By Shirlene Jensen

Special to NKyTribune

Part 23 of our series, “Resilience and Renaissance: Newport, Kentucky, 1795-2020”

Historically, African Americans of Campbell County aspired to attain an education commensurate to their basic rights of freedom. After the Civil War, the Freedman’s Bureau mandated that states provide for educating blacks. On August 1, 1866, the African-American citizens of Newport held an election and chose the following persons as trustees for a school to teach their children, and to serve for one year: Burrell Lumpkins; Beverly Lumpkins; Washington Rippleton; James Patterson; and Gus Adams. They appointed Mayor Robert B. McCrackin, a white as required by law, as treasurer (Cincinnati Daily Enquirer, August 1, 1866, p. 2).

This original Freedman’s Bureau School lasted until 1870, when the federal funding dried up. (See this Our Rich History column.)

In 1870, the Cincinnati Daily Enquirer reported that: “The colored people of this city have organized a school and employed a corps of competent teachers. The school will be held for the present in the new Methodist Church on Madison Street [now Fifth Street]” (Cincinnati Daily Enquirer, September 20, 1870, p. 7).

Newport History Museum at the Southgate Street School. (Photo by Paul A. Tenkotte, April 2020.)

That temporary school, replacing the Freedman’s school, would eventually give way to a permanent one. In 1870, the City of Newport purchased the site of what would become Southgate Street School for $1500 from Thomas and Susan Dodsworth by deed dated October 4th (Campbell County Clerk, deed book 10, p. 183). James L. Cobb’s 1939 master’s thesis, “History of the Public Schools of Newport, Kentucky” noted that, after the Civil War, “The negro was now free and a citizen of the Commonwealth” (p. 48). Schools for the black population of the state were first provided for by an act of the General Assembly of February 14, 1866, which appropriated for their schools all the taxes paid by blacks.

Other legislative acts provided a foundation for Newport to support education for African Americans. By legislative act of March 9, 1867, a poll tax for school purposes was levied on all men over 18 years of age. By an act of February 25, 1868, all fines and forfeitures paid by blacks were added to their school fund, and all money from the sale of public lands was set apart by the United States until the per capita expenditures for blacks should equal that of whites.

Beginning in 1873, the Newport Board of Education provided for African-American education. The Southgate Street School was “under the control of the same board, supervised by the same superintendent, subject to the same rules and regulations, had the same course of study and textbooks, was graded on the same standards, and was supported out of the same general fund, as were all” of the other public schools of the city (Cobb, p. 48). In order to meet the demands for the education of African Americans, the City Charter was amended as follows:

“Section 1: Be it enacted by the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Kentucky, that the Board of School Trustees of the City of Newport, out of any fund in their hand, derived by taxation under and by virtue of the city ordinances of said city be, and are hereby authorized and empowered to establish and maintain schools for the negro children of the city in such number and localities as their judgment will furnish sufficient education facilities for the colored children of the city.

Section 2: Said school shall be under the same control, rules and regulations as govern other schools of the city.”

By August 1873, the Board employed one black teacher, Elizabeth Hudson, at a salary of $35 per month. She began teaching the first Monday in September in a one-room, frame school on Southgate alley, between Saratoga Street and Washington Avenue. This marked the beginning of African-American education in Newport under the auspices of the Newport Board of Education. She served there from 1873 to 1878 (Theodore Harris, “Development and History of Southgate Street School, Newport, Ky. 1866-1955”; Newport Board of Education Minutes, 1919-1957; Annual Reports of the Public Schools of Newport 1873-1918).

In a Cincinnati Daily Enquirer report in 1874, “forty children attended the Colored School. . . . Eight of them were well advanced in practical arithmetic, and there are other indications of the usefulness of that institution.” (Cincinnati Enquirer, April 14, 1874, p. 5). F. Mackoy served as an assistant teacher in the 1878-79 year, and Dennis R Anderson as a teacher from 1879-1892.

