By Paul A. Tenkotte, PhD

Special to NKyTribune

In celebration of Women’s History Month

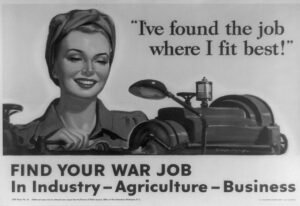

By the late 1940s, women across the United States and Northern Kentucky found themselves reverting to traditional roles within the home, as returning American servicemen replaced them in the labor market. During World War II, the U.S. government had encouraged women to enter the workplace, assuring that manufacturing and service sectors successfully converted from consumer to wartime production.

In fact, by 1944 more than nineteen million women, or 37% of adult women, held jobs outside the home. American military success relied heavily upon their work. The United States produced a phenomenal record of “296,429 airplanes; 102,351 tanks and self-propelled guns; 372,431 artillery pieces; 47 million tons of artillery ammunition; 87,620 warships; and 44 billion rounds of small-arms ammunition” for the war effort (Penny Coleman, Rosie the Riveter: Women Working on the Home Front in World War II. New York: Crown Publishers, 1995, p. 19)

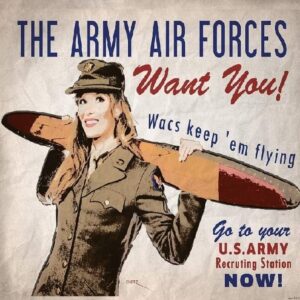

In some sectors of the economy, women continued to explore educational and employment opportunities in the postwar era. For instance, in 1950 the U.S. Army (USA) and the separate, newly formed U.S. Air Force (USAF, 1947) were recruiting women at their Covington office in the downtown U.S. Post Office. Maj. Walter E. Flagg, “commanding office of the Cincinnati recruiting station,” recalled how the service of women during World War II revealed that they “could master highly technical subjects with ease.” Flagg added that “Women also are particularly well suited to certain administrative jobs.” He promised that new women recruits would be trained as specialists. According to the Kentucky Post, some of the fields open to women in the USA and the USAF were “Medicine, communications, public relations, physical sciences, photography, drafting, radio, personnel work, mechanical trades, administration, statistics, finance, weather, aviation supply, [and] food service among others” (“Army, Air Force Recruiting Women,” Kentucky Post, October 26, 1950, p. 10).

Nevertheless, women in the workforce remained a controversial issue in the 1950s. In January 1950, the Kentucky Post announced that the Latonia Literary and Music Club would be holding a debate at St. Mark Evangelical Church in the Latonia neighborhood of Covington. The reporter predicted that the event was “designed to provoke a heated discussion.” The debate centered around two different viewpoints of the following statement, namely that “the emergence of women from the home is a regrettable feature of modern life.” Mrs. Harry Gaynor, Mrs. G. W. Ledford, and Mrs. E. H. Leegan were scheduled to speak “for the affirmative side of the question,” while Mrs. Sharon Florer, Mrs. Lytle Henrickson and Mrs. Eugene McKinley were slated for the “opposing side.” How the debate went is unknown, as there appears to have been no follow-up article (“Emergence of Women from Home to be Debated,” Kentucky Post, January 11, 1950, p. 4).

During World War II, the production of automobiles as well as most new construction was halted. Factories converted from consumer goods to wartime materiel. Housing was “limited and expensive. Plus, Americans had been frugal throughout the war, saving about $30 billion.” Consequently, there was a great deal of pent-up demand to buy consumer goods (Paul Tenkotte, United States History since 1865: Information Literacy and Critical Thinking. Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt Publishing, 2022, p. 214).

In the postwar era, women would play a prominent role in this new consumer economy. Ironically, however, married women still lacked the opportunity to obtain loans or credit cards on their own behalf. Likewise, women were also prohibited from joining many of the all-male community organizations, such as Optimist International, founded in Louisville in 1919. In response, women began organizing their own all-female chapters of the Optimists, called “Opti-Mrs.” clubs.

The Covington Opti-Mrs. Club was founded in October 1937, holding its first luncheon at the Covington Chamber of Commerce. Margaret Arnim, the Kentucky Post’s Society Editor, described the organization as being composed of “wives of members of the Covington Optimist Club.” Mrs. Fred Macklin served as its first president. Already by June 1938, they had founded an Opti-Mrs. Girls’ Club for “underprivileged girls in Covington.” Several months later, they opened a girls’ clubhouse at 216 W. Third Street in Covington, providing “a wholesome atmosphere where young girls may pass their leisure time” (Margaret Arnim, “Members of Art Club are Carried back to ‘McGuffey School Days,” Kentucky Post, October 12, 1937, p. 2; “Need Furniture for Girls’ Club under OptiMrs.,” Kentucky Post, June 6, 1938, p. 4, “Open House and Tea on the Calendar for Opti-Mrs. Girls’ Club,” Kentucky Post, September 23, 1938, p. 10).

