By Steve Flairty

NKyTribune columnist

A few weeks ago in this column, I wrote a general profile of Louisville-born, former Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court Louis D. Brandeis, who served from 1916 to 1939.

Though Brandeis graduated from Harvard Law School, he financially supported and gave personal papers to the law school at the University of Louisville in tribute to his native region. Today, that school is named after Brandeis, and he is considered a renowned figure in America’s jurisprudence history as a brilliant, principled, and courageous figure—and the first Jewish person appointed to the Court.

To my pleasure, I found a person in Lexington who has taken a much deeper dive into the life and work of Brandeis. He shares that story as a member of the Kentucky Humanities Speakers Bureau.

I sought to get a closer look at the justice’s life and work, and in the following Q & A, David Miller, of Lexington, gives a studied, nuanced analysis of Brandeis.

Flairty: You have created a Kentucky Humanities Speaker Bureau presentation for Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, Louis D. Brandeis, and the endeavor understandably requires quite a lot of work and passion. Explain the elements of Brandeis’s life that most drew your interest to him.

Miller: I first encountered Louis Brandeis when I was in law school. (Though I practiced law for a while, privately and for the state of Kentucky, I left the profession for a long career with the federal court system instead.) I was fascinated that his name came up in so many different types of cases, and that his work was and is still being debated so many years after his service on the Supreme Court.

The opinions Brandeis wrote, and the dissents he offered when he was on the losing side of a vote, were universally models of clear critical thinking and reflected an effort to consider the actual lives that would be affected by the Court’s decision, rather than relying on airy and imprecise legal tenets inherited from the common law or prior cases.

Brandeis’ point of view was “contrarian” to how law was practiced when he started out, and two particular threads ran through his work. The first was a distrust of the influence of “big business,” which in his day (the early to middle 1900s) meant railroad and energy trusts and big banks, which basically operated as monopolies, against which ordinary citizens had little power. Those monopolies benefited from passive federal and state governments that, in the view of many, were bought and paid for by big-money donors through barely-concealed corruption.

Brandeis’ second major theme was distrust of big government—he (along with an early law partner) developed a theory of a “right of privacy” for ordinary citizens. That right, he argued, was implicit in the Constitution and Bill of Rights and was necessary for citizens to feel free to criticize their government and to keep their private lives to themselves.

The first principle led Brandeis to champion “the little guy” against big-money interests and to help break up the various trusts during the Progressive Era and to regulate banks that gambled, and lost, their depositor’s money. He also helped establish the principle that the federal government had the power to make and enforce child labor and minimum wage laws.

Those powerful corporate interests pushed back hard against such an intrusion on their rights to do business as they saw fit. It took several decades, but eventually Brandeis’ point of view helped bring about the many social reforms pushed through during the Franklin Roosevelt era.

Brandeis’ second principle, that citizens have an inherent “right to be left alone,” developed to deal with burgeoning new technologies such as the automatic camera and the telephone. His view that the government needed a warrant to listen in on private phone calls, for example, reflected his belief that the Bill of Rights demands that a judge consider whether the government has a valid reason to intrude into areas where a citizen can reasonably expect privacy.

It’s not hard to see how this principle is still being debated. His views were initially presented in dissents, but, especially with the expansion of civil rights in the 1950s and 60s (after Brandeis’ death in 1940) it became the dominant view, though the Supreme Court in recent decades has been chipping away at those precedents.

Flairty: Describe a few other luminaries that you think might closely compare to Brandeis, either in the area of jurisprudence or outside that realm?

Miller: In legal circles, a few names come up again and again in widely disparate areas of the law because of their continuing influence on how ordinary Americans live. Some of them in addition to Brandeis include Oliver Wendell Holmes, Benjamin Cardozo, and Earl Warren (because of the Warren’s Court’s expansion of civil liberties, and the Warren Commission’s report on the assassination of John F. Kennedy), as well as environmental and civil-rights champion William O. Douglas.

