By Paul A. Tenkotte, PhD

Special to NKyTribune

Ashes on foreheads on Ash Wednesday, “fish frys” on Fridays, passion plays, and the annual “Praying the Steps” on Good Friday at Holy Cross-Immaculata Catholic Church on Mt. Adams in Cincinnati — all these evoke vivid images of Lent. In Christianity, Lent is the 40-day season between Ash Wednesday and Easter Sunday. It is a time of reflection, forgiveness, and reconciliation, a recollection of the biblical account of Jesus Christ fasting 40 days in the desert. In the Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky region, where Catholic, Episcopal, Lutheran, and other Christian denominations predominate, Lent is still observed today with age-old traditions.

Having attended twelve years of Catholic elementary and high schools, four years of Catholic college, and having taught twenty-two years fulltime at a Catholic college (Thomas More University), floods of Lenten memories fill my mind. I can literally “smell” Lent—from liturgical incense to the frying of fish. Abstinence from meat on Ash Wednesday and on all Fridays of Lent marked my passage as a Catholic boy born in the early days of Vatican II, after stricter Lenten obligations had been reduced. I loved my mother’s Lenten dinners. My favorite was canned tuna (my dad and I preferred to add a little vinegar), peas, and scrambled eggs. I also liked fish and chips (French fries). For lunches, there were packed peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, or fried cod in the school cafeteria, both of which were delicious.

In the 1960s and 1970s, some regional public schools even served fish on Fridays (sometimes year-round) in their school cafeterias. Not long ago, my friend John admitted that he and many of the other Protestant students at their public school in Miamisburg, Ohio regarded fish on Fridays as a treat. As a youngster, John once commented to a classmate, “I can’t wait for lunch. They’re having fish again. I wonder why they always have fish on Fridays.” His friend solved the puzzle: “It’s for the Catholic kids.”

“Fish frys” on Friday evenings remain popular in Cincinnati and Northern Kentucky. They originated in Catholic parishes, who used the events to raise funds and to promote a sense of community. Later, they spread to other non-profit organizations and to additional Christian denominations. The menus were mouth-watering: battered fish, tartar sauce, French fries, coleslaw, potato salad, and macaroni and cheese. Later, some fish frys added desserts, alcoholic beverages, and entertainment.

Regional restaurants even had to adapt their Lenten menus, or face losing money. The classic example is McDonald’s. In January 1959, Lou Groen opened his first Cincinnati-area McDonald’s at North Bend and West Fork Roads in Montfort Heights. However, there were two challenges. Cincinnati was a very Catholic city, and McDonald’s only offered beef on their menu at the time. And in the 1950s and early 1960s, before Vatican II, Catholics were required to abstain from meat on all Fridays of the year, as well as on some additional holy days (Matthew Plese, “Fasting Changes at the Turn of the Century,” Fatima Center, https://fatima.org/news-views/pasting-part-7-fasting-in-the-1900s-pre-vatican-ii/).

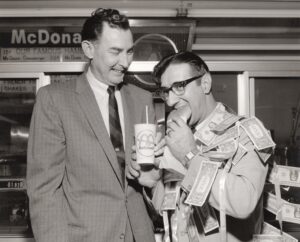

Groen realized that Catholic customers, abstaining from meat on Friday, “were bypassing his McDonald’s in favor of a nearby Frisch’s restaurant, one of the full-service drive-ins owned by Dave Frisch, the area’s Big Boy franchisee. Frisch served a popular halibut sandwich, and Groen was convinced that the business McDonald’s was losing to Frisch’s on Fridays was affecting his unit on other days as well” (John F. Love, McDonald’s: Behind the Arches. New York: Bantam Books of Random House, 1995 ed., p. 226; Paul Clark, “Filet-O-Fish Inventor Lured Patrons,” Cincinnati Enquirer, February 19, 2007, pp. A1, A11). See also this NKyTribune Rich History column.

Groen asked for permission to add fish to his McDonald’s menu but was initially denied by corporate headquarters in Chicago. Persistent, Groen “marshaled statistics on fish sales of competitors, estimated the sales he had lost for lack of a fish product and calculated the costs involved in adding one. He prepared an audiovisual slide presentation to demonstrate how a fish product could be cooked at a McDonald’s unit. He then flew to Chicago to make the pitch to McDonald’s managers and to cook for them the fish sandwich he proposed—halibut, dipped in a pancake batter, deep fried, and served on a bun.” Somewhat reluctantly, they accepted his proposal (Love, p. 226).

