By Steve Flairty

NKyTribune columnist

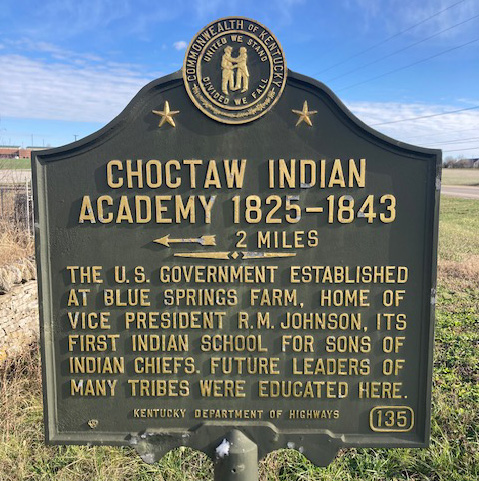

Back in the frontier days, the Choctaw Indian Academy was set up for Native American boys by the American government — and also with financial and moral support from the Choctaw tribe.

It was expected that students would perform at a high level and achieve great things for society. It was, in many respects, groundbreaking in historical perspective. Just ask Dr. William “Chip” Richardson, a Georgetown ophthalmologist, who owns the land where the school’s deteriorating school dormitory still stands.

“It was the first Federal boarding school on the request of the Natives,” he said. “The Choctaw Indian Academy was born out of treaties starting as early as 1820 where they understood that a western education was their key to survival. It was clear to the tribal chiefs that without education, they wouldn’t survive.”

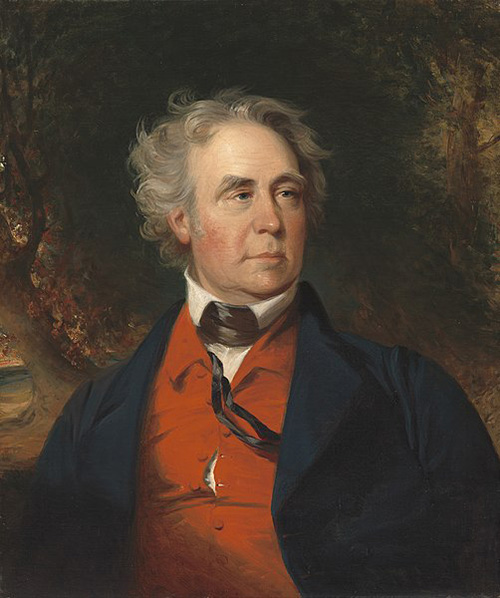

The Academy was located in rural Scott County, beginning in 1825 after it originally was started by the Baptist Mission Society in 1818, but failed for lack of finances, closing in 1821. It was established on the farm of Richard Mentor Johnson at Blue Spring (and later moved to his White Sulphur property), near Great Crossing. Johnson was a well-known national politician who spent many years in Congress and later became Vice President of the United States.

Because of its significance, the institution of the Choctaw school needs to be emphasized more aggressively in history classes, Richardson contends.

“Can you imagine a place in the frontier where eighteen different languages were being spoken?” offered Dr. Richardson. “The overwhelming story of this is actually quite progressive. The Natives were very much burned out on mission schools that were teaching trades and abusing them in the process. The school master was very much dedicated to his task of educating. They didn’t crush religion down their throats.”

Out of that place of learning came some amazing results with at least a portion of the students, especially in the early years. He noted that first Native American to be admitted to a medical school and graduate from medical school came from the Choctaw Academy. That, and the second Native American lawyer in American history graduated from the school. Each attended what was once called one of the most elite American colleges of the period, Transylvania. Richardson also referenced them becoming tribal chiefs and “doctors and lawyers in apprentice kind of form.”

For sure, the establishment of the school was not completely altruistic on the politician Johnson’s part. It benefited his family, too. An enslaved woman of mixed race, Julia Chinn, was his common law marriage partner, and their children, along with other family members, attended the school (or at least were tutored on the side by an Academy teacher). Besides the children of the Choctaw, later sixteen other tribes also became part of the Academy. Of note, research has shown that Johnson also profited financially through the school, siphoning off some of the funds.

The school started with twenty-five boys, all of the Choctaw tribe. Most were sons of high-ranking officials of the tribe, including traders. Students ranging from age six to the early twenties were enrolled. Reverend Thomas Henderson was hired as the head teacher and was charged by America’s War Department to “commence school at sunrise and finish at sundown, except on Saturday, when it would be proper to cease at noon.” The curriculum was fairly varied. Reading, writing, arithmetic, grammar, geography, practical surveying, astronomy, and vocal music were offered.

Regretfully, many challenges surfaced at the Academy during its tenure until 1848. The school didn’t work for all, especially in the later years. In her book, Great Crossings: Indians, Settlers, & Slaves in the Age of Jackson, author Christina Snyder talks in some detail about the issues.

For one thing, all instruction in the school was given in English, so with many Choctaws and other tribes that later enrolled, it was difficult to learn rapidly, with different languages spoken at various times among the students and teachers. When students arrived at the Academy, they were given two- or three-word Anglicized names, somewhat disparaging their tribal heritage. Also, Snyder points out that often the most gifted students received the greatest attention. The Academy’s support staff was largely enslaved people, an irony in respect to the mission of Choctaw Academy to advance the lives of minority peoples.

Students, generally a long way from home and sometimes bored, at times showed little discipline and got in trouble. Behavior management became unreasonably tougher, with students often being whipped. Many students, according to Snyder, felt like they were “prisoners.” Only rarely were students allowed to visit their homeland before graduating. However, a Congressional inquiry into the management of the Academy cited not enough evidence to show charges of abuse.

In time, the Choctaw Academy educational experience began to wane greatly, and largely through the efforts of former student and important Choctaw leader, Peter Pitchlynn, the school closed in 1848, with the final thirteen students being of the Chickasaw tribe.

Today, Richardson is raising funds to restore one Academy building left on his property, the dormitory, saying “the clock is ticking” on the plausibility of restoration, which he estimates will cost about $290,000 to fully do the timber and stonework to put it together. About $30,000 has been raised. A few years back, he partnered with The Choctaw Foundation to build a cover structure over the building to “save it while we figured out what we were going to do,” he said. He also noted that even though there is a temporary roof overhead, when strong winds move in a certain direction, the timbers inside still get soaked, and the building is probably within “a year or two away from collapse.”

And the fundraising status?

“The fundraising has been hard,” said Richardson. “I think there has been a lot of misunderstanding within the public in terms of the whole boarding school thing. The NPR piece that looked at abuse at boarding schools really hurt this story, in my opinion. Here we are looking at the bicentennial next year in October, (and) I’m hopeful that something big will happen.”

If interested in giving, go to the Save the Choctaw Academy page on Facebook and access the Bluegrass Community Foundation link there. The page also has lots more information about the Academy, and the Georgetown and Scott County Museum has a special exhibit designated to the school.

Thank you, Jim. Appreciate you reading my work. Sometimes I fall short, but I’m driven by the passion I feel for my state.

Steve is an outstanding writer. Goes way beyond excellent. Writing very interesting stories. History of interesting people that I would never know of without Steve’s articles.