In 1947, another Northern Kentucky chapter of the Opti-Mrs. Club was founded in conjunction with the newly established Dixie Optimist club. Both served the Dixie Highway suburbs west of Covington. Underscoring women’s roles in the new consumer economy, the Dixie Opti-Mrs. Club met at the Hearthstone Restaurant in Fort Mitchell for its regular luncheon in November 1949. Mrs. Howard Bary, chair of the American Home Department of the Kentucky Federation of Women’s Clubs, was the featured speaker. She explained “the important part played by women in the economic world inasmuch as they spent 85 per cent of the nation’s income.” However, while she encouraged “clubwomen to become more active and to develop a new awareness of community, national and international affairs,” she did so “as a means of improving the American home” (“Donations Voted by Opti-Mrs.: Dixie Club Hears Kentucky Federation Officer Speak,” Kentucky Post, November 4, 1949, p. 11).

Limited opportunities were available for Northern Kentucky women at some traditionally oriented men’s non-profit institutions. Although Covington did not have its own separate YWCA (Young Women’s Christian Association), the Covington YMCA (Young Men’s Christian Association) had a “director of women and girls,” Miss Martha Bunch. The Covington “Y” featured activities for women, for example “learn-to-swim” classes for “girls eight years old and older,” as well as separate swim lessons sessions for adult women (“Registration Set for Girls, Women at ‘Y,” Kentucky Post, June 13, 1950, p. 5).

In Northern Kentucky, the postwar economy proved strong. It consisted of manufacturing, service industries, and—illegal gambling. While Newport was the centerpiece of gambling and prostitution, suburban cities throughout the area were also complicit. Generally, Northern Kentucky was a wide-open place, where you could find whatever your heart desired and whatever your pocketbook afforded. By January 1949 the Kentucky Post reported that “organized prostitution” had “mushroomed in recent months in Newport into an expansive operation of a dozen or more establishments” (“Judge, Prosecutor Pledge Co-operation in Full Investigation,” Kentucky Post, January 19, 1949, p. 1).

Of course, illegal gambling and prostitution were paradoxical to the averred standards of married and family life of the late 1940s and the 1950s. So too were “quick marriages.” Like later Las Vegas, Northern Kentucky was a place where you could go for a “quick marriage,” twenty-four hours per day, seven days a week. By 1949, according to the Kentucky Post, “Thousands of out-of-town couples visit northern Kentucky each year to be married.” To make matters worse, so-called “marriage touts” preyed upon young couples in cars possibly in search of quick marriages. Rival Covington and Newport touts were even invading one another’s territories. The touts stopped “autos bearing out-of-town license plates and containing persons who appear to be looking for a place to obtain a marriage license.” Then, a reporter described how the “touts tell the couple that for a ‘fee’ they will take them to a doctor where they can obtain the required blood text in a short time and then to a place where they can be married without delay” (“War among Marriage Touts Reported: Newport Men Moving over to Covington,” Kentucky Post, January 19, 1949, p. 1).

The marriage touts included taxicab drivers, three of whom were arrested among six people in an April 1949 Covington raid. Prosecution of the arrested marriage touts would often prove difficult, as out-of-town couples were reluctant to testify in court. Besides sometimes functioning as marriage touts, taxicab drivers were also known to take customers to houses of prostitution, where they earned a finder’s fee. (“6 Arrested in War on Marriage Touts,” Kentucky Post, April 16, 1949, p. 1; “Marriage Tout Suspects Win Dismissal,” Kentucky Post, April 26, 1949, p. 1; “Marriage Law Fight Pledged by Churchmen,” Kentucky Post, December 16, 1949, p. 1).

Fortunately, Kentucky’s quick marriages were scheduled to become illegal. In 1948 the biennial Kentucky General Assembly had revised the state’s marriage code, effective January 1950, to read that “No county clerk shall issue a marriage license until the application for a marriage license remains on file, open to the public, in the office of the county clerk for three days before the license is issued.” Interestingly, W. Sharon Florer, the secretary of the Kenton County Protestant Association and husband of one of the debaters at the Latonia Literary and Music Club event, helped to write the 1948 legislation. It was heralded through the Kentucky Senate by Covington senator, Sylvester Wagner, and through the house by its speaker, Rev. T. Herbert of Warsaw in Northern Kentucky (“Bitter Battle Seen Today on Marriage Law,” Kentucky Post, February 27, 1948, p. 1; Marriage Wait Bill, Mutuel Tax Passed,” Kentucky Post, March 18, 1948, p. 1).

While the role of women in the workforce was restricted in the postwar era, they nevertheless made great strides to further advance their professionalism. The Opti-Mrs. clubs in Northern Kentucky were a clear sign that women desired a greater involvement in postwar society. However, women were still far from attaining access to educational and employment opportunities afforded to males.

Paul A. Tenkotte, PhD is Editor of the “Our Rich History” weekly series and Professor of History at Northern Kentucky University (NKU). He can be contacted at tenkottep@nku.edu. Tenkotte also serves as Director of the ORVILLE Project (Ohio River Valley Innovation Library and Learning Enrichment). For more information see https://orvillelearning.org/