In more recent decades, high-court names will be remembered for their overruling of many of the civil liberties decisions, including many principles Brandeis and other Progressives fought so hard for.

Brandeis might also be compared to President John Kennedy, who had to overcome significant anti-Catholic prejudice, or Sandra Day O’Connor, the first woman on the Supreme Court, or Thurgood Marshall, the first Black on the Supreme Court. But in reality there’s no one quite like Brandeis in American history.

Flairty: Describe how Brandeis handled the prejudicial pushback toward his Jewish faith, especially regarding his appointment to the Supreme Court.

Miller: Until Brandeis’ nomination to the Supreme Court, hearings in Congress had typically been sedate and quick affairs, most lasting hours at most. Brandeis’ nomination was held up for months because he’d made bitter enemies of some of the country’s wealthiest and most politically-connected men, as well as the enmity of former President William Howard Taft (who wanted the Supreme Court seat for himself).

Brandeis was known as “the people’s lawyer” and the “Robin Hood of the law” for his crusades against big business, and the powerful men pushed back hard, including with a barely disguised ethnic attack against Jews in general. Brandeis himself refused to testify before the congressional committees, but from behind the scenes he ran what was essentially a trial defense against dozens of false accusations. But President Wilson, a Progressive, pushed the nomination through, and Brandeis served on the high court for twenty-three years.

Flairty: Brandeis was a native of Kentucky, though he left the area after his childhood and reached his greatest career heights elsewhere. Explain what foundational aspects of his character and work do you attribute to his upbringing in the state?

Miller: Brandeis grew up in Louisville in the aftermath of the Civil War. For a time, his family, which had immigrated from what is now the Czech Republic, took shelter in Indiana and also moved back to Europe for a few years when Louis was in his late teens.

The family considered themselves secular Jews and didn’t worship often. They highly valued education, instilling a strong sense of social justice and self-improvement in Louis. He took to schoolwork easily and said he received an excellent academic grounding while overseas, so much so that he graduated from Louisville Male High School at the age of 14 with top honors and entered Harvard Law School at 18. He excelled there as well.

For Brandeis, Louisville was always home, and though he didn’t spend much time there later in life he donated his books and official archives to the law school that bears his name at U of L.

He had every opportunity to become a very rich lawyer, to live in a mansion and sail a yacht, but he wanted none of that. Instead, he wanted to live as simply as had in Louisville, in relative quiet, surrounded by books and a loving wife and a few friends, and getting out in nature on a small boat or hiking as often as possible. The strong sense of family and self-reliance, and regard for nature that learned in Louisville kept him grounded and humble as he reached the pinnacle of influence on American jurisprudence.

Flairty: Describe your process in developing the David Miller version of Louis Brandeis, i.e. your research, deciding the slant you would take, and, of course, your props.

Miller: I’d been interested in Brandeis for many years and had read many of his opinions and dissents as well as some of his magazine and journal articles, and there are several excellent biographies of him. The most recent is Louis D. Brandeis: A Life by Melvin Urofsky.

