentucky; “Judge A. S. Berry Dies after a Brief Illness,” Kentucky Post, January 7, 1908, p. 5; “Judge Berry Passes Away at His Home,” Cincinnati Post, January 7, 1908, p. 8).

The Ohio River floods of 1883 and 1884 did significant damage to Newport. See this NKyTribune history column. Among the many places inundated was the Newport Barracks. Already antiquated and long being considered for closure, the Barracks would eventually move to higher ground in Ft. Thomas in 1894. The Barracks’ old neighborhood, the Licking Bottoms in the city’s low-lying West End, “soldiered on,” but increasingly grew impoverished. In addition, by the early 1900s the neighborhood battled prostitution and other problems. See this history column.

By the 1880s, Newport was also beginning to lose its appeal as a manufacturing city. For example, Dueber Watch Case Company grew discontented with the city and moved to Canton, Ohio. See Our Rich History column. Floods, lack of room to expand, bureaucratic governance, labor difficulties, and competitions from area suburbs and cities gradually turned the tide against Newport’s earlier prosperity.

By the time of Prohibition, Newport already had many demons to duel. Having been pounded by depression, municipal debt, catastrophic floods, and a landlocked city unable to expand very much beyond its boundaries, Newport would face new demons in the twentieth century. As a city reeling from bad timing and natural disasters, Newport saw new opportunities during the era of Prohibition. However, all that glittered was not gold. Organized crime, prostitution and gambling were the costs of disregarding a decades-long need to face Newport’s problems and to build sustainable solutions.

We want to learn more about the history of your business, church, school, or organization in our region (Cincinnati, Northern Kentucky, and along the Ohio River). If you would like to share your rich history with others, please contact the editor of “Our Rich History,” Paul A. Tenkotte, at tenkottep@nku.edu. Paul A. Tenkotte, PhD is Professor of History at Northern Kentucky University (NKU) and the author of many books and articles.

For Part 1 of this Long Depression article, see this NKY History column.