The theme for December’s Northern Kentucky Sports Hall of Fame inductions was simple: Family.

Three of them were actual family, the Bergers – brothers Dick, Chuck and Jimmie – with a coach of one of them – Hep Cronin – talking of his first home six houses down from the Bergers on Pleasant Ridge in Ft. Mitchell. Dr. Ray Hebert talked specifically of family – and after 50 years teaching at Thomas More, the New Englander is certainly family. And the final one, the late peewee football coaching legend, Harlan Strong of Erlanger-Elsmere, turned those two communities into a family unlike any other in Northern Kentucky at the time.

The large crowd – maybe largest ever for a monthly induction get-together – at The Arbors in Park Hills, could not have enjoyed the combined Christmas party and inductions more.

Dr. Ray Hebert: Start with Dr. Hebert, a multi-sport athlete in his native New Hampshire, who knew he was in the right place when his interview for a history faculty position at Thomas More included this final question: “So you’re a shortstop,” they wanted to know, “we need a shortstop.” And while his wife, a New York City native said she guessed they’d be here “three to five years,” that number is now 50 for the published author of books on the history of TMU and sports at TMU.

“Sports has taught me the value of family – in New Hampshire and here,” Ray says. “I was able to coach my daughters and grandson thanks to the two great loves of my life – sports and family.” And then there’s his additional love – “Thomas More,” Hebert said of his career as a full professor of history and Dean Emeritus of the college.

He’s executive director of the William T. Robinson III Institute of Religious Liberty and played years of active softball from the 1970s through the 1990s here.

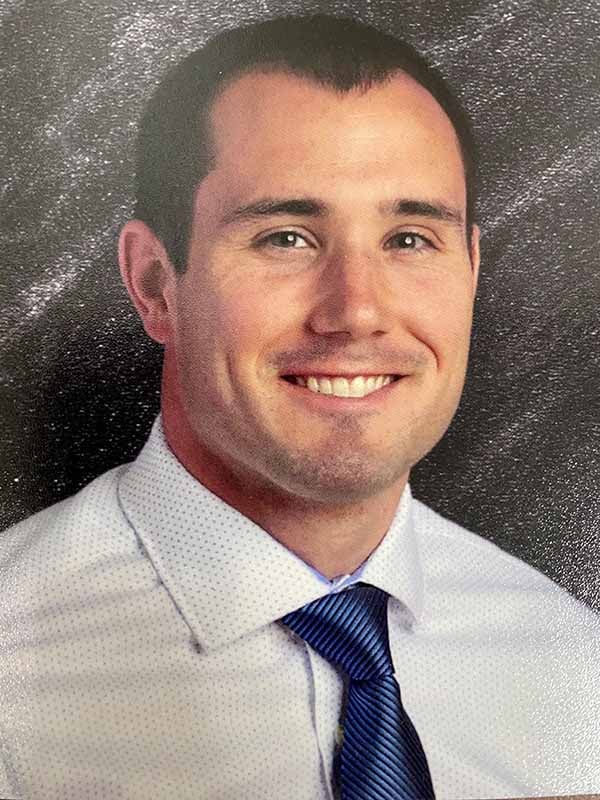

Harold “Hep” Cronin explained the honor for him as only this smart handicapper could: “I hit the Trifecta,” the Cincinnati native and former Covington Catholic coach said after earlier inductions into the Hamilton County and Greater Cincinnati sports halls of fame. “What are you being inducted for?” his son, Mick Cronin, the basketball coach at UCLA was asking him the other day. After all, Hep a star athlete at Cincinnati’s Hughes High had grown up in Corryville near the UC campus where he would be a freshman basketball teammate of Oscar Robertson. While at Hughes, Hep, who would go on to play middle infield for Hamilton Tailoring’s two world’s champion softball teams after having been named all-city first-team second baseman. The second-team all-city second baseman that year? Pete Rose, who would later play on Hep’s 6-foot-and-under basketball team.