In the 1880 census, the following students were listed in the Southgate School: Clara, Frank, and Peter Bell; Thomas and Nathan Berry; Fannie and Harry Bush; Clara Belle Davis; Henry, Fanny and Andrew Fields; Newton Joshua; Lillie Lewis; Jamie Pottum; Jamie and Dennis Rippleton; Florence Saunders; Maggie Thomas; Edward Tipton; Nannie Van Zandt; Edward and Julia Walker; and Henry Wealthy (1880 Federal Census).

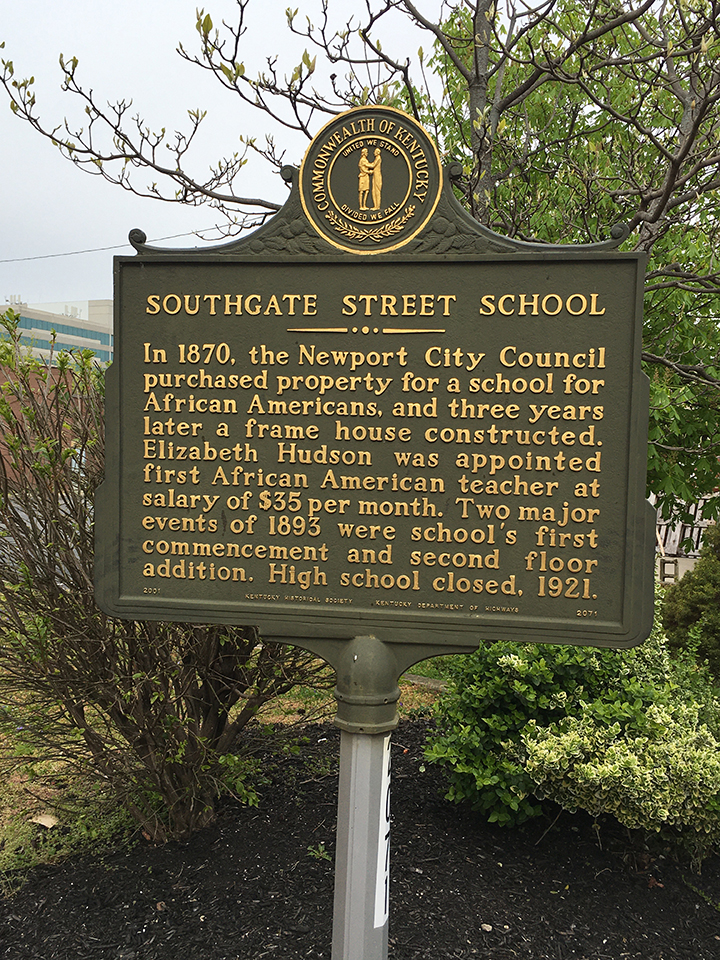

Southgate Street School historic plaque. Photo by Paul A. Tenkotte, April 2020.

In later years, enough tax had been collected to build a brick structure for the students, as well an addition to the rear. Joseph W. Lee was the principal from 1892-1898, and Zenobia Cox was an assistant teacher from 1892-1894. In 1893, the school held its first official commencement. The graduation exercise was scheduled for June 26, 1893 at the Park Avenue School Hall.

A local newspaper provided this account: “Louisa Smith and Lavinia Ellis wore white gowns and addressed the audience with essays on ‘Opportunity’ and ‘A View of Life’, which showed deep thought and careful preparation and reflected credit on the teacher, Professor Lee, as well as on the young ladies.”

Lavinia Ellis also became a teacher at the school, serving from 1900-1936. Louise A Clark served as an instructor from 1894-1912, and Louise A Troy from 1894-1904. In 1901, Southgate Street School began its three-year high school study course. Until this time, high school students had attended William Grant High School in Covington. One of the teachers was Charles D. Horner, who also served as a principal from 1898-1904. In addition, Horner was also a doctor in Newport serving the black community.

The high school classes remained very small. For example, as noted by The Kentucky Post, “The 1902 commencement exercise of the Colored High School in Newport took place Friday night at Park Avenue School Hall. There was only one graduate, Miss Elise Horner, who read an essay. The balance of the program consisted of vocal and instrumental music, reading and recitations, and was participated in by other members of the school. President George Leonard, of the Board of Education, presented the diploma” (The Kentucky Post, June 21, 1902, p. 5).

