By Sarah Ladd

Kentucky Lantern

Kentucky legislators once again heard arguments in favor of removing the state’s certificate of need requirements for freestanding birth centers during a Monday task force meeting.

The certificate of need requirement mandates regulatory mechanisms for approving major capital expenditures and projects for certain health care facilities, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Sometimes called the “competitor’s veto,” certificate of need (CON) laws were in effect in 35 states and Washington D.C. as of December 2021.

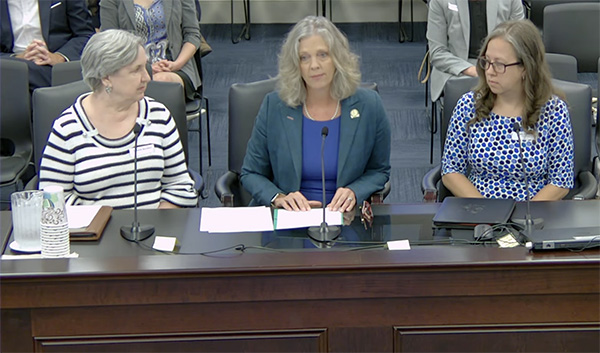

Sen. Shelley Funke Frommeyer, R-Alexandria (center) with Mary Kathryn DeLodder of the Kentucky Birth Coalition (right) and Victoria Burslem, a faculty member at Frontier Nursing University (left) addressed a task force that is studying Kentucky’s certificate of need law. (Screenshot from hearing)

The Certificate of Need Task Force has spent the summer examining Kentucky’s laws with the goal of finding any areas for reform after two Republican-sponsored bills aimed at making freestanding birth centers more accessible failed to advance during the 2023 legislative session.

One of those Republicans, Sen. Shelley Funke Frommeyer of Alexandria, spoke to the task force Monday alongside Mary Kathryn DeLodder of the Kentucky Birth Coalition and Victoria Burslem, a faculty member at Frontier Nursing University, which is based in Versailles and educates nurse-midwives and nurse practitioners across the U.S.

Their appeal for CON laws to exempt freestanding birth centers is based on, among other things, the rising number of home births in Kentucky over the past decades.

Kentucky recorded 177 home births in 1988 and 900 in 2021, Funke Frommeyer said.

“The demand is there” for birthing options outside of hospital walls, she told legislators. “The supply is not.”

Sen. Shelley Funke Frommeyer, R-Alexandria, speaks on removing the certificate of need requirement for freestanding birthing centers, Sept.r 18, 2023. (Photo from LRC)

In 2022, 110 Kentuckians traveled to Tree of Life, a freestanding birthing center in Jeffersonville, Indiana, the Lantern previously reported. That is an increase from 107 in 2021 and 71 in 2020. And, the Clarksville Midwifery practice in Tennessee delivers about 25-30 Kentucky babies every year.

Several lawmakers expressed concern over the safety of giving birth at freestanding birthing facilities, especially in cases of unforeseen medical complications like preeclampsia or uterine rupture.

Birthing centers are only for low-risk births. People with complications or those seeking vaginal birth after a cesarean should deliver in hospitals, Burslem said.

“Certificate of need is about need for a service, not about the safety,” DeLodder said. “Licensure is how our state regulates safety.”

Some argue that weakening or eliminating Kentucky’s CON laws would pull the few money-making opportunities from hospitals, forcing some hospitals, especially in rural areas, to close.

Jaimie Cavanaugh, an attorney with the Institute for Justice, a libertarian public interest law firm based in Arlington, Virginia, disputed a connection between hospital closures and easing certificate of need laws. “We know that certificate of need laws aren’t preventing real hospital closures,” he said.

Katelyn Foust traveled from her Oldham County home to a birthing center in Indiana to give birth to baby Jude. (Provided photo from Kentucky Lantern)

“When we break down (a) reason that we see rural hospitals or other safety net hospitals close or struggle, it often comes down to reimbursement rates,” said Cavanaugh, whose testimony was interrupted by a fire alarm and brief evacuation of the Capitol Annex. “And unfortunately that’s not an issue that certificate of need laws were designed to address.”

Matthew D. Mitchell, a senior research fellow with the Knee Center for the Study of Occupational Regulation at West Virginia University, also testified that the “unusual regulation” that is CON “guarantees a local monopoly.”

“The vast majority of the data suggests CON probably undermines the quality of care,” Mitchell said.

States with CON laws also tend to have higher mortality rates, he said, and patients who aren’t fully satisfied with their care.

“CON behaves pretty much exactly as economists would think it would,” Mitchell said. “It’s a limit on supply, which tends to be associated with higher costs, diminished provision of services and undermines quality.”