The rest is history. McDonald’s Filet-O-Fish sandwich was born in 1962, and the company became the “first major commercial account” of fish supplier Gorton’s. Groen’s bet had paid off, as his “average gross on Friday soared from $100 to as much as $500, and the Friday fish trade helped boost hamburger sales the rest of the week. Within two years, the volume at his once-struggling restaurant climbed 30 percent. Groen says: ‘Fish was the only thing that saved me from going broke’ ” (Love, pp. 226-227; Steven Drucker, “McDonald’s thrives despite its arch rivals,” Columbus Dispatch, March 24, 1996, p. 45)

.

Lent is not all about food, however. There are Ash Wednesday and Good Friday services. Ashes are distributed on foreheads during Ash Wednesday. On Good Friday, churches typically hold services during the hours of 12 noon-3 p.m. Also, on Good Friday pilgrims still climb the stairs to Holy Cross-Immaculata Church on Cincinnati’s lofty Mt. Adams. In 1859, when Immaculata Church was being constructed, Cincinnati Archbishop John B. Purcell raised a large wooden cross near the new church and asked people to pray for its completion. In 1860, Purcell built wooden steps to the completed church. According to James Steiner, “After the completion of Immaculata, people continued to use the wooden steps and began praying as they ascended. Good Friday became a special day of prayer on the steps but the exact beginning of the Good Friday Pilgrimage is unknown. It seems to be something that spontaneously occurred and grew. The earliest mention of the pilgrimage is found in church records from 1873, but it likely began before then” (James Steiner, Immaculata on Mt. Adams: A One-Hundrad and Fifty Year History. Cincinnati, OH: Mt. Adams Publishing, 2010, p. 126).

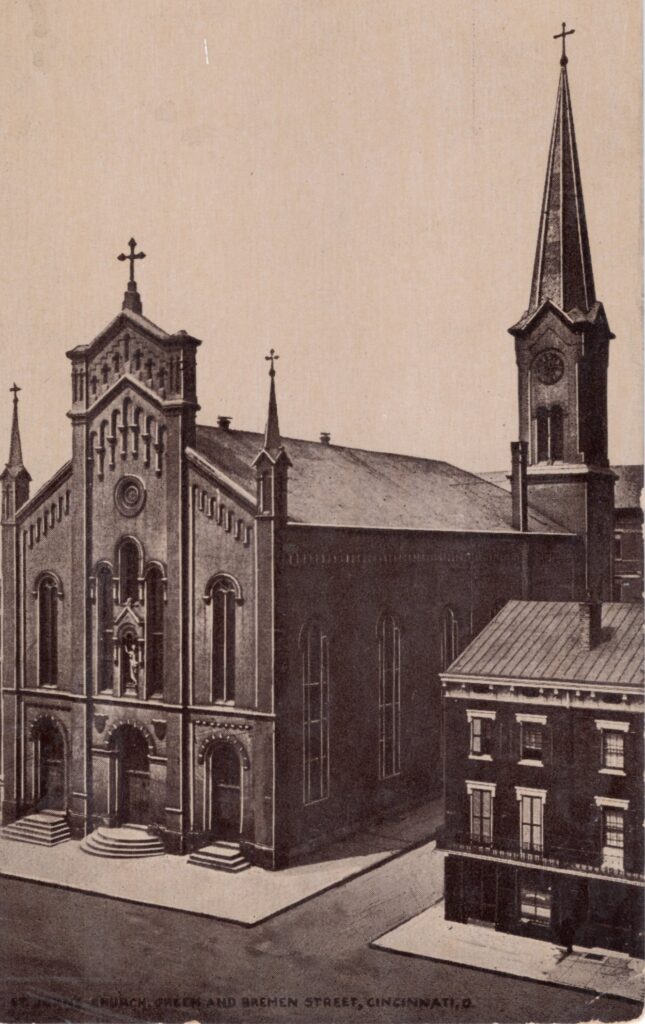

The St. John’s Passion Play is another Cincinnati-area Lenten tradition. It is heralded as the “oldest continually performed passion play” in the United States. In February 1917, during the midst of World War I, St. John the Baptist Catholic Church (St. Johannes Baptista) in Cincinnati’s Over-the-Rhine neighborhood had already experienced the loss of eight of its members to fighting abroad. The Franciscan Friars of Cincinnati staffed St. John’s Parish, and the church’s pastor, Rev. Richard Wurth, recollected the story of the town of Oberammergau in Bavaria, Germany. In 1634, the bubonic plague was raging through Europe and had reached Oberammergau with its first victims. The city’s residents vowed to hold a passion play every ten years if they would be spared further deaths. Their prayers were answered, and the Oberammergau Passion Play continues to this day (“Our Long History,” The St. John Passion Play, ).