A two-time All-Missouri Valley Conference baseball player, Hep heard from the head of CovCath’s boosters club after his UC graduation and was told there’d be a teaching/baseball/basketball coaching job for the 21-year-old. “Now we have to find a teaching spot for you,” CovCath Principal Bro. Don McKee told him in the interview. But the three subjects CovCath had open were not in Hep’s wheelhouse. So he ended up teaching typing. “I can’t type,” Hep confessed to Bro. Don. Didn’t matter. He had the job and “I must have done well,” Hep said, they asked me to teach it in summer school. Hep said his top quality was honesty. He’d start each class on Day 1 with this line: “You don’t know how to type and neither do I,” he said with a glance at his old school next door, “that was 60-65 years ago.”

Hep, as the middle man in the coaching triumvirate of head coach Mote Hils and freshman coach Ralph Bogenschutz, would soon embark on a journey of unparalleled success with five straight Ninth Region titles, the only time that’s ever happened here.

Then it was off to more success in Cincinnati as head coach at Roger Bacon and Oak Hills, where Hep was named Coach of the Year in Cincinnati and LaSalle, where his team won an Ohio State championship. On top of that, Hep became a highly respected Atlanta Braves baseball scout. One quick story: Hep convinced the Braves director of scouting to fly up for the last two games in David Justice’s Thomas More career. Completely overlooked because his high school, Covington Latin didn’t have a baseball team where he’d skipped two years and was an 18-year-old collegian, Justice could be a steal in the draft.

Another Hall of Famer, umpire Ron Bertsch, was behind the plate that day, Hep wanted to make sure his boss got to see Justice hit. So they made a deal. No walks. Bertsch went along although some of the pitches he had to call strikes to give Justice a chance to hit were just inches off the ground. But hit Justice did, with a couple of 400-foot home runs in a nine-for-12 day that got him moved up to the fourth round (he’d be a first-rounder today, Hep says) with a $30,000 signing bonus (a million dollars today) and on his way to a 14-year major league career, two World Series wins (Braves and Yankees), rookie of the year honors and three selections as an all-star.

When he got the call from NKSHOF President Randy Marsh, Hep was wondering “What the heck does he want with me?” and thinking of the young man telling him one day he wouldn’t be seeing him any more doing high school games because he was heading to umpire’s school in Florida. And then in a Game 7, ninth-inning play at the plate to win the National League pennant in 1992 for the Braves, Sid Bream barely beat the throw, with the man making the safe call at the plate none other than Randy Marsh. The other man in what has become a famous baseball photo? Justice, who scored in front of Bream and was leaping on him in celebration.

More proof of “how life goes in cycles,” Hep said, pointing toward CovCath next door where it all started for him. “That was 60-65 years ago,” Hep said.

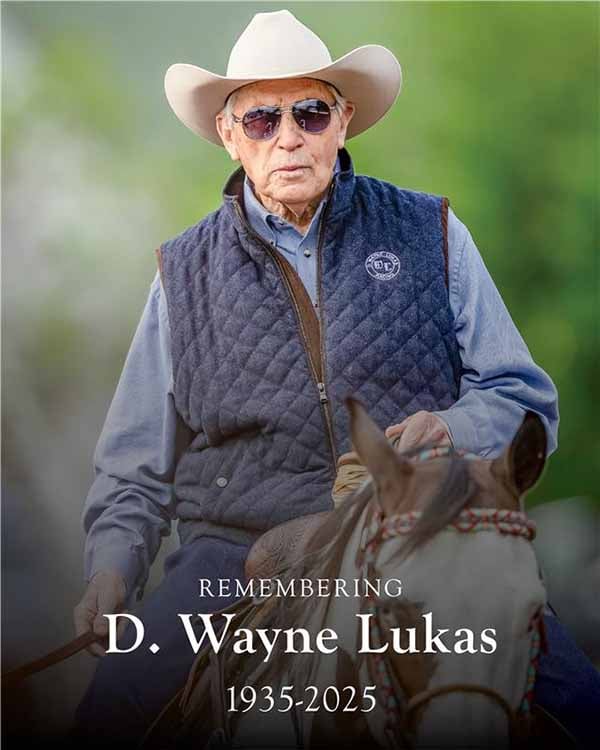

Harlan Strong: Most of the folks associated with the Hall of Fame just assumed that Strong, the legendary youth football coach who founded the Erlanger Lions program in 1957, soon after his graduation from Lloyd Memorial High School, must have already been a Hall of Famer. But he wasn’t. And now, just weeks after the discovery, with a strong push from his former players Jon Long, Milton Johnson, Billy Lewis, Robert Lett, Dave Pickett, Sam Dinn and John Bain, he is.