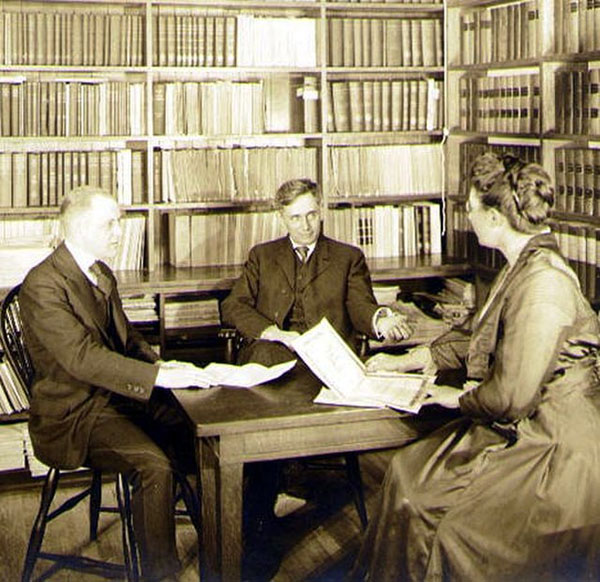

A mental image of Brandeis the jurist was easy to put together from his writings, and writings about him, but I was also curious about Brandeis the man. His many official portraits for the Supreme Court suggest a modest, dignified man, but always seem to capture him with a slight smile, consistent with his reputation as being aloof but confident and intellectually playful. Many historical candid photos online also capture him and his wife enjoying simple hikes and canoe rides around Boston.

From the evidence available, I thought that Brandeis’ quiet confidence, vibrant legal mind, and sly sense of humor might make an interesting Chautauqua presentation, especially if I could make him a “character” through period dress and a plain-spoken but direct and informative script covering the basic of his life and legal influence.

I had a little stage experience when I was younger and have been told I look a little like Brandeis (especially now that my hair is graying) so might be able to pull it off.

I wrote up a one-act play that could be done in thirty to forty-five minutes, whatever length the venue preferred. I was able to find many images online depicting Brandeis’ life from his youth through his final days. The images could be projected through the play to illustrate particular points but weren’t necessary to follow the presentation.

I structured the play as if Brandeis had been granted leave to come back “just this once” to talk about his life and his judicial career, from his early days in Louisville through trust-busting days, his controversial Supreme Court appointment, his support for an independent Jewish state, and his many successes and failures on the bench.

A play needs an antagonist, and I settled on two. The first was easy: J.P. Morgan was one of the richest men in America at the turn of the twentieth century, who controlled much of the country’s banking and railroad wealth. Brandeis’ antitrust work and his helping found institutions like the Federal Reserve earned him the lifelong hatred of Morgan and many other ultra-rich men.

The second antagonist was more personal. Brandeis, along with many other Progressives, favored the “improvement” of the human race through the involuntary sterilization of those deemed “imbecilic” or otherwise undesirable to the American gene pool.

One such case that reached the Supreme Court involved a young woman named Carrie Buck, who was of average intelligence but charged with “loose morals” and was to be sterilized by the state of Virginia. Brandeis and all but one of the eight other justices voted that involuntary sterilization was constitutional. The practice continued, especially in the South, into the 1960s.

Brandeis, who was always supportive of Jewish causes, didn’t live long enough to see the liberation of the World War II concentration camps where so many Jews died of starvation and abuse. Without dwelling on it very long in the presentation, I wondered how Brandeis would handle the fact that his words were cited by the Germans in the Nuremberg Trials, where German officers argued that they were only trying to “improve the race,” as so many Progressives agreed was legitimate.

So, I had two ghosts to haunt Brandeis, J.P. Morgan and Carrie Buck. The first made Brandeis speculate on how we now (in the 2020s) seem to be back in a new era of “too big to fail” banks and all-powerful online social media companies, while Buck made him reconsider what he originally meant by “the right to be left alone.”

My play never got very far. I prepared a five-minute extract and auditioned for the Chautauqua judges. I dressed in my frock coat, vest, string tie, and wire-rim glasses, but wasn’t really that convincing. I didn’t have time to get into any deep issues, and Brandeis remains a name known for a University near Boston and a law school in Louisville, but without the legendary status of a Daniel Boone or Belle Brezing or the countless other colorful characters Kentucky has produced.

I didn’t expect to be chosen for Chautauqua anyway, but it was interesting to put the play together.

I adapted it into a much shorter program, with no costume and little of Morgan and Buck, for the Kentucky Humanities Council’s Speaker’s Bureau. I’m happy to talk about Brandeis, as I think the issues he was most concerned with have re-emerged in our present era, and we could still learn a lot from him.

David Miller can be reached for possible speaking engagements at dtmillerlexky@gmail.com. Also, find his Brandeis blog story written by David at www.davidthurmanmiller.com