By David Childs, PhD

Special to NKyTribune

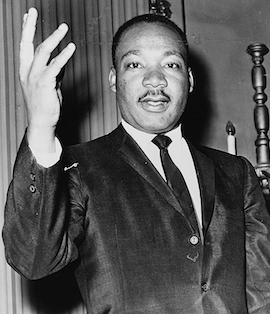

“I have the audacity to believe that people everywhere can have three meals a day for their bodies,

education and culture for their minds, and dignity, equality, and freedom for their spirits.”

– Martin Luther King, Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech, 1964

Did the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. enjoy the same level of popularity in his time that he

does today? Consider the quote above, as it goes beyond racial equality to the broader, less popular

topics of more economic equality and human rights. These ideas made him unpopular in many

circles. Many people today would not have supported him when he was alive, as they would have

deemed him too radical. Some of the contemporary tributes to King fail to take an in-depth analysis of

his more complex and sophisticated ideas. When one delves deeper into his work, one discovers that he

spoke a lot about more broad democratic principles such as justice, freedom, equality, fairness and

creating what he called the “beloved community.”

But what about King’s lesser-known ideas, some of which may be useful tools in addressing social and political challenges of contemporary times? In his time, Dr. King was vilified, persecuted, and eventually murdered because his ideas challenged the status quo and the established order. Stephen and Paul Kendrick, in an April 3, 2018 Washington Post op-ed article, wrote “In our long effort to

moderate King, to make him safe, we have forgotten how unpopular he had become by 1968. In his last years, King was harassed, dismissed and often saddened. These years after Selma are often dealt with in a narrative rush toward martyrdom, highlighting his weariness. But what is missed is his resilience under despair. It was when his plans faltered under duress that something essential emerged. The final period of King’s life may be exactly what we need to recall, bringing lessons from that time of turmoil to our time of disillusion.” Right up until the day that he died, King had many critics, but after he was killed people celebrated and praised him. A Newsweek article from January 15, 2018 published a 1966 Gallup Poll showing that he was not supported by the majority of Americans and was quite discouraged before he passed.

Dr. King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” is a good source to draw from when discussing King’s critics. Martin chose to go into the ministry after first considering being a medical doctor or lawyer. In his writings, he states that the church and his role as a minister gave him the best resources and platform to answer “an inner urge to serve humanity.” In the letter he directly addresses his fellow clergy, who were very critical of his work. He begins by stating “while confined here in the Birmingham city jail, I came across your recent statement calling my present activities unwise and untimely.” He goes on to write that he normally does not address many of his critics but feels that since “. . . you are men of genuine good will and that your criticisms are sincerely set forth, I want to try to answer your statement in what I hope will be patient and reasonable terms.” King took it to heart that much of the disapproval came from his colleagues in the ministry, who he believed — of all people — should understand his perspective. To be fair, King enjoyed immense popularity among many people, but he had just as many enemies as he had admirers, if not more.

One of the principles King is most noted for was his practice of nonviolent resistance. However, it is not common knowledge that he did not always subscribe to nonviolence and early on believed in self-defense. King had even purchased firearms to protect his family from attackers in his home. He later spoke out against self-defense, but many of his associates carried firearms to protect him. Through his readings and affiliations, he came to strongly and publicly denounce the personal use of guns. His advisers showed him an alternative to violence and how nonviolent resistance can act as a powerful tool. The goal was not to humiliate one’s opponent but to win them over as a friend. He adopted this idea because it was consistent with his religious beliefs as a Christian and a Baptist minister. Two of King’s primary advisers were Christian theologian Howard Thurman and white activist Harris Wofford, from the Christian pacifist tradition. Another one of King’s key mentors was veteran African-American civil rights activist Bayard Rustin, who helped coach and train him in strategies of nonviolent resistance.

Both Wofford and Rustin had studied Gandhi’s teachings and exposed King to his philosophies. In King’s

early activism in the 1950’s, he rarely used the term “nonviolence” and knew very little about Gandhi’s work.

When one hears excerpts from King’s popular “I Have a Dream” speech, it is often heard starting from the climax toward the end of the sermon. The speech is played from the part that repeats “I have a dream.” We hear Dr. King begin this segment with the lines “I say to you today, my friends, so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal.’”

on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. (Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History

and Culture)

Even though these words are electrifying and speak of high moral ideals, we often miss equally deep and powerful concepts discussed earlier in the speech. For example, King stated: “Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy. Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. Now is the time to lift our nation from the quicksands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood. Now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God’s children.” Even though these words were spoken in 1963 it applies to our time period as if it were written for today. There has long been the popular notion that America has moved well past the injustices and racial prejudices of the Civil Rights era, however with the rise of hate groups, white supremacy, discriminatory housing and hiring practices, and racial violence in the US, it seems that the nation has regressed. Indeed, the line “Now is the time to lift our nation from the quicksands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood” can be applied to today as the US becomes more and more divided along racial lines.

King’s “I Have a Dream Speech” speech reminds us that racial injustice can act as quicksand that can impede progress in our land. It can cause us to be stuck. King’s legacy challenges us to lift our nation up toward a more just society. He echoed those sentiments in that same speech when he stated that he would not be satisfied “until justice rolls down like water and righteousness like a mighty stream.” We need that justice right now as we see an alarming rise of injustice across the nation.

This is a revised and updated version of an article that was originally published January 24, 2019 entitled “Martin’s Ideas: A More In-Depth Look at Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.” in Democracy and Me a Cincinnati Public Radio program.

David Childs, Ph.D., has been a member of the social studies and history faculty at Northern Kentucky University since 2012. He was the first African American in the College of Education to earn tenure at NKU. He is an undergraduate of Mount Saint Joseph University, holds two master’s degrees, and earned his doctorate at Miami University of Ohio in African American history, educational leadership and philosophy, as well as an honorary doctorate in theological studies from Temple Bible College and Seminary in Cincinnati. He is the co-author of the book, Escaping from Home, a novel about slavery and freedom, available from Amazon. He is director of Black Studies at NKU, where he and fellow professors and students are presenting a research study at the Smithsonian on the role the Ohio River played in slavery and the Underground Railroad.

Paul A. Tenkotte, PhD is Editor of the “Our Rich History” weekly series and Professor of History and Gender Studies at Northern Kentucky University (NKU). He also serves as Director of the ORVILLE Project (Ohio River Valley Innovation Library and Learning Enrichment), premiering in Summer 2024. ORVILLE is now recruiting authors and documentarians on all aspects of innovation in the Ohio River Watershed including: Cincinnati (OH) and Northern Kentucky; Ashland, Lexington, Louisville, Maysville, Owensboro and Paducah (KY); Columbus, Dayton, Marietta, Portsmouth, and Steubenville (OH); Evansville, Madison and Indianapolis (IN), Pittsburgh (PA), Charleston, Huntington, Parkersburg, and Wheeling (WV), Cairo (IL), and Chattanooga, Knoxville, and Nashville (TN). If you would like to be involved in ORVILLE, please contact Paul Tenkotte at tenkottep@nky.edu .