Harlan put together 20 years of winning programs and a team voted No. 3 in the nation one year and took his Lions to bowl games in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Maryland and Texas. But after dying of a heart attack at the age of 55 in 1995, his wife, Brenda, said “he’s watching down from his spot as an angel in heaven where he and many of his friends are celebrating.”

One thing to be celebrating was Strong’s ability, in a Northern Kentucky with little racial diversity as the schools were just starting to desegregate, was that in the Erlanger-Elsmere community, the role of the Erlanger Lions football team was extremely important. That’s the conclusion of Lloyd alum and local historian Carol Whitson Kirkwood, after talking to many of Strong’s players through those years. “Youth sports offered a way for black and white families to become more familiar with each other socially,” Lett said. “An unintended consequence, to be sure, but a real one, nonetheless,” said Kirkwood about Lett’s remarks. A member of the first fully integrated class at Lloyd. Lett’s father was the principal at Covington Grant. “He (Strong) was the first white person of authority who saw them as just kids and related how much it meant to them to be included on those teams,” Kirkwood says.

Interestingly, the white players on those teams didn’t think of their time together as anything special, just the natural way of things, which would have been another tribute to how well Harlan handled this. The Lions program was the community coming together the way it should be.

The Berger Brothers: Chuck was the middle brother, the one of whom younger brother Jimmie says, “I miss him very much, Chuck would have been so proud.” But Chuck, built like a linebacker, with the defensive ability to play like one, didn’t want to give up basketball, a sport he played so well for four years at CovCath and the first four years of NKU’s college basketball history where he started and played all four years for Mote Hils, his coach at CovCath.

At 6-feet-2, Chuck could guard anybody. One game in particular I’ll never forget. NKU was in Nashville at a nationally ranked Tennessee State featuring one Leonard “Truck” Robinson, the nation’s top college division player as a 6-7, 225-pound rugged post guy who would go on to an 11-year NBA career where he would become All-NBA first teamer and lead the league in four categories. Chuck held him to seven points.

How good a football player Chuck would be, we’ll never know. As a CovCath football assistant, I was unable to convince the Bergers’ mom, Maydie, the most supportive parent anyone could ever hope for, that football would be safe. And Chuck, who died in 2020 at the age of 66, could still play basketball.

“She saw all three brothers play in the Ashland Invitational Tournament,” Jimmie said of the 50-year anniversary of his mother’s Dec. 31 death, “and five days later she was dead.”

“She was always there for us,” said Dick, a Vietnam vet who got things going for the brothers as a member of the 1967 CovCath team that lost the state championship to Earlington on a shot with six seconds left. “I was a member of the best team,” said Dick, who played baseball and basketball all four years at CovCath, “although my brothers won’t agree.” Chuck’s 1971 team is certainly a candidate for that honor. “We had a bunch of guys who really got along. It was a great time to be at CovCath. If you weren’t there by 6, you wouldn’t get in,” he said of the sold-out crowds.

Jimmie came along nine years after Dick and started three years in both baseball and basketball at CovCath, where he averaged 12 points a game in basketball for his career and played four positions in baseball – pitcher, catcher, first base and outfield.

“Jimmie gave us everything he had,” said his basketball coach, Dick Maile, noting that Jimmie’s 42-0 Blessed Sacrament grade school team was the best he’s ever seen. “It’s a real honor for my brothers and me to be included with such athletes,” Jimmie said.

But a broken foot kept him from becoming a 1,000-point scorer at CovCath and left him with something his baseball coach George Schneider told him when he stopped by his office to let him know about the injury.

“You’re here today because God has something more important for you tomorrow,” Jimmie said of the words that have stayed with him all those years ago. All three brothers have worked together in the family’s Bilz Insurance.

Contact Dan Weber at dweber3440@aol.com. Follow him on X, formerly Twitter, @dweber3440.