Beginning with a play entitled Veronica, or the Holy Face in 1917, St. John Parish officially initiated the annual St. John Passion Play the following year. When the parish closed in 1969, a non-profit organization continued the production. Since then, it has been held at several locations, including St. Augustine Catholic Church in Covington, Kentucky. In 2025, the play is being hosted by Lockland Christian Church.

The popularity of passion plays in our region stems from their wide esteem in southern Germany, in predominately Catholic areas such as Bavaria and Baden. Even outside of the Lenten season, passion plays have been staged in our metropolitan area. For example, in June 1924, the Shubert Theater at 7th and Walnut Streets in Cincinnati presented “The Life of Christ.” Composed of “more than 100 Bavarian peasants,” who were “recruited from the best players who take part in Passion Plays in various parts of Bavaria annually,” the production included a “20-piece orchestra.” In fact, the Kentucky Post related that “The music is so arranged that the entire story is told without a line being spoken” (“Shubert,” Kentucky Post, June 6, 1924, p. 22).

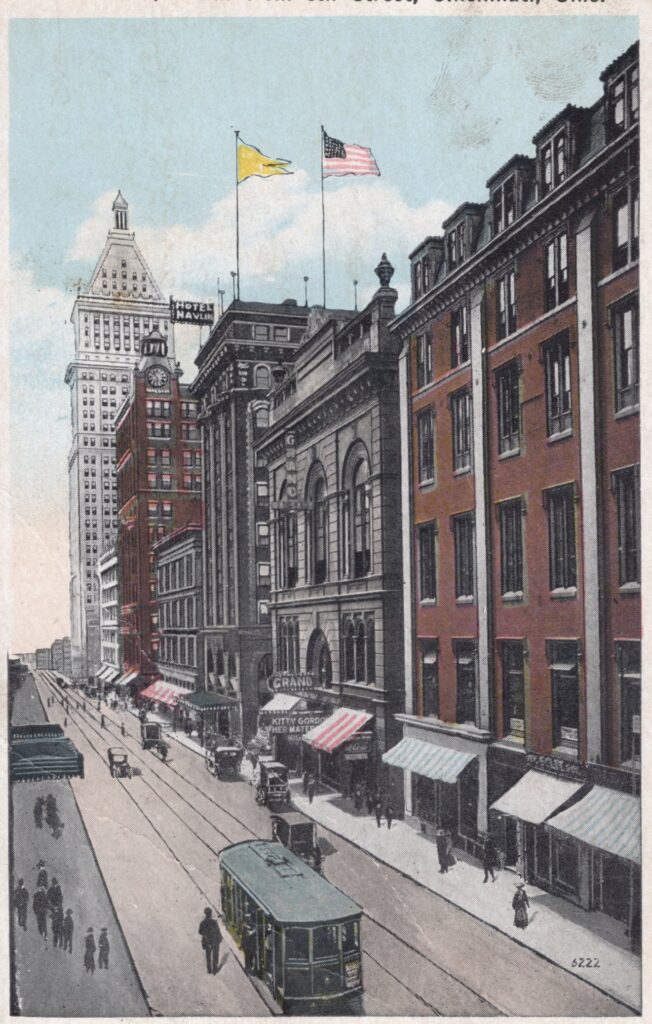

Movie studios even filmed German passion plays for audiences worldwide. In 1925, for example, the Kentucky Post noted that there were daily matinees of The Passion Play at the Grand Theater in downtown Cincinnati. The Post referred to the film as “the picturization” of a passion play “given annually by the people of Freiburg, Baden, Germany” (“Daily Matinee,” Kentucky Post, March 27, 1925, p. 30).

In March 1964, Covington Catholic High School featured its own passion play entitled The Promise Fulfilled. The cast included “68 speaking parts—52 boys and 16 girls.” Mike Hugenberg portrayed Christ, Louis Defalaise performed as Caiphas, Jim Kruer playacted Judas, and Bill Snyder was cast as Pontius Pilate. Laura Annear of Villa Madonna Academy played the part of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Rev. John McDermott, a faculty member, staged the play (Patty Mummert, “Rehearsing Passion Play ‘To Do Something Decent.’ ” Kentucky Post, March 12, 1964, p. 14).

Age-old Lenten traditions of Europe continue today in the Cincinnati and Northern Kentucky region, a reflection of its deep immigrant roots. So, whether you visit a Lenten service or eat at a fish fry, view a passion play, or pray the steps of Holy Cross-Immaculata, you’re reliving and regenerating religious traditions that have literally survived centuries of change.

Paul A. Tenkotte, PhD is Editor of the “Our Rich History” weekly series and Professor of History at Northern Kentucky University (NKU). He can be contacted at tenkottep@nku.edu. Tenkotte also serves as Director of the ORVILLE Project (Ohio River Valley Innovation Library and Learning Enrichment). For more information see https://orvillelearning.org/