Francis M. Russell served as principal from 1904-1909. Mary Jackson was a teacher from 1906-1907, Anna Elder served as a teacher from 1907-1908, and William Spencer Blanton served as a principal from 1909-1921.

The Southgate Street School participated in many community celebrations throughout the years. For instance, a reporter noted that “In 1909, the pupils of the Southgate st. Colored Public School of Newport, will celebrate Lincoln’s century [centennial of his birth] Friday evening at the Corinthian Baptist Church.”

In 1913, racism in Newport reared its ugly head. As The Kentucky Post reported: “Considerable sensation in school circles was caused yesterday afternoon when pupils of the York, Fourth and Park Avenue Schools came home and complained to their parents that they had been required to attend a stereopticon lecture at the Park Avenue School Auditorium at which the colored pupils of the Southgate Street School were also auditors. Many parents were highly indignant because their children had been kept in the same schoolroom with colored pupils.”

The newspaper account continued: “President Frickman of the Board of School Commissioners, said last night he had not heard of the incident, but that there was a state law prohibiting the mixture of whites and colored pupils in the same schoolroom. Superintendent Sharon stated that the incident was the result of a mistake and that it would not happen again. He said the colored pupils might still be allowed to get the benefit of the stereopticon lectures but in the future they would be taken there when there are no white children present.” (Kentucky Post, February 10, 1909, p. 5).

In 1921, the Newport Board of Education decided to discontinue the African-American high school program at the Southgate Street School because of the small number of pupils enrolled. Elementary grades continued as usual. Instead, pupils were sent to the Covington, Kentucky at a rate of tuition of $50 a year for each pupil (Cincinnati Enquirer, June 8, 1921, p. 9).

Nora Ward became principal of the Southgate Street School in 1921, serving until 1940. Jessie M. Parker was a teacher from 1927-1929, Charles L. Harris was a teacher from 1932-1955 and served as principal from 1945 until the school closed in 1955. Ruth Bond was a teacher from 1936-1956.

The Southgate Street School closed in 1955, following the U.S. Supreme Court decision of Brown vs The Board of Education decided that black and white schools were inherently unequal. The students were moved to the Fourth Street School. In an interview with James A. Harris in 2019, he stated that when he moved to the new school, he learned how much the teachers at the Southgate School struggled to teach up-to-date subjects. The students rarely had any new books but were given books discarded by white schools. . .Southgate School did not have a playground or equipment, merely a parking lot. Students had to make up their own games (Interview with James A, Harris, accessible through Media Central website).

Robert Ingguls is a former student of the school He has been dedicated to the preservation of the building and its history. “We were determined this wasn’t going to be a parking lot come hell or high water because so much history is here,” Ingguls said. “It just had to be told by someone. It had to be preserved by someone.” (Cincinnati Enquirer, November 17, 2017).

Today, the building is owned by the Prince Hall Masonic Lodge 120. The museum, called the Newport History Museum at the Southgate Street School, is headed by Executive Director, Scott Clark. For more information, see this NKyTribune story.

Shirlene Jensen is currently working on a Masters in history with an emphasis on research and writing at Northern Kentucky University. She completed her undergraduate degree in history from NKU in December 2018. Shirlene has been a board member of the Campbell County Historical & Genealogical Society for fifteen years and the director of the Family History Center for fifteen years. She retired from Pipefitter’s Local 392 in 2005 after 30 years in construction.

We want to learn more about the history of your business, church, school, or organization in our region (Cincinnati and Northern Kentucky). If you would like to share your rich history with others, please contact the editor of “Our Rich History,” Paul A. Tenkotte, at tenkottep@nku.edu. Paul A. Tenkotte, PhD is Professor of History at NKU (Northern Kentucky University) and the author of many books and articles.

The Cincinnati German newspapers give an interesting insight to the dynamic of the people and politics of Newport both black and white. And we are blessed to have many of these papers physically available at the Cincinnati Public Library.

Great article. Thanks to Ms. Jensen for capturing, preserving and sharing this slice of history. So often the stories and experiences of common people, and particularly black people, are lost and never recorded in history. It is good to see that the times are changing.