“The complexity of our brain is so great that we are not simple and neither, therefore, is the task of understanding it.” — Emerson Pugh, physicist

In the ‘70’s when I was in graduate school and teaching an occasional course at the University of Cincinnati, the terms “learning style/learning modality” became popular. These over-simplified terms for explaining our brains’ various ways of processing information were usually limited to visual, auditory and tactile/kinesthetic preferences.

Visual preferences need images, writing, reading to process information most efficiently; auditory, the spoken word and discussion; tactile/kinesthetic preferences want to get hands on it, take it apart and find out how it works.

While the three aspects of processing information provided a simple introduction to the complexity of processing information, questions arose about its use in academic settings.

When I started teaching at Thomas More College in the early ‘80’s, the term was still in vogue and in various literature. The education department had a kit for simple testing to confirm learning preferences.

Would I be using the kit in classes? I needed to work with it, learn to use it first. So, I took the kit home and tested my family.

The kit had ten strips of hard black shiny plastic with stark white 1.5” tiles in four shapes: square, triangle, circle and heart; first strip had one tile, then a strip with two tiles…through a long strip with ten tiles.

The visual portion of the test had the tester display the strips one at a time for a given length of seconds. Then the person being tested would use stacks of white tiles to replicate the order. The auditory portion would have the tester, with the strip hidden, read the order at a specific pace, strip by strip, with the person replicating the order with their tiles.

For the tactile/kinesthetic portion, the person being tested would reach under a screen to feel the order on the strips, replicating the order strip by strip.

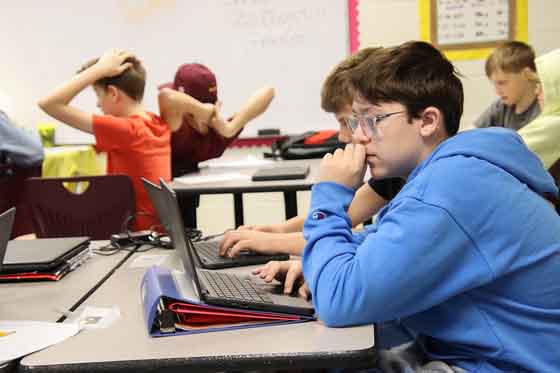

My sons in elementary and middle school both had strong balances of preferences. Neither had experienced any difficulties with learning.

Then I tested my husband. He raced through the auditory portion getting every strip perfectly and quickly through the ten strips. His tactile/kinesthetic score was good but his visual score wasn’t strong.

Time for my husband to test me. I aced the visual portion just as he had aced the auditory portion, all ten strips perfectly and quickly. My tactile/kinesthetic strength was good but my auditory score was mediocre.

Both of us had “AHA moments,” but about each other, not for ourselves.

Perhaps my low auditory score helped explain why he needed to tell me things twice unless I wrote them down. Perhaps his low visual score helped explain why post-its at eye level on the fridge didn’t get noticed by him.

When we were in college and studying together, we used my notes. He always remembered things from the lectures that weren’t in my notes. Hmmm.

So the testing kit had served a unique purpose in easing a minor frustration for each of us. He now gives me a note or a text. I make sure to tell him information. No more notes on the fridge.

With this personal experience, I did use the concept of learning styles in my courses to introduce the complexities of the brain’s learning and some of the very practical applications.

The experience also kept me more sensitive to other differences in processing information such as global approaches (overview then elements) vs. linear approaches (step-by-step from the beginning).

One of my students was struggling with a linear approach I used in a lesson so I changed my approach from linear to global when the student admitted privately to difficulty with that content. The speed with which the skill was mastered with the change was immediate and remarkable.

Visual. Auditory. Tactile-kinesthetic. Linear. Global.

Do we tend to use our own preferred means for exchange of ideas or information?

If you notice someone is struggling to learn a new concept or skill or if exchange of information seems frustrating at best, might you consider altering your approach?

Judy Harris is well established in Northern Kentucky life, as a longtime elementary and university educator. A graduate of Thomas More, she began her career there in 1980 where she played a key role in teacher education and introduced students to national and international travel experiences. She has traveled and studied extensively abroad. She enjoys retirement yet stays in daily contact with university students.