By Paul A. Tenkotte, PhD

Special to NKyTribune

New Year’s Day of 1924 in the United States was greeted with cautious optimism. The banner headline of page one of the Cincinnati Post summarized it best: “Roger W. Babson Predicts 1924 Will Be a ‘Fairly Good’ Business Period.”

Business Period,” Cincinnati Post, January 1, 1924, p. 1.

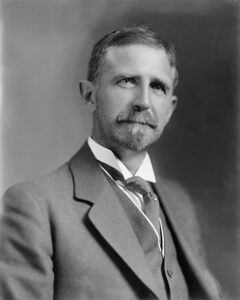

Babson (1875–1967) was a pioneering business statistician and founder of an investment

advisory firm now called Babson-United, Inc. A graduate of the engineering program at MIT (Massachusetts of Technology), he may be considered one of the forerunners of MBA (Masters in Business Administration) programs, which he called “business engineering.”

A proponent of understanding the global economy in a scientific manner, Babson thought that Isaac Newton’s laws of gravity could be applied to the economy, particularly Newton’s third law. That law of motion is sometimes expressed as: “For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.”

Babson was a firm believer that moderation in economic growth was far preferable to the extremes of either boom or panic at either end of the spectrum. In fact, Babson clarified his point by comparing the economy to seasons: “Unfortunately, however, a large proportion of American business men are happy only during a period of boom. They are like the individual who can be comfortable only when it is 80 degrees in the shade” (“Roger W. Babson Predicts 1924 Will Be a ‘Fairly Good’ Business Period,” Cincinnati Post, January 1, 1924, p. 1).

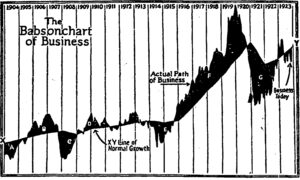

Babson studied the historical vicissitudes of the economic climate. The twentieth-century business cycle seemed to follow his “action and reaction” theory. For example, the US economy boomed in 1906 and early 1907, but then sank into depression throughout 1908. It then rebounded until 1914, followed by a short recession. United States’ entry into World War I in 1917 led to boom times. Of course, what goes up inevitably must come down in Babson’s Newtonian economic world. By 1921–1922, the economy had dipped again. Then, in 1923, it began to rebound.

Babson emphasized that boom times were usually accompanied by “rising commodity prices and speculative profits” that would inevitably lead to an economic bust. “Excessive prosperity, like very hot weather, saps our vitality, inflates our currency and drives prices out of all proportions to true values. Such a period encourages speculation rather than honest effort and upsets our sense of value and the true proportion of things.” The result was economic depression, which he declared “discourages men and wrecks businesses that have been a lifetime in the building. Its costs are written not only in dollars but in hunger, in want and in human suffering.”

Babson also noted that economic cycles corresponded to the political climate. He alleged that historical evidence demonstrated that “business has a decided effect upon the elections. Whenever we have chosen a president during a period of business depression, we have usually changed parties. If the election has fallen during a period of business prosperity, we have usually kept the previous administration in office.”

The year 1924 would feature a presidential election. In fact, only five months before New Years’ Day of 1924, President Warren G. Harding (Republican) had died of a heart attack. Vice President Calvin Coolidge (Republican) served the remainder of the Harding presidency, and then was reelected on his own ticket in 1924.

Although Coolidge had “supported many progressive pieces of legislation” as former governor of Massachusetts, he was an advocate of federalism in government, that is, “distinct yet equal spheres between the federal government and its powers” and those at the state level. As a result, Coolidge “believed that regulating business and agriculture was not a federal responsibility but belonged to state and local governments” (Paul A. Tenkotte, United States History since 1865: Information Literacy and Critical Thinking Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt Publishing, 2022, pp. 172-173).

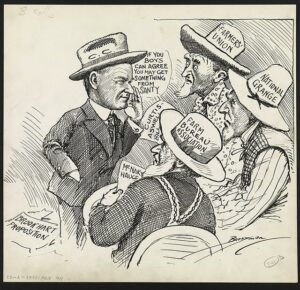

The Evening Star (Washington, DC) on November 12, 1927. It satirized Coolidge’s lukewarm support of American farmers, as well as the inability of American farmers to coordinate their efforts to achieve effective political change. (Library of Congress)

Although the American economy generally prospered throughout the “roaring twenties,” systemic problems remained. Farmers in the United States “found themselves saddled with more land than they needed, new costly mechanization, and more debt than they could afford.” Meanwhile, higher American tariffs intended to protect American industry “meant that Europeans would sell fewer goods to Americans, which in, in turn, translated into Europeans having less money to buy American-made goods and to repay their debts.” For American farmers, “the situation was especially distressing, as Europeans likewise raised tariffs, further reducing their purchase of American farm products” (Tenkotte, p. 173).

Coupled by reckless speculation in the stock market, the bubble would burst in 1929, sinking the United States — and the world — into the Great Depression. Had Babson’s understanding of the business cycle in 1924 and his accompanying cautions been heeded, perhaps the 1929 slide into the world’s widest and deepest economic depression might have been less precipitous and more short-lived.

Paul A. Tenkotte, PhD is Editor of the “Our Rich History” weekly series and Professor of History and Gender Studies at Northern Kentucky University (NKU). He also serves as Director of the ORVILLE Project (Ohio River Valley Innovation Library and Learning Enrichment), premiering in Summer 2024. ORVILLE is now recruiting authors and documentarians on all aspects of innovation in the Ohio River Watershed including: Cincinnati (OH) and Northern Kentucky; Ashland, Lexington, Louisville, Maysville, Owensboro and Paducah (KY); Columbus, Dayton, Marietta, Portsmouth, and Steubenville (OH); Evansville, Madison and Indianapolis (IN), Pittsburgh (PA), Charleston, Huntington, Parkersburg, and Wheeling (WV), Cairo (IL), and Chattanooga, Knoxville, and Nashville (TN). If you would like to be involved in ORVILLE, please contact Paul Tenkotte at tenkottep@nku.edu.